Big in the Philippines: Why I Was Named After Karen Carpenter

On the Odd Affecting Power of The Carpenters

On February 4th, 1983, Karen Carpenter died of complications from anorexia nervosa while she was reaching for a fuzzy bathrobe in the bedroom closet at her parents’ midcentury suburban home in Downey, California. By all accounts—Ray Coleman’s 1994 biography chief among them—Karen spent the day before she died cruising between suburban chain stores, looking for sturdy household items like a washer-dryer at the Downey Gemco, a big-box store absorbed by Target in the mid-1980s that she affectionately referred to as “the Gucci of Downey.” She ate a shrimp salad for dinner with her parents at Bob’s Big Boy and picked up a couple of tacos to go from a local joint next door so she could snack on them while indulging in the made-for-TV spectacle of a manscaped, micro-kimono-clad Richard Chamberlain in Shogun. Everyone thought she was on the mend, the very picture of SoCal suburbanity in repose, eating tacos and watching the tube all night, before what was supposed to be another sunshiny day in an endless season—nay, a lifetime—of sunniness.

On the other side of the Pacific, a mere stone’s throw from the land of Shogun and newfangled devices like singalong karaoke machines, I learned about Karen Carpenter’s death in the waiting room of a dubious travel agency in Little Ongpin, Manila’s old Chinatown district. I was nine years old, stuck there with my musician parents. They were making arrangements for our departure from the Philippines, where I was born, to the dry heat of Southern California, where my white stepfather grew up just 50 miles east of Downey in a region called the Inland Empire: a place with its own aerospace and defense plants nestled between the citrus groves and the stucco.

Karen Carpenter Dies at 32 screamed the newsprint just above the fold of a Filipino newspaper discarded on the cracked, moist Naugahyde bench next to me. Even though my body had slackened while I was sweating it out in the tropical density of that miserable waiting room, cooled only intermittently by a half-cocked electric fan, my spine went stiff as soon as my eyes grazed that headline. ‘Sus Maryosep! I cursed in my head. My namesake is dead. And she died young—at 32, a year younger than Jesus himself.

At nine going on ten, I was just growing into my fear of mortality, which was aggravated by the fact that we were about to take another epic, transpacific journey on a jet packed with people chain-smoking duty-free Dunhills. At least this was how I remembered my first flight to the States when I was five. I also recalled the oxygen masks dropping somewhere past Guam, and my mother setting her half-drawn cigarette in the tiny armrest ashtray before strapping a mask over my face.

My family, comprising mostly professional musicians, made a lot out of the fact that I was named after Karen Carpenter instead of a relative, saint, or some other Catholic luminary. My grandfather and his brothers—Romy Katindig and the Hi-Chords—were credited with innovating Latin jazz in the Philippines in the 1950s and 60s. My mom, whose stage name is Maria, carried on the family business, briefly singing in OPM (original Pilipino music) acts in the 1970s with supergroups like Counterpoint and the Circus Band, before falling in love and forming a touring jazz combo with my stepfather: a California-born, Hawaii-based musician named Jimmie Dykes. His Pacific Rim roots landed him gigs with some of the top Filipino performers of the 1970s, including one of my mom’s godfathers, crooner Roberto “Bert” Nievera from the Society of Seven.

My mother’s voice was often compared to Karen Carpenter’s when both of them were in their prime, so Karen was like family—but more of a distant relative whose resemblance felt significant even if it was only circumstantial, and whose global accomplishments were touted as aspirational for my musical clan: Karen Carpenter, superstar.

Even before she died in 1983, Karen fulfilled something of a spiritual role in our home in Manila, like the friendly ghosts our neighborhood curandera claimed to have found living in our duhat tree, and with whom my grandmother Linda Katindig tried to negotiate one evening after several hours of mahjong and too many bottles of San Miguel beer. She asked the mother-daughter spirits not to manifest in front of us lest they actually scare us to death, even as she acknowledged and respected their own claims to residency and tacitly accepted their ubiquity. Karen, too, was everywhere: in the late-night sing-alongs around the water-damaged upright piano on the veranda, in the cook’s whistled refrains of “Top of the World,” and in my name. But most of the time, as the song goes, it was just the radio.

