Black Finnegan: On William Melvin Kelley, James Joyce, and the Avant-Garde of the Subaltern

Benjamin Hale Remembers His Literary Mentor

A year after William Melvin Kelley died at the age of seventy-nine in February 2017, Kathryn Schulz published an article in The New Yorker titled “The Lost Giant of American Literature,” sub-headed: “A major Black novelist made a remarkable début. How did he disappear?” Browsing in a roadside junk shop in Maryland, Schulz happened upon a first edition of Langston Hughes’s Ask Your Mama personally inscribed by Hughes to a William Kelley. Following that breadcrumb led her to discover the author, his work, his story. I wish she had happened across that book a year earlier. It might have made Willy happy to hear himself called “the lost giant of American literature” before he died.

Willy Kelley taught for almost thirty years at Sarah Lawrence College, where I took a yearlong class from him my freshman year, and he was my faculty adviser until I graduated. I studied with and befriended other great writers and teachers there but Willy furnished me with a few of the most useful storytelling tools on my workbench and, more importantly, he infected me with a spirit, an attitude about reading and writing (and about making art in general) that I believe with religiously indefensible conviction is the right one.

*

Willy’s father worked as an editor at the Amsterdam News, the famous house organ of the Harlem Renaissance writers, and Willy grew up with Zora Neale Hurston and Langston Hughes being frequent guests at the dinner table. Willy’s family was of the mid-twentieth-century educated Black bourgeoisie that sought to ascend and transcend race—the people for whom Malcolm X reserves his most bilious vitriol in his autobiography. Although his father worked for the Harlem newspaper, the family—which included Willy’s maternal grandmother, whom Willy was close to and, Schulz mentions, was “the daughter of a slave and the granddaughter of a Confederate colonel”—lived in the Bronx in a mostly Italian working-class neighborhood. Willy attended the prestigious and nearly all-white Fieldston School, where he was student council president and captain of the track team. The promising student went from there to Harvard, where—I remember the number he told me, though I cannot vouch for its veracity given his (and my) imperfect human memory and his characteristic habit of exaggeration and embellishment—he was one of eight Black students in his freshman class.

One of Willy’s notable Harvard stories involved taking a psychology class from Timothy Leary, along with his classmate Ted Kaczynski, in which Willy and the sixteen-year-old future Unabomber voluntarily participated in Leary’s early experiments with LSD. Willy also studied alongside John Hawkes and Archibald MacLeish, and won a prize for the best writing by a Harvard undergrad, but was otherwise a terrible student, and failed almost every class except his fiction workshops. His parents died while he was at Harvard—first his mother, then his father two years later—and Willy dropped out. Schulz’s article doesn’t mention it, but I remember Willy telling me that his leaving Harvard had something to do with getting caught smoking pot. In any event, he did not graduate, and moved back to the Bronx to live with his grandmother. This was in the early sixties; around this time he started working for longtime family friend Langston Hughes as a secretary and assistant, and was close with him in the last few years of the poet’s life. He met Karen Gibson—who later changed her first name to Aiki—then a student at Sarah Lawrence, where Willy would later teach. Aiki, like Willy, came from an educated Black bourgeois family. They married in 1962, the year his first novel, A Different Drummer, was published; Willy was twenty-four and Aiki a few years younger.

Willy believed—probably rightly—that he had long ago become regarded in the publishing agora as a washed-up crackpot who wrote unreadable, unsellable fiction.

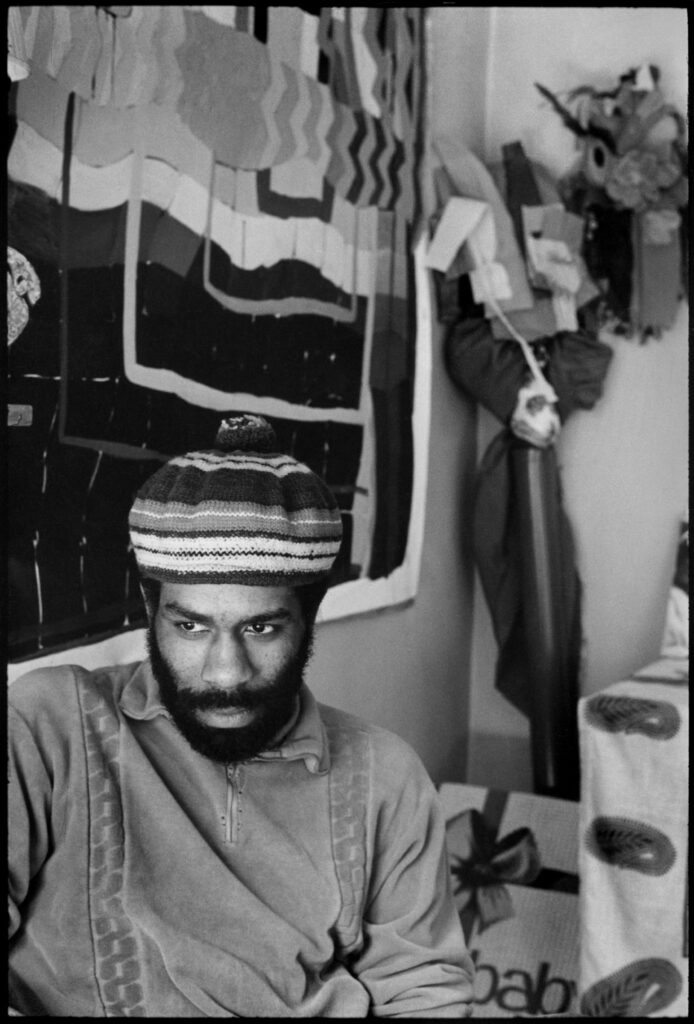

The couple briefly moved to Rome, then moved back to New York City, where their daughter, Jessica, was born in 1965. Like Josephine Baker and Richard Wright before them, the family moved to Paris in 1968—just in time for the riots—where their second daughter, Cira, was born. Willy’s best Paris stories were: (1) standing late at night on his balcony bemusedly watching irritated older Parisians fussily replacing all the cobblestones that had been gouged out of the street and thrown at cops and through windows earlier that day, fitting each one into its corresponding hole in the mortar; and (2) the time Henri Cartier-Bresson photographed him for Life magazine. Cartier-Bresson spoke little English and hadn’t read Willy’s work—it was just a job to him—but he brought along his wife, who did speak English (Willy knew some French too, but admittedly never learned it well), and the two couples went to a café and hung out for a few hours. The Cartier-Bressons were a team: the famous photographer kept silent with his camera hidden under a handkerchief in his lap while his wife drew Willy and Aiki into conversation—and when Willy got lost enough in colloquy to forget his presence, he would hear the snip-clack of the shutter and turn to see Cartier-Bresson swiftly tugging the handkerchief back over the camera. The only photograph to have survived that session Cartier-Bresson took before they left the apartment for the café. Aiki Kelley painted the large painting on the wall in the background. Willy remembered Cartier-Bresson remarking that he liked the painting, and feeling jealous of visual artists, whose work takes only a moment for the viewer to experience, as opposed to the much more time-consuming active collaboration that prose fiction requires of its readers.

