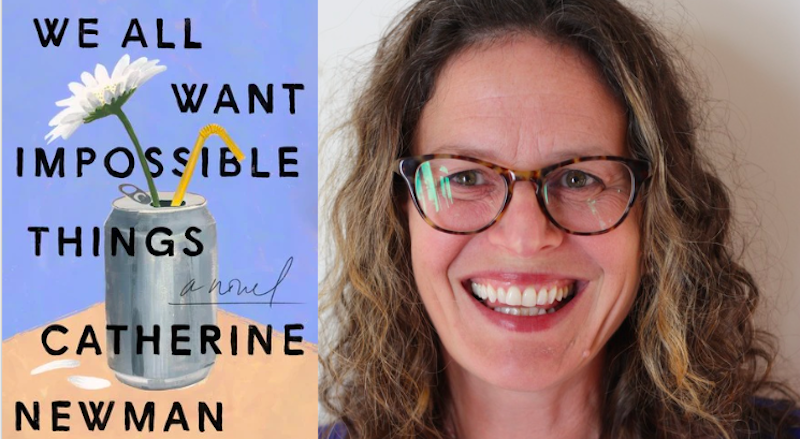

“Blown Apart by Love and Grief.” Catherine Newman in Conversation with Debra Jo Immergut

The Author of We All Want Impossible Things on Motivation, Fictionalizing Grief, and Balancing Writing While Parenting

Once upon a time, Catherine Newman and I worked together. Our day job involved dreaming up craft projects to help parents entertain their kids: Make a salad that looks like a swimming pool! Turn a toilet paper tube into a wearable Valentine!

For moms who were also breadwinners, it was an excellent way to pay the bills. But we were both secretly dreaming of publishing novels. And now we are.

Catherine’s writing has already garnered a massive readership in outlets like Real Simple and The New York Times, and in her beloved parenting memoirs and advice books (see Waiting for Birdy and How to Be a Person). But this week her debut adult novel lands. We All Want Impossible Things is fearless, open-hearted, funny, and provocative—a lot like the author herself.

To celebrate its publication, I asked Lit Hub to let me quiz Catherine about fictionalizing difficult emotional terrain, the surprising creative benefits to sweating it out in a paycheck job, and how to shift between art and commerce while also tending to mind and heart over a long-haul writing life.

*

Debra Jo Immergut: Let’s talk writing as women with families and financial responsibilities. You’ve written for years—nonfiction essays and books, a middle grade novel, and now this stunning adult novel—while also making ends meet and raising kids. How did you fit it all in? What factors made it possible—and were there times when it was impossible?

Catherine Newman: I immediately pictured trying to write on my laptop in my old house, with a toddler holding onto my knees, looking into my face, pooping. It was bedlam. Neither of my children would go to sleep in a normal way. You had to nurse them and rock them and sing some particular cycle of one million songs and then lie down with them, sneak your hair out of their sweaty little fist after they fell asleep so you could creep out. And I would lie there waiting for their limbs to go heavy, thinking, “Please let me not fall asleep. I still have a thousand words to write about making a snowman out of old socks.”

What made it possible was my partner—now my husband—Michael, who was an absolute beast of a parent and caretaker and homemaker. He stayed home with the babies and picked the kids up from school; he returned all my library books on time. He’s a massage therapist, and, as two self-employed people, we had a lot of flexibility, if not a lot of steady income.

DJI: Let’s ponder the benefits of having to balance all of these roles. Can you see ways in which your day jobs shaped you as a writer?

CN: I have always loved writing for money because, well, money, but also because it means that I’m writing all the time. It’s a great discipline for writers—needing to write on deadline. I write most days because I have to, because it’s how we eat and pay for college (kill me) and keep our cats in Fancy Feast. So that part is great, even though it sometimes feels like whoring. Even though I wouldn’t mind saying no to the marketing campaign that has to communicate that even though you had a baby and things have taken a turn for the cavernous, a tampon will still stay where you put it. These days I handle work I don’t want to do in this super passive-aggressive way–where somebody wants me to ghost-write their memoir about buying a yacht or whatever, and I’ll be like, “Sure. I charge $350 an hour. Does that work with your budget?” And either I get rich or I don’t have to do it.