I challenge anyone visiting the Philippines, now or then, to try to last a day—nay, several hours—without hearing a Carpenters song on the radio, or in a karaoke establishment, or performed by a cover band. Though there aren’t any charts to prove definitively that the Carpenters were more popular in the Philippines than in any other nation in the world, their enduring presence on Filipino radio, and in Filipino American karaoke repertoires, attests to my people’s profound affinity with this most wholesome of American duos.

After all, the Carpenters famously crooned at Nixon’s White House during West German Chancellor Willy Brandt’s state visit, while our neighbors in Southeast Asia were ablaze in napalm and our own would-be dictator, Ferdinand Marcos, was declaring martial law. Their Now and Then album from 1973, the same year my teen parents (who met performing in a Manila concert production of Jesus Christ Superstar) christened me Karen, has been clocked by Tom Smucker as “one of the greatest pop music explorations of whiteness in the last half century.”

I challenge anyone visiting the Philippines, now or then, to try to last a day—nay, several hours—without hearing a Carpenters song on the radio, or in a karaoke establishment, or performed by a cover band.

The Carpenters’ westward migration from New Haven, Connecticut, to Downey, California, a white, working-class suburb conveniently situated between Orange County and Los Angeles, would seem to affirm this narrow trajectory toward “whiteness and promises,” to invoke a Filipino karaoke machine that misinterpreted the line about “white lace and promises” in “We’ve Only Just Begun.” Both the original lyric and the error are essentially referring to the same thing: an American suburban fantasy of the good life, with a good wife, “sharing horizons that are new to us,” but not foreign or strange in the grander scheme of things. Familiar. Comfortable. Just as things should be. Or at least as we always pretend we want them to be. As Smucker writes, “Control and precision—often assigned as white musical values—and elaborate pop production that implies a kind of mass affluence, locate the Carpenters’ soft rock in the suburban world abstracted on the Now & Then album cover.”

It’s easy enough now for scholars, historians, and music critics like Smucker to point out with 20/20 hindsight how harmless the Carpenters were, implying that Karen, Richard, and their team were blithely unselfconscious about the incompatibility of their “goody-fourshoes” image with the zenith of late-1960s counterculture. The Carpenters came to prominence during a particularly tumultuous era in the United States, both musically and politically. In the wake of the summer of love, Woodstock, and the escalation of the war in Vietnam, Karen’s voice—described by detractors as “saccharine” and championed by others as distinctly “smooth” or “velvety”—began to dominate the airwaves with both nostalgic reflections and optimistic projections about better times crafted from “only yesterdays.” Mired in the Watergate scandal and with his days in office numbered, Richard Nixon took the opportunity to take a break from his legal and political woes to describe the duo as “young America at its best.”

Richard Carpenter chafed at the creepy wholesomeness of their image, and in particular at how A&M records marketed the duo in soft-focus, vaguely romantic poses among jutting rocks on picturesque seashores. “[The Close to You cover] looks like a Valentine’s card. We’re not sweethearts,” he complained in a 2002 BBC documentary, Close to You: The Story of the Carpenters. Sure, the music itself is mostly romantic, from the first blush of affection’s wanton anthropomorphism in “(They Long to Be) Close to You,” to enduring love’s auspicious commencement in “We’ve Only Just Begun.” But the messengers, Richard insisted—felt he had to insist—were not.

In the same BBC documentary, John Bettis, Richard’s lyricist and songwriting partner, unabashedly declared that in 1970, the year the Carpenters first topped the charts, “Everybody was dying to be something they weren’t. Everybody was dying to be from the ghetto. Everybodywas dying to not be from the suburbs. The fact of the matter was that we were who we were, and we were white, middle-class American kids. And we wrote like that, sang like that; we dressed like that; we lived like that.”