Fondation Henri Cartier-Bresson / Magnum Photos. FRANCE. Paris. 1968. US novelist, William Melvin Kelley.

Fondation Henri Cartier-Bresson / Magnum Photos. FRANCE. Paris. 1968. US novelist, William Melvin Kelley.

They only lived in Paris for a year or two before moving to Jamaica, where they resided for the next decade. This long stay in Jamaica forms the fulcrum of Willy’s biography—when they went, he was a celebrated author who had famous photographers coming over to take his picture for features about him in major magazines, and when they returned to New York—the family moved to Harlem in the late seventies—he was out of money and felt forgotten. This was around the time when the giant of American literature got “lost.”

*

About the lostness of the lost giant of American literature: Willy’s writing career had been dormant for about thirty years when I met him (although he was proud that all of his five books were still in print), which would continue for another sixteen years before he died. He experienced a flash of fame in his twenties beginning with the publication of A Different Drummer. He published a story collection and three more novels in the eight years that followed. His fiction grew weirder and more difficult with each book, culminating in 1970 with his last, weirdest, and most difficult novel, Dunfords Travels Everywheres. It was published around the time the family moved from Paris to Jamaica. He wrote two more novels after that, which remain unpublished—although he occasionally published essays and short stories in magazines. He had long made peace with career burnout when I met him. He was pretty zen about it, often saying he felt far prouder of the work he and his wife had done raising their two daughters than of anything he’d written. The pride artists feel about the art they create, no matter how great, is morally tinted with childish vainglory but the pride of having been a good father is humble, private, easily had by anyone, and holier.

Willy’s mature serenity was not pure of any bitterness at the edges—how could it not have been? “It would be easier for any of you,” he told his freshman fiction workshop, “to get a book published now than it would be for me.” Willy believed—probably rightly—that he had long ago become regarded in the publishing agora as a washed-up crackpot who wrote unreadable, unsellable fiction by the aging and diminishing minority in it who remembered him.

What happened? “It’s difficult to say,” Schulz writes, “both present-day fame and posthumous reputation are elusive, mercurial, and multifactorial. Some of the downturn in Kelley’s fortunes likely had to do with the changing political climate…as the momentum of the civil-rights movement ebbed, those with the power to make publishing decisions turned their attention elsewhere.” There’s almost certainly truth in that. A boom of interest in Black authors during the turbulent head rush of the sixties declined as the revolution fell out of vogue. But I think the fading of Willy’s earthly star after 1970 had more to do with a cultural shift in aesthetics.

A Different Drummer is strange in its content but as for form, the sentences are transparent and accessible. His next book, Dancers on the Shore, his only collection of short fiction—most of which I think was probably written before A Different Drummer— contains several fantastic short stories and a few duds, none outrageous either in form or content—i.e., not veering too far from (and I so dislike this word I write it with my nose pinched) “realism”—or in sentences that want to do more than communicate meaning well and without aggressively visible beauty. His next book, A Drop of Patience, narrated by a blind jazz musician, was a formal experiment: to write a novel with no visual information. (I often urge my students to remember their other four senses; we tend to lean too heavily on our eyes; cutting sight out of prose fiction is just as difficult an obstruction as writing without the letter e—and, in my opinion, a more interesting one.) One might think it a wilder gambit for a sighted Black man to write from the perspective of a blind Black man than that of a white man who can see, but not—judging by some critics’ reactions to his fourth book, his third novel, dem—a mediocre white man about as tormented and pathetic as his approximate contemporary Alexander Portnoy, whose wife has an affair with a Black man and, in an astronomically rare but not impossible case of hetero-paternal superfecundation, gives birth to Black and white twins. Mitchell Pierce goes on a quest to find his cuckolder and make him adopt the dark-skinned baby, journeying through the underworld of Harlem with a headful of the agonies and anxieties about Black people that a white man might have had in 1967. With this book, Willy’s style began venturing into aberrant linguistic territory.

Some writers want you to look through their words like a clear window that gazes onto the story, and some writers want you to see the story through the window, but also pay attention to the words themselves—to look at the window. Willy was heading in the latter direction. There’s a footnote in Zadie Smith’s essay “Rereading Barthes and Nabokov” in which she describes this continuum:

[T]here is a style that believes writing should mimic the quick pace, the ease, and the fluidity of reading (or even of speech). And then there is a style that believes reading should mimic the obstruction and slow struggle of writing. Raymond Carver would be on that first axis. Nabokov is way out on the second. Joyce is even further

Willy’s final book, Dunfords Travels Everywheres, published three years later—hallucinatory in content and tilting at insanity in form—is best understood as an homage to James Joyce.

*

It is not possible to overstate how important Joyce was to Willy. On the first day of class, a student asked an understandably practical and banal question about the professor’s grading policy. Willy put on the grave senatorial face and voice he assumed to make utterly ridiculous pronouncements and said, “Shakespeare would get an A-plus in this class. Joyce would get an A. I would get an A-minus. The best you can hope for is a B-plus.” (In actuality, Willy had the same aristocratically aloof contempt for the piddling concern of letter grades as I do. I think he gave us all As.)