DJI: We’ve laughed about some of the insane things we worked on together at a magazine called FamilyFun. The job required mad low-tech creativity: How many ways can you entertain your child with a package of uncooked spaghetti? It was a combination of the ridiculous and the sublime, and maybe it was good exercise for our artist-brains. How does it feel to look back on that work?

CN: One thing I loved about FamilyFun was that I got to write about stuff to do with little kids, while I myself had little kids who wanted to do stuff! Plus, I expensed, like, 8000 pairs of scissors and googly eyes and a terrible creative staple in those days that went by the name of “craft foam.” It was such a supportive place, too, wasn’t it? Everything good that came to me, ever, started there. All the connections and writing gigs. But I just got interviewed for an AARP story, just today, so you can tell that I am in a new chapter.

DJI: You are, and not just because AARP is showing you love—but because you’re also moving into a new genre of writing. You published some truly beloved nonfiction books centered on bringing kids into the world. Now comes your first adult novel, and it’s truly the opposite end of the spectrum—about friendship between women, and about the end of life. It bravely draws from very hard, very real experience. So how and why did you decide to go for fiction to tell this story?

CN: When my best friend died of ovarian cancer in hospice—this was almost 8 years ago now—I wrote an essay for the New York Times about it. But then I had more to say, about that friendship and her death and about hospice more generally (I’ve been volunteering in a hospice for the past 3 years), and the only way I could capture the particular experience of it—the way I was blown apart by love and grief—was fiction. I needed to fictionalize parts of it for it to be real enough on the page. Strangely.

DJI: Fiction offers a useful container for sorting out the mess that is real life. Joan Didion said that her novels captured “how it felt to me—that is closer to the truth.” Can you share a little bit about how the writing sessions felt to you, to delve into those memories years later? Did you experience any sense of catharsis, or gain any new understanding about that unimaginably difficult time?

CN: Oh! That Joan Didion quote. It’s that. I was very, very sad writing the novel. I had taken a lot of notes when my friend was in hospice and, on the one hand: What a treat, to spend that time with her again! Immersed in the things she said and thought in our last days together. But, then, I didn’t magic her back to life like I had maybe hoped to? I remember saying to my daughter Birdy, “I’m so sad.” I was kind of mystified. And she reminded me that I was spending a million hours a week actively writing my best friend to death, and that was very helpful.

The only way I could capture the particular experience of it—the way I was blown apart by love and grief—was fiction. I needed to fictionalize parts of it for it to be real enough on the page. Strangely.DJI: Life experience is one power tool you have, starting a career as novelist in your 50s, right? I’m so curious about how this feels to you. I felt like I finally got to release a bottled-up voice, but it also took all those years to work up the courage and understand what that voice needed to say. (It didn’t want to talk about craft foam, that’s for sure!) Now I see that slow build as a gift. How do you feel about being a slow-burner when it comes to publishing a work of literary fiction?

CN: Well, I do need to point out that you had already published an amazing book of literary short stories, Debra. Private Property. She’s the real deal! So you already were doing that. I think it was hard for me to switch to fiction because I was used to the constraints of nonfiction. It was like that cooking show Chopped, where they hand you a basket: “Okay, you’ve got yeast extract and a pork roast and grape Jolly Ranchers and a butternut squash. Make dinner for 6.” I felt like I had this limited palette of colors—babies, diapers, sleep, tantrums, lunch—and sure, it was kind of weird or boring, but I could always work with it. Fiction gave me a little bit of vertigo with its bottomlessness.

DJI: Too many choices. Do you remember some choices you had to make in this process—perhaps about what to fictionalize, and when to stick to the facts?