*

Needless to say, my musical family was not—is not—like that, despite the belated addition of my Southern Californian stepfather to the mix. By the time I was born, in 1973, the Katindigs were genteel, post-provincial, post–World War II Manileños, or Manila-dwelling prototypes for what we now call the bourgeois-bohème: hedonistic artists with some capitalist success and an aspirational, rather spendy sensibility. Unlike the middle-class American white kids, who Bettis speculates are drawn to the authenticating grit of a “ghetto” past, the Katindigs made every effort to transpose their war-torn, provincial Pampangan origins, and their scrappy upbringing in the working-class Manila neighborhood of Obrero, Tondo, into a hip, internationalist Latin-jazz sound for the finest lounges and cocktail bars of southeast Asia and even the United States.

In 1970, the year the Carpenters released their first number-one single, “(They Long to Be) Close to You,” my grandfather Romy Katindig and his brothers, the Hi-Chords, were performing regularly in Las Vegas. As his younger brother, Eddie, the vibraphone and sax player who eventually came to be known as “the Kenny G of the Philippines,” noted in an interview for a book called Pinoy Jazz Traditions: “This was about 1969, and we were playing all over America for four years. We would do a lot of shows. We fronted for Count Basie’s Big Band and also for Peter Nero. The Tropicana Hotel in Las Vegas was one of our puestos [regular venues].”

The Carpenters played the nearby Sands and Riviera, and part of me wonders if either family ensemble ever noticed the other gigging on the strip, even unconsciously, in passing. At the very least, I fantasize that my grandfather knew and cared about who the Carpenters were and would keep an eye out because his teenage daughter was such a huge fan. But as with most things having to do with this charming man, his attentiveness to his daughter’s interests, especially from half a world away, is likelier to have flourished in fantasy than in reality.

My grandmother, who remained in the Philippines with my mom and my uncle during Romy’s years on the road, was a highly educated mestiza from Iloilo in the Visayas. Linda Oñas was born to Juan Oñas, a US naval officer of Spanish-Filipino descent, and his devoutly Catholic wife, Salud. My great-grandfather Juan died of tuberculosis before World War II, leaving Salud to raise their two daughters, Linda and Mellie, on her own. Together these three fled through Visayan rice fields, ducking Japanese bullets, while concealing the ceremonial American flag bequeathed to Salud by the US Navy after Juan’s death. She eventually dismantled the stars and stripes, both burdensome and dangerous in her possession, and repurposed the fabric as school dresses for my grandmother and greataunt during the colonial occupation.

After the war, the Oñas women moved to Manila, where my grandmother, Linda, met Romy Katindig in the early 1950s. She fancied herself a gal about town because she held an urbane secretarial job—think Peggy Olson in Mad Men—of which she was particularly proud. Romy, whose given name, Romeo, is entirely too apt, was the pianist and arranger for a radio show that recorded live in the big city park, Luneta, now Rizal, Park—near my grandmother’s corporate office. They met during one of her lunch breaks, and though she was suspicious of his caddish charms, they eventually ended up marrying in a proper Catholic wedding at Salud’s insistence after my mother had already been conceived.

My mom—christened Elizabeth before she adopted her stage name, Maria, for the business called “show”—inherited my grandmother’s poised mestiza femininity and my grandfather’s drive for musical adventure and stardom. When we first visited the Southern California suburbs in 1978, about five years before we would eventually settle there, I could tell she was disoriented by not moving easily through this new environment with an air of specialness and privilege. She possessed, if not exactly whiteness, a light-skinned middle-classness that she and my grandmother wielded so well in Manila, only to be confronted in Riverside, California, with a working-class American suburban whiteness neither of us quite understood, let alone knew how to navigate.

My mother was stunned when the neighborhood kids encircled me on her soon-to-be mother-in-law’s neatly clipped lawn to ask what I was, where I came from, and whether or not I was Christian. When I responded that I was Filipino and Catholic, these nasty little inquisitors asked if I “ate people” and knew how to use a toilet. They also told me, “Catholics aren’t Christians.” Evangelical Christianity at its densest.