Shakespeare lives in the sky, whereas Joyce was his prophet on earth who Willy spent a lot more time reading and thinking about. (Note: Willy had been an actor, and of course he had played the one great Shakespearean role then available to a Black man, Othello. The title of his novel A Drop of Patience is a quote from Othello. Shelve for later.) When I came to college in 2001, I had for several months been part of an informal fanatical two-person Joyce reading group with one of my best friends then and still, Andres Restrepo. Joyce progressed, like Willy would, from a more or less accessible style to weirder and weirder and more and more difficult; most Joyceans begin the ascent chronologically in the foothills of Dubliners and climb on to A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man before attempting Everest: Ulysses; most people—even proud Joyce freaks like me, Andres, and Nabokov—stop there, but those who want to can attempt the shorter mountain but the harder climb, Finnegans Wake—which, also like K2, is there. (This pair of Nabokov’s remarks on Joyce limns the difference between the two magnum opera: “Ulysses, of course, is a divine work of art and will live on despite the academic nonentities who turn it into a collection of symbols or Greek myths….Oh, yes, let people compare me to Joyce by all means, but my English is patball to Joyce’s champion game”; on Finnegans Wake: “…a persistent snore in the next room.”) I read Dubliners and Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man in my senior year of high school while Andres, in his freshman year of college, had read Ulysses and already started up the road with Finnegans Wake. (Andres’s AOL chat handle then was “Gaggin Fishygods!”—a phrase that appears in FW.) The summer after I graduated, in the moments of downtime working at a custom picture-framing franchise in a mall, I sat in a room full of bad art at the checkout counter with Ulysses and Don Gifford and Robert J. Seidman’s Ulysses Annotated: Notes for James Joyce’s Ulysses winged open side by side, crawling through the text while pausing frequently to consult Gifford and Seidman, hunting down every reference I didn’t understand, making copious notes in the margins of the novel. I got through the first three chapters that way (Stephen Dedalus’s section) and about half of the fourth—the first chapter of the middle section, Leopold Bloom’s (mostly).When I arrived at Sarah Lawrence, I was pleased to learn the only required text for William Melvin Kelley’s first-year fiction workshop was Ulysses. I thought I had a significant head start on the course reading, but no: Willy told us to start with the fourth chapter. Read the first three if you want, he told us, but the stuff he wanted to talk about begins with Calypso. (Joyce scholars nickname the twenty-four chapters after their corresponding books in the Odyssey, which Nabokov hated: “I once gave a student a C-minus, or perhaps a D-plus, just for applying to its chapters the titles borrowed from Homer while not even noticing the comings and goings of the man in the brown mackintosh.” Willy also scorned them.)

Mr Leopold Bloom ate with relish the inner organs of beasts and fowls. He liked thick giblet soup, nutty gizzards, a stuffed roast heart, liver slices fried with crustcrumbs, fried hencod’s roes. Most of all he liked grilled mutton kidneys which gave to his palate a fine tang of faintly scented urine.

In one of my first conferences with Willy, I told him I had already been reading Ulysses over the summer, and eagerly showed him my copy of the book, the first three and a half chapters of which looked—still look—like a medieval palimpsest of my own harebrained adolescent shit scribbled around the text, crowded into every available space of white. Willy was unimpressed.

“You’re reading it all wrong,” he said. The way you’re reading it (I’m paraphrasing), you might learn every little reference to Greek mythology or whatever, but you’re not listening to the music of the language, which is the most important thing about Joyce. The first time you read it, ask yourself, What is going on in the concrete reality around the characters? That is to say, just read it like you would read anything else. After that, I put down the pen, left my copy of Gifford and Seidman’s Ulysses Annotated on the shelf, and simply read it. Sure enough, the music started playing in my mind. I wasn’t “climbing” anymore, which is a lame metaphor anyway. I was dancing—moving for fun—and not with the pitiful telos of becoming a person smart enough to have read Ulysses. That is, I was reading for pleasure.

*

Dunfords Travels Everywheres begins with an epigraph, a quote from Portrait of the Artist (Willy removed parts of it, chopped it up with line breaks, and put it in italics):

The language in which we are speaking

is his before it is mine…

I cannot speak or write these words

without unrest of spirit.

His language, so familiar and so foreign,

will always be for me an acquired speech…

My soul frets in the shadow of his language.

Willy often said that Black American literature shares a spiritual kinship with Irish literature. A Black man born in the New World speaks the native language he speaks because it was forced upon his ancestors, and the same is true of an Irishman. (This was truer in the early twentieth century than today, after a hundred years of Irish independence and the deliberate revival of the Irish language.) I gave this opinion to a character in the novel I began soon after taking his class and finished only a few years ago. One of the main characters, a white American ethnomusicologist conducting field research in the Caribbean, befriends islander Hugo Campbell, a Black man of radical political leanings she eagerly shares. Perusing his bookshelf, she sees books by Frantz Fanon, Aimé Césaire, and C. L. R. James, but also Joyce and Yeats. The Irish writers seem incongruous in that company to her, but Hugo says:

Everything the English did to African people in the New World, and later to African people in Africa itself, they did to Ireland first. You can’t speak your language, you can’t play your music, you can’t practice your religion. Your land is our land, now. You belong to us. And both the Irish and the Africans were left to make art with the tools the English forced upon them—their instruments, their gods, their language. And they had to make it in secret, and from the inside out. Irish and Black American art share the same impulse of subversion, the same sense of play.

This is pretty much a quote from Willy, somewhat degraded by my memory and made more serious sounding by the character. A long time later, I would encounter the same thought in Edward Said’s Culture and Imperialism, in which he argues we should consider the Irish writers of Joyce’s and Yeats’s generation the first postcolonial writers. From a subchapter titled “Yeats and Decolonization”:

From this perspective Yeats is a poet who belongs in a tradition not usually considered his, that of the colonial world ruled by European imperialism during a climactic insurrectionary stage. If this is not a customary way of interpreting Yeats, then we need to say that he also belongs naturally to the cultural domain, his by virtue of Ireland’s colonial status, which it shares with a host of non-European regions: cultural dependency and antagonism together.

Put more poetically: “My soul frets in the shadow of his language.” An important aspect of the kinship between Irish and Black American culture is the spirit of subversion and play that arises because of this simultaneous dependence and antagonism. Black people in the Americas had nothing to make music with but European instruments, but they played them in strange, off-kilter ways they had never been played before, and blues, jazz, and rock ’n’ roll came out of them. And like the Irish, Black American writers had nothing to make literature with but the language their progenitors had been forced to speak, that colonized their minds before they were born, the European words they understood, spoke, and thought in. The oppressor is inside your own mind. But the subaltern can subvert the master’s language by twisting it and playing with it, being irreverent with (and toward) it. Taking pleasure—joy—in running the English language outside the prescribed lines on the playing field, fucking around with it in funny, clever ways, is an underhand act of political rebellion. It says: Your language is not sacred to me. I can change it. I can make it my own. I can write “Bababadalgharaghtakamminarronnkonnbronntonnerronntuoonnthunntrovarrhounawnskawntoohoohoordenenthurnuk!” on the first page of Finnegans Wake.

