Big Business, Small Town Ideals: On Midwestern College Football

Ben Mathis-Lilley on the University of Michigan and the Allure of Winning

College football is in some sense Thomas Jefferson’s fault. Higher education in what would become the United States initially revolved around schools like Harvard and Princeton, which at the time provided religious and “classical” (Latin, Greek, etc.) educations to future members of the clergy and others in the social upper class. Jefferson had a lot of thoughts about this, as he did about every other subject, and he believed that such a limited scope of education was inadequate to the kind of country he wanted the United States to become, in which every citizen (if they were a white man) would be equipped by institutions of learning, equal in stature to those in Europe, to handle their own farm or business and to participate in the public discourse of democracy.

With this end goal in mind, his vision for American education was one in which everyone “from the highest to the poorest” would receive public schooling to some degree, with the most promising (among white men) passed on to higher levels regardless of their original social status. Even at the most advanced levels, Jefferson wanted curricula to cover subjects of practical use like chemistry, agriculture, and the practices that would soon thereafter be referred to as engineering.

He agitated constantly to create a federal flagship university and associated schooling system; he didn’t succeed in this even as president, but he did found the University of Virginia, which became a model for the many (relatively) egalitarian state universities across the country that aspired to create graduates who were both economically productive and well-read. He was also one of the main influences on the Land Ordinance of 1785 and the Northwest Territorial Ordinance of 1787, which allotted land that potential new states were required to sell or lease in order to fund public education.

Sixty years later, the Morrill Land-Grant College Act of 1862 would give away more land (which, to be clear, was in federal possession only because it’d been taken from the Indigenous people who’d been living on it for thousands of years) for the purpose of starting even more colleges. That bill’s sponsor, Vermont Representative Justin Smith Morrill, echoed Jefferson in saying that he hoped the institutions to be launched would be “accessible to all, but especially to the sons of toil.”

The connection between college and football now strikes many people as arbitrary, but when viewed historically, it may have been inevitable.

The University of Michigan, in fact, was cofounded by a man named Augustus Woodward, who had been appointed by Jefferson in 1805 to be the Michigan Territory’s chief justice. With the self-confidence typical of guys and dudes of that era, Woodward decided that the university should be organized around thirteen categories of knowledge that he had defined and named himself.

Michigan never used Woodward’s system, however, because while it was technically founded in 1817 as a Detroit institution, it didn’t have the resources to actually teach any students until 1841, at which point it was located in Ann Arbor because that was where some local white landowners had some land. (The United States bought the southwest corner of the state from several Native American tribes in 1807 for $10,000 and an agreement to make $2,400 in annual payments going forward.)

According to Howard Peckham’s 1967 book The Making of the University of Michigan, President James Monroe later decided not to reappoint Woodward to the judgeship after the members of the Detroit bar complained in writing about “his entire want of practical knowledge.” Monroe gave Woodward a job in Florida instead, in an early foreshadowing of the type of guys who would end up populating Florida.

The University of Michigan’s story from there is one of essentially continuous expansion along the lines for which Jefferson would have advocated. In 1855, U of M added a science curriculum; in 1865, it surpassed Harvard to briefly become the largest university in the country by enrollment. It was led by a series of presidents who enacted what were, for their time, progressive policies such as making chapel services optional and letting students select specific classes and areas of study. (Most notable among these presidents was James Angell, who negotiated the installation in his official residence of Ann Arbor’s first indoor toilet as a condition of taking the job.) In the early twentieth century, the university became a destination for Jewish students on the East Coast who had been excluded from Ivy League schools by anti-Semitic quotas.

Michigan was concurrently prospering as a state. It was initially covered in white pine trees, which were in demand for construction in part because they were very tall and had few branches below the canopy level, which made for a desirable ratio of smooth to knotted wood. Per the Bureau of Labor Statistics, Michigan was the top lumber producer in the country during each of the first three censuses taken after the Civil War.

As that industry declined because there were no more white pines to harvest, some of the fortunes it had created were invested in the burgeoning automotive sector, which subsequently did pretty well as far as making a vast amount of money and completely changing the nature of day-today existence. Detroit’s population grew from roughly 285,000 in 1900 to 1.8 million by 1950, and Michigan’s per capita income in 1955 was 16 percent higher than the US average.

U of M accrued a truly impressive account of relevance, most of it good. It opened the first university-owned hospital; an early medical graduate, William James Mayo, went on to work with his brother in the practice that became the Mayo Clinic. Clarence Darrow attended the law school for a year before dropping out to finish his preparation for the bar privately.

Philosopher John Dewey was a professor in the 1880s; Robert Frost was a visiting teacher in the 1920s. Leo Burnett, the founder of modern advertising, overlapped on campus with Branch Rickey, who would go on to sign Jackie Robinson to the Dodgers; Arthur Miller overlapped with Gerald Ford. Mike Wallace, Gilda Radner, and Bob McGrath (from Sesame Street) were alums, while Iggy Pop (who in 1995, well after becoming a rock icon, manifested the well-rounded Michigan ideal by writing a short review of The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire for a classics journal) and Madonna dropped out.

The announcement that Jonas Salk’s polio vaccine was effective took place in Ann Arbor—Salk had previously worked at the school of public health—as did John F. Kennedy’s introduction of the Peace Corps and Lyndon Johnson’s introduction of the Great Society (i.e., Medicare and Medicaid). The Students for a Democratic Society’s Port Huron statement, the defining sixties declaration of leftist principles, was written while SDS leader Tom Hayden was a student (Port Huron is one hundred miles away).

The militant Weather Underground group and the weather app Weather Underground both have U of M roots, the latter as a nod to the former, which is actually kind of weird. Jack “Dr. Death” Kevorkian was a 1952 med-school graduate. And needless to say, we must not forget the Unabomber (MA ’64, PhD ’67).

