Bill Hayes Writing About a Completely Normal Evening in New York

Or, A Scene From the Before Times

It is a spring evening in the Village about four years ago:

I stop by the smoke shop down the block. It’s six o’clock. Ali has arrived for work just as Bobby is finishing his shift. I’ve hardly ever seen them here together; it’s either one or the other behind the counter. They are talking about something with great vigor and animation—at least, that’s how it appears to me. I can’t understand a word they’re saying.

“Gentlemen. Gentlemen?” I can hardly get their attention, they’re so enthralled. Finally, I have to interrupt: “Hey, what are you two arguing about? And, which language are you speaking?”

“Panjabi,” says Ali, ignoring my first question. Bobby has walked away, into the back somewhere. Ali calls after him, as if getting in a final jab. He can’t disguise his delight. He is a cat waiting for the mouse to return to play.

Moments pass. Bobby is back at the counter, as if nothing had happened between them, and I have to smile: Here they are, side by side, these two from whom I’ve been buying Sunday papers and rolling papers, bottles of water and Kit Kat bars and poppers for the past seven years: one Muslim man, one Hindu, matching mischievous grins on their light-brown faces.

“Yes?” says Ali.

“Mr. Billy, what can we do for you?” says Bobby, feigning seriousness.

Now I can’t even remember what I came in here for, so I change course.

“Teach me a word in Panjabi,” I say. “Just one word.” “Okay,” says Ali.

“All right,” says Bobby.

They stare back at me, waiting for a prompt.

“Hold on, let me think. What is—um, what is the Panjabi word for beauty?”

They look at one another. “Sohni,” says Bobby.

Ali nods, “Yes, sohni,” then adds, “but it’s sohna if you’re talking about a man—sohna, not sohni.”

Ali: he knows me all too well.

“That is very helpful—thank you, Ali,” I say. “You’re welcome, my friend.”

On the day Oliver died, Ali was the first person to whom I told the news. He had gotten to know “The Doctor” well over the years, and they shared a mutual affection and respect. I remember how Ali came out from behind the counter to comfort me: “I will pray for the Doctor,” he said tenderly, “and for you.”

He’s been a constant in my life since, almost like a family member, despite the obvious differences between us, as he is a devout Muslim, Pakistani American, not to mention a husband, a father, and a vegetarian teetotaler—and I am, well, I am none of those things. I can’t walk past the smoke shop without at least waving or saying hello to Ali, if not stopping in to chat. And if I don’t, Ali spots me on his sidewalk surveillance cameras—and gives me shit about it the next time I come in.

Now, though, I haven’t seen Ali at the shop in about three weeks, and I’m beginning to seriously worry. The only times I’ve known him to be away for so long (besides his one day off a week) were when he’d gone back to Pakistan to see family—visits he made once every couple of years.

I’ve popped my head into the shop several times and asked whomever was behind the counter—men I did not recognize—about Ali: “Is he okay?”

Yes, they always said, he’s okay, but nothing more. Maybe they didn’t know? Maybe they didn’t want to say?

The other night, I saw the owner of the smoke shop standing out front, wearing an N95 mask. We’d met a few times before. I approached and said hello, while keeping a proper distance.

“How’s Ali? I haven’t seen him in so long. He’s not sick, is he?” “Yes, Ali’s sick, unfortunately,” the owner said.

No. Fuck.

I called Ali’s number the minute I got home but it went to voicemail. My heart sank. But he called me back a short time later. I was relieved and happy to hear his voice and told him that. “I hear you’ve been sick. Tell me—where are you, how are you doing?”

“I’m home. Yes, ill,” he said, “very, very bad.” It had started two weeks ago—high fever, coughing, weak, impossible to eat. “I felt like I’m done,” Ali said. “Done.”

Beyond the words he spoke, I could hear the fear in his voice. Without having to ask, I knew that his fear was more for his wife and two children—both now college students—than for himself.

“The fever would not go away,” he continued, “it was not easy, not easy, very painful, but then, the doctor gave me some pills— antibiotics.” He said he’d been able to talk to the doctor via “telemedicine,” a term that, at an earlier time, I would never have expected to hear from Ali. Or from me, for that matter.

“And the pills worked?”

At this, Ali sounded happy for the first time. “Oh yes, the fever went away. The cough, too. Thank God. Everything’s good now, thank God—”

“Yes, thank God, and your family—your wife, your kids?” “Everyone’s okay, everyone’s safe, healthy. Thank God, thank

God.” He sounded tired. Very tired.

I told him I’d keep him in my thoughts and check back in. We wished each other a good night.

__________________________________

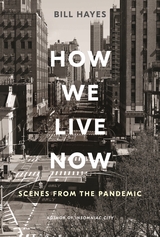

From How We Live Now by Bill Hayes. Used with the permission of Bloomsbury. Copyright © 2020 by Bill Hayes.

Previous Article

The Twilight of Democracy and the Rise of AuthoritarianismNext Article

Terrance Hayes ConsidersTrump vs. Poetry