*

This brings me to another reason why Willy’s name has been invoked somewhat more frequently in the last decade: he was the first person in history to commit to print the word “woke,” in the headline of his 1962 New York Times op-ed, If You’re Woke You Dig It: No mickey mouse can be expected to follow today’s Negro idiom without a hip assist. (He surely didn’t write that subhead— it doesn’t sound like him—though he probably contributed the “mickey mouse.”) In 2021, Riverrun, an imprint of Quercus Books, reissued new paperbacks of Willy’s books with redesigned covers, and with this fact about the word “woke” injected into his bio. The op-ed begins with a sign in a subway car that Willy saw with the sentence “This is your train, take care of it” translated into “twenty-one real or fancied languages.” One of them read, “‘Hey cats this is your swinging-wheels, so dig it and keep it boss.’ They called that—Beatnik.” In the fifties Black American vernacular— particularly jazz slang—transmitted outward from Greenwich Village by the hippest white people, began to osmose into mainstream culture, and when it appears in something as square as a public service message from the Transit Authority, you know it’s dead. “To [Black people], the words and phrases borrowed from them by beatniks or other white Americans are hopelessly out of date. By the time these terms get into the mainstream, new ones have already appeared, although some (such as to dig or cool) remain staples of the idiom despite wide non-Negro use. A few Negroes guard the idiom so fervently they will consciously invent a new term as soon as they hear the existing one coming from a white’s lips.” This article was not such a significant event in Willy’s life—it was a tie-in ad for A Different Drummer, published that month. But it’s seeded with his lifelong obsession: the subversion and play of language.

Shakespeare lives in the sky, whereas Joyce was his prophet on earth who Willy spent a lot more time reading and thinking about.

The word “woke” appears exactly once in his story collection Dancers on the Shore (a hapax legomenon), spoken by the morally ambivalent trickster-god in his pantheon of characters, Carlyle Bedlow, who narrates the story “The Most Beautiful Legs in the World.” Bedlow goes through a battery of bizarre manipulations trying to prevent his friend Hondo from marrying his girlfriend, an otherwise beautiful woman with one deformed arm, because he erroneously believes her deformity is heritable:

We were getting down to the nitty-gritty now. Whatever I did, both of them’d be watching me and I had to be careful. I had to make sure Hondo was woke that I was doing all this for his own good.

Here the word essentially means “understanding” or “knowing,” without any overt political cast to it at all. In the political sense, the word briefly surged in earnest usage on the left around the time of Trump’s first theatrical descendance down the gaudy golden escalator, and was added to the OED in 2017 (Merriam-Webster’s current definition is “aware of and actively attentive to important societal facts and issues (especially issues of racial and social justice)”) but by then it had already become something conservatives use to mock liberals. Social media has exponentially accelerated the birth-life-death cycle of new slang; at the end of this cycle most neologisms either melt into the language with bland neutrality (hip, cool) or become linguistic artifacts that signify their times (dig, groovy), but after “woke” died, it immediately rose from the grave in its zombie form as a weapon. Willy was such a keen observer of the ways culture transmogrifies the meaning of language that it’s a shame he missed most of the journey through heaven and hell “woke” has been on since his death in February 2017—I think it probably would have amused him.

*

I learned just one new thing about Willy from Schulz’s article—that, in Jamaica, he apparently converted to Judaism:

This came about because Kelley started smoking ganja with some locals behind a neighborhood chicken joint, and every day before they lit up they read aloud from the Bible….[Willy and Aiki] were searching for moral guidelines to help them raise their children, and they soon found what they wanted in the Pentateuch. One by one, they began shedding old traditions—bacon, Christmas, Sunday Sabbath—and adding new ones: Shabbat, Yom Kippur, a kosher kitchen.

Although I didn’t know this, it is characteristic of Willy that smoking weed behind a chicken joint somehow led to his converting to Judaism. Willy talked about Rastafarianism more often than Judaism—but the two are closely connected. The story of the Jews escaping Egyptian slavery is important to the art that Black people in the New World would make—another instance of taking something that was forced upon them, the Bible, and making it their own. Examples abound: Go Down, Moses; Bob Marley’s Exodus; Desmond Dekker’s “Israelites.” The Torah reverberates in mystical echoes down the halls of Black America (all the Americas): in Southern spirituals, Marcus Garvey, Rastafarianism. Willy liked to point out that a dreadlocked Rasta is simply what happens when a Black man follows the same grooming and sartorial codes Yahweh lays down for the Jews in Leviticus.

When Judaism did come up, Willy would of course inevitably mention Leopold Bloom, the bumbling, cuckolded, put-upon, middle-aged everyman of Ulysses, the half Jew who first thinks about his Levantine heritage when he sees an ad seeking investors for “Orangegroves and immense melonfields north of Jaffa”:

The oldest people. Wandered far away over all the earth, captivity to captivity, multiplying, dying, being born everywhere. It lay there now. Now it could bear no more. Dead: an old woman’s: the grey sunken cunt of the world.

Desolation.

The story of the Wandering Jew lurks and floats through Bloom’s thoughts: diaspora. In the most famous episode of Ulysses having directly to do with Bloom’s Jewishness, set in Barney Kiernan’s pub in the twelfth chapter, he battles the cyclops: the one-eyed Irish nationalist, staunch Fenian, and anti-Semite, obsessed with politics, surrounded by newspapers, called only “the citizen,” in whose eye Bloom could never count as a true Irishman:

—Saint Patrick would want to land again at Ballykinlar and convert us, says the citizen, after allowing things like that to contaminate our shores.

Bloom’s bravest moment of June 16, 1904, comes a few pages later:

—Mendelssohn was a jew and Karl Marx and Mercadante and Spinoza. And the Saviour was a jew and his father was a jew. Your God.

—He had no father, says Martin. That’ll do now. Drive ahead.

—Whose God? says the citizen.

—Well, his uncle was a jew, says he. Your God was a jew. Christ was a jew like me. Gob, the citizen made a plunge back into the shop.

—By Jesus, says he, I’ll brain that bloody jewman for using the holy name. By Jesus, I’ll crucify him so I will. Give us that biscuitbox here.

Willy appreciated the complexity and nuance with which Joyce saw his home country at the dawn of its independence. His soul fretted in the shadow of his oppressor’s language, but the fiercely patriotic Irish nationalist—the citizen—is no hero either. The citizen’s anticolonial mindset is romantically stupid, poisoned with racist, jingoistic mythology.

In the ninth chapter—Stephen Dedalus and his friends in Dublin’s National Library, splashing about in effervescent persiflage about Shakespeare—a character says to him, “Our national epic has yet to be written”: Joyce winking at the reader over the heads of his characters. In writing that national epic, and making his Irish Odysseus half-Jewish, Joyce anticipates and rebukes the expectations of people like the citizen. True, there are not a lot of Jews in Ireland— but there are some, and a notion of Irish “purity” that excludes them reeks as thick and idiotic with auto-hagiographic mythmakery as those statues of Confederate generals erected across the American South in the early twentieth century. And this acknowledgment of nuance, complexity, and ambiguity in the politics of identity is without a doubt another thing Willy shared with Joyce. He was not someone who thought in simplistic terms of good and evil. One of Willy’s favorite things to do to his characters was to leave them in a conflicted, confused, ambivalent moral impasse about race.