CN: I’m having a problem with pacing right now—the way that a character putting on a band-aid could be half a sentence or an entire chapter. You know what I mean? But I find that I can hear some of the story in my head. It sounds weird to say that, as if I’m channeling some kind of creative energy that’s outside of myself. But then again, our brains make up such unconventional narrative shit on their own, in our dreams, when we’re not even there to offer any guidance, so it makes some sense to think that my brain just kind of . . . generates material even when I’m not minding the shop exactly.

DJI: Who are your touchstones when it comes to fiction? Which novels are your most dog-eared? And/or in the library of Catherine’s head, where the alphabet doesn’t matter, which books are shelved next to We All Want Impossible Things?

CN: I reread your novel You Again when I was writing mine because I was trying to understand how a good story works. Narrative arc is maybe the term for it. I reread a bunch of other favorites too at that time: Miriam Toews, All My Puny Sorrows. Rufi Thorpe, The Knockout Queen. Everything Lily King, Ann Patchett. But also some genre-muddling stuff, like On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous by Ocean Vuong. Everything by Samantha Irby because I am always trying to understand humor and what makes writing funny. What do you study like scripture while you’re writing?

DJI: I get inspired by a sumptuous literary voice, because that’s something you can’t get from streaming TV. Jesmyn Ward is a favorite, and so is Edie Meidav. To learn how novels are constructed, I vivisected the first ones that first made me want to write, like Beloved and The English Patient. Even if I couldn’t put my finger on what made them so incandescent, I could map them into detailed outlines to understand their structures.

So will publishing this novel change the way you see yourself as a writer? I mean, if you need the cash, I know you’re still going to write about tampons. But a practical level, will you write the next novel first each morning, or the tampon copy?

CN: It’s funny that you ask this, because I am struggling with this issue right now. I’m about halfway through a second novel, but also I have a lot of deadlines. I have about two or three good, caffeine-fueled writing hours every day. And I find I’m doing the discretionary stuff first—the novel—because I know I’m not in danger of not doing the other stuff. But it’s very tricky and I feel like there’s an imaginary timer in my head. That line in Hamilton? “Why do you write like you’re running out of time? Write day and night like you’re running out of time?” So, no. I am definitely running out of time, but I couldn’t write at night even if you blew cocaine right up into my nostrils. What about you?

When I wrote my dissertation in the 1990s, I smoked a cigarette after every double-spaced page. Are the stickers as good as rewarding myself with lung cancer? No. But they’re pretty good.DJI: If you do need to write into the night, just call me and I’ll come over and blow some coke up your nose. And of course I still have to do money stuff!! I still write journalism, and I teach writing in a bunch of different settings, all of which I love. My gear-shifting mechanism is really cranky, so I tend to single-focus for blocks of time. When I’m really swept up in leading workshops, my own writing usually slows to a trickle.

But when I can clear time to focus on my fiction, I’ll disappear down my rabbit hole for weeks. So I’m vehemently opposed to the machismo of the “you MUST write every day” school. That never worked well for me, and it gave me a lot of guilt when I was working fulltime and mothering and writing intermittently. But I think of you as a writing pro who really knows how to shift gears and crank out the words. So can I ask… Is the second novel coming any easier? Do you feel like you’ve learned a bit from studying those models and are your muscles now warmed up after completing your first marathon?

CN: Yes, I’m totally with you. When I wrote a middle-grade novel, my goal was to write 500 words a week (really not a lot), and I finished it that way over a fairly long period of time! But this book I’m working on now… I make myself a sticker chart and it is almost embarrassingly motivating to me. I give myself a sticker for every 500 words I write in a day, and an extra sticker for every 3000 words, and boy, what I’ll do for a sticker! (Keep my butt in the chair is what, even when there are tortilla chips, say, with cheese to melt over them.) When I wrote my dissertation in the 1990s, I smoked a cigarette after every double-spaced page. Are the stickers as good as rewarding myself with lung cancer? No. But they’re pretty good. Plus, so wholesome. Which is a direction I’m trending. Or trying to.

DJI: Sticker charts! A classic FamilyFun tactic. We’ve truly come full circle.

___________________________________

We All Want Impossible Things by Catherine Newman is available now via Harper.