Richard Carpenter chafed at the creepy wholesomeness of their image, and in particular at how A&M records marketed the duo in soft-focus, vaguely romantic poses . . .

My white soon-to-be-grandmother, Marion Dykes, shooed them away with a sternness and gravitas I came to understand later as a holdover from her deeply ingrained midcentury decency. I appreciated her sense of decorum in those kinds of situations though I never could keep my elbows properly off the table during dinners at her home, which usually involved stewed tomatoes and other items peculiar to my young Filipino palate, with my preference for the charred, fatty parts of grilled meats.

My mother was only 15 in 1970 when the Carpenters’ album Close to You went platinum in the United States and across the globe. She began to sing their repertoire in her earliest coed vocal groups around the same time. These groups were inspired stylistically by the Carpenters’ cultivation of a pop choral sound, which could be described as next-level Fifth Dimension: more complex key changes, and more intricate jazz harmonies, which matched well with my mother’s own musical heritage. By the time I was born, several years later, my namesake, Karen, and the Carpenters were ensconced firmly at the top of the charts, and my mother too hit her stride in her career.

From 1970 to 1973, the Carpenters had notched hit album after hit album, from their eponymous 1971 follow-up to Close to You to my soundtrack in utero, the 1972 masterpiece A Song for You, which boasted some of their most enduring original hits, including “Top of the World,” “Hurting Each Other,” “Goodbye to Love,” and “I Won’t Last a Day without You.” Mom’s singing career was derailed ever so slightly by my impending birth and a brief, tumultuous marriage to my biological father, a tenor named Henry Tongson, who also adored Karen Carpenter’s voice. It was inevitable I’d be baptized as Karen by these 18-year-old parents and superfans who met singing in the Circus Band, one of Manila’s hottest acts, known for performing more than the occasional Carpenters cover.

Once this Karen made her way into the world, into a Manila newly under the thumb of Ferdinand Marcos’s martial law, the Oñas matriarchy, which was reconstituted in the late 1960s after Romy Katindig absconded with one of his overseas lovers, circled the wagons. My grandmother, my great-grandmother, and my great-aunt helped raise me (as they had raised my mom), while Maria took a choice gig performing nightly at a tony supper club called the Top of the Hilton with the Carding Cruz band. It was several years into her residency at “the Top” that she met Jimmie Dykes, the musical director for Bert Nievera’s touringshow, who shared the bill with her act for the better part of a year.

Like my mother’s father, her younger brother, and the self-described “Piano Picker,” Richard Carpenter, Jimmie was a pianist and arranger. By 1977, just as the Carpenters seemed to be losing their platinum magic with experimental forays into proggy futurism, like “Calling Occupants of Interplanetary Craft (The Recognized Anthem of World Contact Day),” my mom and soon-to-be-stepdad were taking copious couple photos around Manila’s landmarks in matching astrology tees and denim bell bottoms—he’s a Leo, she’s an Aries. Unbeknownst to me—I was barely past toddlerdom at the time—our own westward trajectory to the Southern California suburbs was being set into motion, and they wanted to remember Manila when they left.

_____________________________________

Excerpted from Why Karen Carpenter Matters by Karen Tongson, © 2019, published with permission from the University of Texas Press

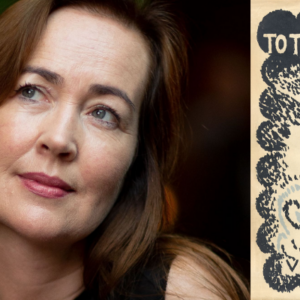

Karen Tongson

Karen Tongson is Professor of Gender & Sexuality Studies, English, and American Studies & Ethnicity at the University of Southern California. She is the author of Why Karen Carpenter Matters and Relocations: Queer Suburban Imaginaries. She also co-hosts the podcasts Waiting to X-Hale and The Gaymazing Race.