This happens a few times in Dancers on the Shore. In the story “What Shall We Do with a Drunken Sailor?” Peter Dunford—a straitlaced, responsible character—meets a vulgar, sleazy, white man, a merchant marine on a one-night shore leave in Boston, who asks to be directed to a whorehouse:

“See? I got about seventy dollars. I’d pay it all if I could find that girl…honey-colored…brown eyes…with long legs like a dancer…and class. But you’re colored yourself. I guess you know colored girls are best.” He poked Peter in the ribs.

“Let me ask you one question.” Peter began slowly, calmly. “Do you think every Negro in the whole world is a God-damn pimp?”

After that flare-up, the sailor offers to buy Peter a drink to apologize for offending him:

Peter almost refused again, but then got an idea. He would gain the sailor’s confidence, would pretend he knew of a whorehouse, and would send the sailor to the suburbs on a wild, fruitless chase. He smiled. “All right.”

Over drinks in a bar, the sailor talks wistfully about the girlfriend he supported for ten years, whom he would see between voyages for a few weeks at a time in their cottage in New Jersey. In the end, she abandons him, leaving a note on the door telling him she’s moved to Las Vegas. At the end of it, he mentions that when he met her she was dancing at the Cotton Club, and “Peter choked on his drink.” (He realizes the girlfriend the sailor’s been talking about was Black.) Peter goes through with his plan, giving him directions to Waltham, knowing it will take him all night to get there and he’ll find only a boring far-flung suburb that definitely has no whorehouses in it. They’re about to part ways but then Peter “was thinking of the Cotton Club girl in the Las Vegas hotel. He saw the sailor coming home and finding her note.” Peter tells him he just remembered that the whorehouse in Waltham is closed that day. It doesn’t say what exactly Peter thought—something about the fact that the sailor’s girlfriend had been a Black woman, something slightly humanizing about his heartbreak—but it makes him decide not to punish him by making him waste his time, and simply leaves him as he found him, wandering down the street. “He was going in the same direction as when he had first stopped Peter. He probably still did not know where he was.” The sailor doesn’t really redeem himself, and Peter’s initial hatred of him has only been transformed into indifference. The story ends with an awkward flatness, a deliberate absence of resolution. A story that begins making the reader think it is saying something ends by refusing to say anything.

In “A Good Long Sidewalk,” Carlyle Bedlow as a young teenager trudges around the Bronx after a blizzard, shoveling walks for money. At one house, he meets Elizabeth Reuben, “a small, plumpish white woman of about forty in a pale blue dress. She was not exactly what he would have called pretty, but she was by no means a hag.” There is also a Mr. Reuben on the plate by the doorbell, but his name is crossed out. She insists he come inside and drink a cup of hot chocolate. Warily, Carlyle sits at her kitchen table and sips the hot chocolate, scanning for whatever she’s trying to pull on him. The child Carlyle doesn’t quite see it, but the reader sees that Elizabeth Reuben is in a bad way—miserable, unhinged with heartbreak. She insists on extravagantly overpaying him, then flings herself at him, hugging and kissing him; he pushes her away; she confuses him by insisting he still take the five dollars for shoveling the walk, and hurries him out the door. Carlyle shovels her walk and goes home, and the next day learns that Elizabeth Reuben committed suicide by leaving the gas on the night before. The story ends around the dinner table—and like the other story, ends flatly, openly, leaving the reader morally and emotionally confused:

Carlyle looked at his mother. “Are white people all bad? There’s some good ones, ain’t there, Mama?”

“Of course, Junior.” His mother smiled. “What made you think—”

“Sure, there is, Junior.” His father was smiling too. “The dead ones is good.”

*

Willy maintained for many years the meditative habit of daily scripture reading he had begun in Jamaica. He told me that every day he read a page of the Bible and a page of Mao’s Little Red Book.

The latter disturbed me—I thought it a quirky vestige of the foolishness with which leftists in the West in the mid-twentieth century romanticized the Soviet Union and China a wide, safe distance away from these places and without firsthand experience of them—more excusable in the 1930s than in the year 2001. (I agree with John Lennon: “But if you go carrying pictures of Chairman Mao / You ain’t gonna make it with anyone anyhow.”) Willy’s thing for Mao was closely linked to his earnest feminism. Willy’s feminism wasn’t flimsy and performative—it was a fraught struggle between his life as a man—particularly a straight Black man who grew up in honor-culture, working-class Bronx in the 1940s—and his deep and genuine love for and pride in his wife and daughters. (Once, Willy decoded his runic signature for us on the chalkboard:

It’s a W and an M transposed atop each other, which also forms the arm and the leg of the K; the vertical lines drawn through the first three points of intersection represent his wife and two daughters, and the last one is the spine of the K.

Mao’s feminism. There was something short and simple Willy quoted all the time about women and the revolution, and I can’t remember it exactly. I went looking for it in the chapter titled “Women” in the Little Red Book and couldn’t find it but the chapter is full of things like this:

In order to build a great socialist society it is of the utmost importance to arouse the broad masses of women to join in productive activity. Men and women must receive equal pay for equal work in production. Genuine equality between the sexes can only be realized in the process of the socialist transformation of society as a whole.

Talking with Willy in his office, I voiced my uneasiness with his admiration for Mao and pointed out that through the Great Leap Forward, Mao was responsible for significantly more deaths than Hitler and Stalin combined. Willy shrugged, said, “Well…” and shuffled through a sheepish apologia for Mao awhile before concluding, “And also—we’re talking about China, here, man—forty million’s just a drop in the bucket!”

We laughed the disagreement away, and he was therewith done for the day talking about Mao.

About his other daily reading, the Bible: one day Willy came to class already wearing the grave senatorial face that always presaged a joke, sat down heavily, pulled a Bible from his book bag, and slapped it on the table, announced to everyone he was going to read us a Bible story, peeled it open to a dog-eared page, and solemnly read to us a passage from 2 Kings about Ben-Hadad laying siege to Samaria, resulting in a famine so great that a donkey’s head sold for eighty shekels of silver. A woman approaches Jehoram, king of Israel, as he walks along the ramparts of the city wall, crying out to him for help. “The king asked her, ‘What is your complaint?’ She answered, ‘This woman said to me, “Give up your son; we will eat him today, and we will eat my son tomorrow.” So we cooked my son and ate him. The next day I said to her, “Give up your son and we will eat him.” But she has hidden her son.’”