The school’s place in the American imagination perhaps reached its apex in the 1983 movie The Big Chill, which was cowritten and directed by Lawrence Kasdan, an alum who had just come off writing Raiders of the Lost Ark and the original Star Wars sequels. The characters in The Big Chill are semi-disillusioned friends reuniting for a funeral fifteen years after graduating from college; in the film, their biographies and arcs are constructed so as to encompass the breadth of (white) baby boomer experience.

The school that these representatives of the zeitgeist attended together is Michigan. At one point, they watch a Michigan–Michigan State football game on TV and, in a true-to-life depiction, complain bitterly about the team. Jeff Goldblum’s character says they always “fold in the fourth quarter.”

Ah, yes—Michigan, like other state universities, also had football. (In real life, the program beat Michigan State in the game whose footage was used for the movie and went on to win the Rose Bowl that season. Suck on that, Jeff Goldblum!) The connection between college and football now strikes many people as arbitrary, but when viewed historically, it may have been inevitable.

The higher education system Jefferson helped create was a novel one by the standards of the rest of the world; rather than being controlled by a central government or church, each state’s system competed with every other’s for students and had to find its own funding. (The states and territories in which they were located were themselves competing for residents and investment money.) America’s ivory towers, whose occupants are often imagined to exist apart from the pressures and tawdry incentives of normal life, are actually engaged in constant competition for popularity, wealth, and prestige.

For this reason, Professor J. Douglas Toma explained in a 2003 book called Football U, colleges wanted members of the local population, even if they weren’t alumni, to feel like part of their community because it meant their children might end up as paying students and their representatives in state legislatures might be more generous with budget assistance. Local business owners and other civic leaders likewise benefited from universities that became regional and national beacons.

As Paul Putz, a Baylor University historian (and Nebraska native and University of Nebraska football fan), told me, “That sense of competition between states is also related to the autonomy and independence that states would claim for themselves in places like Virginia or Michigan.” He went on, “It’s not just symbolic, but it is very much about power and control of resources, tied in with the competition for new residents. So if you’re wanting to attract people to your state and then get them to move there, a university or a college could be important.”

The sport allowed colleges to attract attention while fulfilling a core social mission (preparing the most promising children from farm communities to manage smelting facilities and so forth).

At the time when many of the United States’ colleges were founded, domestic travel and relocation were time consuming and expensive, which meant both that state identity was more important vis-à-vis national identity than it is today and that being able to train professionals locally was a practical necessity. Said Putz,

If we think about region and place in the nineteenth-century world, there’s far more isolation than today. They’re constructing railroads, but the transcontinental railroad isn’t in place until after the Civil War. New technologies like the telegraph are emerging, but it still takes a long time to move from place to place. So there’s much more rootedness. Of course there is migration, but people are often moving from one isolated community to another. Distance matters. And so it becomes more important for states to have an institution of higher education where they can train their people. This is connected to the nation, this is connected to a sense of American identity, but it also is connected to a sense of place and purpose for a particular territory.

The game of American football—which evolved from rugby in the second half of the nineteenth century via rules adjustments made by, among others, Yale’s Walter Camp—fit into this array of circumstances perfectly. It appealed to college-aged men, it attracted local interest and built local pride, and it rewarded strength, strategic intellect, and organizational efficiency.

The game first caught on in the Ivy League; as Putz explained, this East Coast version of the game had pretensions to the aristocratic English ideal of amateurism, in which sports were kept separate from business so as not to corrupt the spirit of competition and self-betterment for its own sake. But as college football began attracting paying customers, educational leaders expressed alarm. How could they maintain an amateur ideal when business was clearly booming?

This concern—and, one might argue, the reality that its member schools already had more money and prestige than anyone else and did not need their sports teams to build more of it—would eventually lead the Ivy League schools to abandon big-time football in favor of a more modest approach. The Midwest’s spin on the idea, however, was that you could do big business and still have ideals—that it was actually good for ostensibly “amateur” scholars to play a violent game within a commercial milieu because it prepared them to dominate the rest of their lives in the same way.

The sport allowed colleges to attract attention while fulfilling a core social mission (preparing the most promising children from farm communities to manage smelting facilities and so forth) as well. Many of Michigan’s collections are digitized; when you search them for the word football, papers and photographs come up that were collected as students by enthusiasts of the sport who went to on to become distinguished alums in robust, manly Manifest Destiny fields like lumber, automobiles, and shipping.

The unofficial spokesman for the Midwestern football ideal was Amos Alonzo Stagg, who coached at the University of Chicago—at the time, a Big Ten powerhouse. Said Putz, “In 1931, Stagg is interviewed, and he’s asked about the excesses of sports. They ask him if this whole overemphasis on winning and the attention we give to college sports, isn’t this corrupting young people? Isn’t it ‘low and unworthy’? And he responds, ‘Low and unworthy! Low and unworthy, to want to win? Golly, man, isn’t that what life’s all about?’”

_________________________________

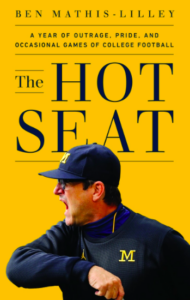

This article has been excerpted from The Hot Seat: A Year of Outrage, Pride, and Occasional Games of College Football by Ben Mathis-Lilley. Copyright © 2022. Available from PublicAffairs, an imprint of Perseus Books, LLC, a subsidiary of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

Ben Mathis-Lilley

Ben Mathis-Lilley is a senior writer for Slate.com, where he writes blog posts, columns, and feature stories about news, politics, and sports. He worked previously at New York magazine and, briefly but gloriously, as the editor of BuzzFeed’s sports section. He lives in New Jersey.