Willy found this really funny.

“She sounds so whiny,” he said. “We will eat him today, and we will eat my son tomorrow…”

*

On the first day of class, Willy walked around the seminar table and handed each of us the gift of a wide-ruled black-and-white-marbled Composition Book. He told us we were to write our assignments—by hand, of course—in these notebooks. For the remainder of the year, we were to bring to class two things: our Composition Books and Ulysses.

A few weeks later, with Willy in his office, he asked me to read him something I’d written. I pulled out my own non-official-issue notebook—spiral bound at the top—and Willy jumped, boomed with anger: “WHY AREN’T YOU USING YOUR NOTEBOOK!”

Willy didn’t worship literature—he simply loved it. And the way he thought about writing fiction was startlingly concrete.

Chastened, frightened, I told him. I like to write with a fountain pen. The thick, smooth, bleedy, effortless ink flow—no other writing utensil has it beat for visual and tactile satisfaction. But it needs a flat surface. I like spiral-bound notebooks because they lie flat on the table and are bound on top so that when I’m typing it up later, I can prop the notebook on a music stand and easily flip the pages over without having to take it off the stand (they have to be spiral bound so that the pages don’t flop back over the top while I’m typing). I don’t like writing in those classic stitch-bound, marbled Composition Books because I don’t like the way the pages curl toward the edges of the binding. That curl makes the nib of a fountain pen dry and scratchy. That was my explanation.

The anger—mostly mock anger, anyway—left Willy’s face, replaced by the same easygoing grin with which he’d excused on grounds of statistical relativity the atrocities of Chairman Mao Zedong. He waved his hand, sweeping the issue out the door.

“OK,” he said. “You are a writer.” It was fine with him that I had jettisoned his present as long as I had some finicky, neurotic reason for it. In a nebbish voice, hand gently pantomiming a curling page, he said: “I—I don’t like the way the page curls…” Then he sat back and pronounced his Solomonic final judgment on the matter: “You can use your own notebook.”

*

As I mentioned, Willy had acted at Harvard, and studied the craft seriously. In the late fifties and early sixties the Method was the rage, especially among the young actors of about Willy’s age, who all idolized Marlon Brando and would go on to transform American cinema in a few years: Warren Beatty, Al Pacino, Dustin Hoffman, and so on. Marlon Brando had studied with Stella Adler, who had gone to the USSR in the thirties to study with the great man himself, Konstantin Stanislavski. Adler tweaked the Stanislavski Method a little, and Brando brought it to Hollywood.

Willy met Marlon Brando once, at a party in James Baldwin’s apartment. Brando’s career had been waning for several years when Willy met him. Brando would later say in interviews that he withdrew from Hollywood because of his disgust with the film industry but in truth it also had to do with the film industry’s disgust with him. The mess he made filming One-Eyed Jacks and his mutinous takeover of Mutiny on the Bounty, which caused the production to balloon ten million dollars over budget, gave him a reputation as a troublemaker, a prima donna, a liability. His next five movies were flops. When Willy met him he had just finished filming A Countess from Hong Kong, a romantic comedy costarring Sophia Loren and directed by a nearly eighty-year-old Charlie Chaplin (it would be his last film), and spoke of the experience with venom and bitterness. Chaplin was an asshole, Loren was an idiot, the film was shit, and Brando was depressed. In five years The Godfather would launch him into a rare second act of American fame, but at the time it seemed the curtain was closing on him. Also, he and James Baldwin were living together as a couple. Their relationship wasn’t an open secret—it wasn’t even a secret. Willy said they would often walk down the street in Greenwich Village holding hands. Willy was at that party because he was friends with Baldwin. Willy had his daughter Jesi with him. This would have been in 1966 or 1967, and Jesi would have been about a year and a half old. Everyone at this party was too intimidated to talk to Marlon Brando, and so he awkwardly floated around alone, eventually parked himself in a chair beside a table of hors d’oeuvres, and just sat there compulsively snacking in bored solitude. Willy, with his toddler daughter, sat down next to him and spent the night talking with him, and Brando was grateful for his company. They talked about acting, they talked about writing, they talked about art. Brando kept gingerly touching Willy’s daughter’s hand and, marveling at the sheer smallness of children, saying, “Such small hands…such small hands…”

Willy liked to say—and I say it now to my writing students—that if ever there were a sister art to writing fiction, it would be acting: both arts are about trying to get inside the heads of made-up people. Both arts involve trying to imagine the experience of someone who isn’t you. Willy said a fiction writer would do well to study the Method.

In 1994 Larry King conducted an unintentionally hilarious interview with a colossal, late-stage Marlon Brando. A few minutes in, there’s this exchange:

LK: OK, help me with something, because it’s fascinating. Let’s say you get a role, it’s The Godfather.

MB: Yeah?

LK: You’re not a Mafia kingpin.

MB: Yes I am. So are you.

LK: No, no, you’re not a Mafia kingpin.

MB: …Well, as a matter of fact, I am not.

LK: OK—

MB: But we are—there isn’t anything that you are, or that you feel, or that you have—that I don’t feel—or that I don’t have.

There it is—the faith at the heart of the Method and also of writing fiction. It is a faith: untestable, unfalsifiable, perhaps untrue. But it’s a faith one must have in order to play a character convincingly or to write one.

Fiction itself is an experiment in trying to experience the experience of another. Like the faith Marlon Brando expressed to Larry King that anyone can imagine the experience of anyone else, it is impossible to prove. But we can try—we can imagine. The mystical mise en abyme of this humdrum and impossible metaphysical backflip—imagining someone else’s experience of a world far more bizarre than hobbits and orcs and elves, much more out-there than intergalactic wars on other planets millions of years in the future—is simply writing a character’s thoughts in a third-person work of fiction.

Which brings us back—as most things with Willy eventually returned—to James Joyce: one of the greatest explorers of other people’s minds, inhabiters of alien consciousness, in literature—one of the things, along with his musicality, that Willy most loved about his fiction. “Only Joyce could let us get so close to a character,” Willy said. “We’re with him when he jerks off, we’re with him when he takes a shit!”

*

Willy had the autodidact’s tic of not knowing—or not caring about—the fancy lit-crit terms for things. Something I would later learn there definitely exists a fancy lit-crit term for—free indirect discourse—Willy called “Joyce Voice.” Here’s one of Willy’s writing assignments, which I have adopted, slightly modified, and now give to my students:

Write a 27-sentence story of 9 paragraphs of 3 sentences each, the first sentence of each paragraph in the third-person past tense, and the second and third sentences in the first-person present tense.

This assignment is a tutorial in writing Joyce Voice. It’s an exercise in moving in and out of a character’s mind, weaving between the realm of action—the concrete physical universe around a character—and the realm of consciousness. Its ease in moving between exterior and interior is prose fiction’s quiet superpower.

In a visual narrative medium (a play, a film, a TV show) everything a character thinks, feels, believes, remembers, imagines, the audience must infer from what the actor is doing with body and face and voice. But prose fiction can move in and out of a character’s mind with invisible speed and grace. Take Joyce—it’s lunchtime; Leopold Bloom in Davy Byrne’s pub orders a gorgonzola sandwich and a glass of burgundy; he sips the wine and looks around at the things for sale behind the counter:

Mild fire of wine kindled his veins. I wanted that badly. Felt so off colour. His eyes unhungrily saw shelves of tins: sardines, gaudy lobsters’ claws. All the odd things people pick up for food. Out of shells, periwinkles with a pin, off trees, snails out of the ground the French eat, out of the sea with bait on a hook. Silly fish learn nothing in a thousand years.

*

Another Willy anecdote illustrates both his frequent deployment of stage metaphors and his healthy Nabokovian contempt for theory and criticism. A girl in that first-year fiction workshop asked him what other classes someone who wants to be a fiction writer should take. His answer: “Language classes, definitely. An acting class. Maybe history, science….I don’t know, whatever you’re interested in. It doesn’t really matter. As long as you don’t take literature classes. Literature professors are the only people around here who might actually harm you as a writer.”

This surprised us. Pressed to explain why: Literature professors, he said—theorists, critics—might harm you as a writer because they’ll try to twist your head around and encourage you to think about literature in exactly all the wrong ways to think about it if you want to actually write it, rather than write about it. A literary critic is like a theater critic who sits in the audience on the opening night of a play. He only sees it when it’s done. He only sees what he’s supposed to see. There were months of work done by many people that went into this thing—the producer had to raise the money to back the production and hire a director, and the director had to hire the set designer and the costume designer and workers to make all these things, lighting techs and stagehands, had to hold auditions and cast the play, had to decide who should play which part, had to finesse all the interpersonal problems that inevitably come up, and all the actors had to study their parts, learn their lines, find their characters. Now it’s opening night. You, the director, are backstage. You see all the things that make it all work that the audience isn’t supposed to see—all the ropes and pulleys and trapdoors, machines that sometimes break and need to be fixed, that jug of water on the table and the stack of plastic cups. And all of this stuff—all the nuts-and-bolts work that goes into simply maintaining the illusion of narrative onstage after the proscenium lifts—has to be absolutely perfect before that theater critic sitting out there in the audience can even begin to start thinking about the stuff he wants to write about. Thinking about literature the literary critic’s way is getting ahead of yourself. You need to start months before his moment, back when the carpenters are nailing the sets together and the actors are standing around in jeans and T-shirts with their scripts in their hands, still struggling to memorize their lines.

Picasso memorably said more or less the same thing. Someone asked him about the differences in the ways art critics and artists approach art. “When art critics get together,” he said, “they talk about abstract matters—form and structure and meaning. When artists get together, they talk about where you can buy cheap turpentine.”

I did not follow Willy’s advice exactly—I took plenty of literature courses in college (and Willy, as my adviser, signed off on them). But as I did I never forgot his metaphor of the critic sitting in the audience. I was happy to discover works of literature I probably wouldn’t have found on my own, and I listened to what the literature professors had to say about them but kept them at an arm’s length, never drank the potion that turns people who might have been artists into academics.

Willy felt about literature the way Nabokov felt. That is, the right way. Please keep the “academic nonentities” with their collections of symbols and Greek myths away from it. Look at the man in the brown mackintosh standing at Paddy Dignam’s grave in Glasnevin Cemetery. Let art be irrational, mystical, raw. Let pleasure rule.

*

Several forces contributed to the decline of Willy’s career. One story is about the publishing industry’s loss of interest in Black authors that began sometime in the seventies, when the revolution began to feel over—at least for people in the publishing industry. The story Willy himself told was about his loss of interest in his career when weighed against the responsibilities of fatherhood. Another story that his students would tell each other involves the prodigious amount of weed he started smoking when he lived in Jamaica, a habit he continued to indulge unabated until his death (he was infamous among the buildings and grounds workers at Sarah Lawrence for the smell of pot smoke that emanated from his office when he was on campus); this might have been a factor in his fairly low output. There’s more stupid romance around harder substances but few chemicals are more hazardous to ambition than THC. But I’ve come to disbelieve this, considering the two novels he wrote after 1970 that never got published. The story I’m now inclined to believe is that the kind of literature Willy most loved and loved to create fell hard out of fashion in the past fifty years.

When I read Willy’s last novel, I feel like a child playing with my friend, and language is a vast and colorful ball pit that we are both gleefully splashing around in together.

Martin Amis wrote an essay in The New York Times appraising Anthony Burgess’s A Clockwork Orange on the novel’s fiftieth birthday. Burgess was a fellow worshipper of Joyce (Andres Restrepo told me that a friend of Burgess’s had once remarked that “he couldn’t pay a parking ticket without mentioning James fucking Joyce.”). I never had a conversation with Willy about Anthony Burgess but I wouldn’t be surprised if he was a fan—Burgess was also a musician, and a musician on the page. Amis concludes his essay with this:

In his 1973 book on Joyce, Joysprick, Burgess made a provocative distinction between what he calls the “A” novelist and the “B” novelist: the A novelist is interested in plot, character, and psychological insight, whereas the B novelist is interested, above all, in the play of words. The most famous B novel is Finnegans Wake…The B novel, as a genre, is now utterly defunct, and A Clockwork Orange may be its only long-term survivor.

Utterly defunct? Prose fiction that delights primarily in wordplay? There were others in Joyce’s generation, like Gertrude Stein. Later, Joyce acolytes—Flann O’Brien, Anthony Burgess, Gilbert Sorrentino, William Melvin Kelley. Nabokov, Thomas Pynchon, John Barth. One of my favorite novels of all time, Russell Hoban’s Riddley Walker. Irvine Welsh. Except for Irvine Welsh, all the “B” writers I can think of are either dead or very old.

*

As I’ve been writing about Willy, I have been rereading his books, including his last and weirdest novel, Dunfords Travels Everywheres. The first seven chapters are content-weird (Chig Dunford is living in an unnamed fictional European country with some extremely strange customs during a time of political unrest, hanging out with other expat hipsters probably modeled on people he knew in Paris in the late sixties) but not form-weird: in the beginning, the writing by and large is transparent, playing it straight. And then, eight chapters in, on page 64, this happens:

Witches oneway tspike Mr. Chiglye’s Languish, n curryng him back tRealty, recoremince wi hUnmisereaducation. Maya we now go on wi yReconstruction, Mr. Chuggle? Awick now? Goodd, a’god Moanng agen everybubbahs n babys among you, d’yonLadys in front who always come vear too, days ago, dhisMorning we wddeal, in dhis Sagmint of Lecturian Angleash 161, w’all the daisiastrous effects, the foxnoxious bland of stimili, the infortunelessnesses of circusdances which weak to worsen the phistorystematical intrafricanical firmly structure of out distinct coresins: The Blafringro-Arumericans.

This is Willy doing for Black America what Joyce did for Ireland with Finnegans Wake. And as with Finnegans Wake, the best way to read it is aloud (also the best way to understand it). A slumgullion of puns and references: the Black Panthers and the Nation of Islam are jumping around in this nutty bouncy-castle, and many other things that people were thinking about in 1970. Bizarre, hilarious phrases and sentences poke their heads above the water now and then: “give a gillion of that, and one only little shiny, Brightdear—and don’t have to worry about just any cadillacquered pushpoy”; “Oh son unsown why haven you foresuckered them?” This is without a doubt what Burgess called “B” writing, which is “interested, above all, in the play of words.” “Play” is the key word. I once heard an interview with Pharoah Sanders in which the interviewer asked a serious-sounding question about his “work,” which he answered, “I don’t work. I play.” The double meaning of that verb—what children do, what musicians do—what an artist should do. Play. If you write for pleasure, then someone might want to read it for pleasure. Not everyone, of course—but you’re not writing for everyone. (Anthony Burgess, in a Paris Review interview, asked if he imagined an ideal reader for his books, said, “The ideal reader of my novels is a lapsed Catholic and failed musician, short-sighted, color-blind, auditorily biased, who has read the books that I have read. He should also be about my age.”)

In Dunfords Travels Everywheres, after his jarring entrance, Black Finnegan’s voice continues for two chapters. I would guess that the moment when most readers who do not finish this book quit reading it is on page 73, when they wearily turn the last page of Chapter 8 praying for an end to this, and Chapter 9 begins in the exact same voice. Which is a shame, because if they continue to Chapter 10, they will get to experience this absolutely magical moment (Black Finnegan has been speaking for nearly twenty pages now):

Now will ox you, Mr. Chirlyle? Be your satisfreed from the dimage of the Muffitoy? Heave you learned your caughtomkidsm? Can we send you out on your hownor? Passable. But provably not yetso tokentinue the cansolidation of the initiatory nature of your helotionary sexperience, let we smiuve for illustration of chiltural rackage on the cause of a Hardlim denteeth who had stopped loving his wife. Before he stopped loving her, he had given her a wonderful wardrobe, a brownstone on the Hill, and a cottage on Long Island. Unfortunately, her appetite remained unappeased. She wanted one more thing—a cruise around the world. And so he asked her for a divorce.

She refused to give it to him.

The acid trip wears off mid-sentence, and we come back to “reality.” Black Finnegan has drugged us and flown us from Ruritania over the threshold of the unreal across the Atlantic and woken us up in New York, New York, USA, Reality. What follows is a story about a self-satisfied dentist trying to divorce his wife, who hires Carlyle Bedlow—the Dolokhov Willy always called up for a dirty job—to seduce her and somehow photograph her in the act, in order to produce airtight grounds for divorce. Willy the “A” storyteller returns, and—like an abstract painter who quits spraying paint from a squirt gun and picks up a palette and brushes to demonstrate he can also paint a representational scene with masterful but unadventurous technique—makes a story happen that rivets the reader’s attention and holds until it bleeds directly into another one, and Black Finnegan returns. His voice fades in and out of the novel several times like a lens filter that turns everything crazy for a stretch of pages and then disappears again. At first the reader is happy to hear from him, and by the end of these stretches feels relieved when he goes away.

*

I enjoy telling the anecdote of Willy warning us that the only people on campus who might harm our craft are the literature professors, and I enjoy telling it precisely because it shocks and discomforts people who humbly revere literature, those who enter a supposedly great book like a penitent crawls on his knees into a cathedral. Willy didn’t worship literature—he simply loved it. And the way he thought about writing fiction was startlingly concrete. When talking about a story I was working on, he tended to focus on basic nuts-and-bolts things like, say, whether or not the plot made any sense—i.e., the subjects that people with PhDs in literature don’t ever discuss (are in fact strictly warned away from discussing), but are essential to the craft. He really hated the idea of reading literature “through the lens of” Marx or Derrida or whatever. He had a healthy contempt of sophistry.

Willy knew how to read Joyce: Don’t read it because it’s difficult—i.e., in order to improve yourself, to make yourself smarter, or to make other people think you’re smart (and big philosophical ditto that for any extrinsic teleological reason for reading, including moral self-improvement)—read it for pleasure. It was written for pleasure. Reading it the right way, Willy taught me, is to partake in Joyce’s pleasure, to share it. Because once you stop reading it for a reason and start reading it for pleasure, the difficulty vanishes like snow in the sun. So does all poseury, pretension, sophistry, bullshit. Don’t work—play.

Art is supposed to be fun. When I read Joyce, and when I read Willy’s last novel, I feel like a child playing with my friend, and language is a vast and colorful ball pit that we are both gleefully splashing around in together: that is to say, my favorite kind of experience I can have with a work of literature. Bababadalgharaghtakamminarronnkonnbronntonnerronntuoonnthunntrovarrhounawnskawntoohoohoordenenthurnuk!

__________________________________

“My Soul Frets in the Shadow of His Language” by Benjamin Hale appears in the latest issue of Conjunctions.

Benjamin Hale

Benjamin Hale is the author of the novel The Evolution of Bruno Littlemore (Twelve, 2011), the collection The Fat Artist and Other Stories (Simon & Schuster, 2016), and the nonfiction book Cave Mountain: A Disappearance and a Reckoning in the Ozarks (forthcoming from HarperCollins, 2025). He has received the Bard Fiction Prize, a Michener-Copernicus Award, and nominations for the Dylan Thomas Prize and the New York Public Library's Young Lions Fiction Award. His writing has appeared, among other places, in Conjunctions, Harper's Magazine, the Paris Review, the New York Times, the Washington Post, Dissent and the LA Review of Books Quarterly, and has been anthologized in Best American Science and Nature Writing. He is a senior editor at Conjunctions, teaches at Bard College and Columbia University, and lives in a small town in New York's Hudson Valley.