Homecoming: How To Be a Returnee in Lagos

Yemisi Adegoke on Returnee Privilege and the Africa You Don’t See on TV

I was one of three black girls in my sixth form politics class and I was the “loud one,” a label I’d been christened with since primary school. I was comfortable with the identity I’d been given and back then I didn’t think too much about the connotations of being a “loud black girl.” For me it was simple: I liked talking, I had opinions and I liked having them heard.

There was nothing more enjoyable to me than hijacking a boring lesson by turning it into a discussion about something, anything else. Intellectual back-and-forths, or as intellectual as you can be as a teenager, were fun for me. Not so much for my teachers, who made sure to note my propensity to talk and distract others in every class report.

Like most black teenagers born and raised in a country they’re repeatedly told isn’t really theirs, I was given several versions of the “thrice as good” lecture by my parents, who always let me know my sex and race were strikes against me. Still, I was young, naive and optimistic enough to keep talking anyway, and my politics class was no different.

My class was exactly how you’d expect a sixth form politics class in the early 2000s to be: full of idealistic, curious teenagers, trying to make sense of the ever-changing world around them. It was my favorite class because, naturally, there were plenty of opportunities to have conversations and argue ideology.

One day, we were discussing Africa, and one of the boys wondered why the continent was so poor. His tone was confident. He’d never set foot there, but he barely paused for breath as he reeled off his pick ‘n’ mix of the continent’s stereotypes: mud houses, starvation, disease, war. . . I remember instantly feeling jarred. It wasn’t just his smug confidence that irked me; it was the way he was talking about Africa.

As a Nigerian born and brought up in the UK, this type of negative stereotyping wasn’t exactly new to me. I wasn’t born when Live Aid aired but grew up in its very long shadow. For my generation, Africa was the opposite of cool. It was portrayed as a primitive, backward, war-torn monolith, where people spoke weird languages and had weirder names.

I’ve lost count of the number of times the African kids in my politics class would either band together to challenge what was being said, attempt to ignore or deflect it, and direct the heat onto something or someone else. But that day, as his stream of uninformed opinions continued uninterrupted, I could feel my temper rising. This was personal, and being the loud one, there was no way I could keep quiet. I looked over at the two other black girls in my class (who were also African), our eyes met in a sort of silent agreement and the three of us got “in formation,” taking down his points one by one.

Our teacher, who was a good-humored woman most of the time, let us argue for a little bit until we were pulled back into the lesson of the day. But the feeling that the “dark and hopeless continent” trope had reared its ugly head didn’t dissipate. I remember going home, still burning, as I relayed the whole exchange to my Mum.

In all honesty, the trope had never dipped its head to begin with. Centuries before Live Aid, the narrative of a primitive, war-torn, diseased and impoverished continent (or country as it’s usually referred to) prevailed. If the Western media was to be believed, nothing good had ever come out of Africa, apart from maybe the animals, and even those were only good within the safe confines of a safari park or as a trophy on a wall.

For my generation, Africa was the opposite of cool. It was portrayed as a primitive, backward, war-torn monolith, where people spoke weird languages and had weirder names.

The late Kenyan writer Binyavanga Wainaina challenged this myopic characterization in his 2005 satirical essay “How To Write About Africa” which touched on the many ways Western reporters and writers continuously get the continent wrong. He advised would-be authors to “treat Africa as if it were one country,” and not to “get bogged down with precise description. Africa is big: 54 countries, 900 million people who are too busy starving and dying and warring and emigrating to read your book.”

Little under a decade later, Amy Harth’s paper, “Representations of Africa in the Western Media: Reinforcing Myths and Stereotypes,” shows little has changed. Harth lists a series of myths and stereotypes that shape media coverage, including myths of lack of progress, lack of history, poverty, population, hopelessness and so on. Harth goes on to state that these myths and stereotypes are largely accepted because “when the media presents a story, it is not merely a story, but the story. The media’s role in representing Africa is definitive. It’s because of this role that they have the power to reinforce myths and stereotypes, which might otherwise be difficult to sustain. Their misrepresentation becomes the primary or only representation of the continent.”

That afternoon, in class, my teenage self had been confronted by these lazy tropes yet again, and again I wanted to challenge them. Since my words hadn’t worked, I thought that pictures might. My Dad was doing some work in Angola at the time and we had some brochures around the house showcasing beautiful homes and skylines in Luanda.

I spent all of that evening compiling a collection of these brochures, eagerly looking forward to the next day’s confrontation. I was determined to show my classmate the “positive side” of the continent; it wasn’t all sadness, wasn’t all disease, wasn’t all war. But in the end, he only shrugged as he looked through the brochures: it wasn’t that serious to him. But it had always been serious to me and it continued to be; whenever I heard negative reports about the continent, I’d try and counter it with stories about something positive.

By the time I finished my post-grad degree, eight years later, it looked like certain sectors in the Western world were beginning to look at Africa differently. Some African countries were experiencing strong economic growth, which led to a stream of stories highlighting the continent’s emerging middle class, the spread of the Internet, mobile phones and later, social media. People seemed excited, hopeful even. In 2000, The Economist ran a cover story proclaiming Africa as “the hopeless continent,” using every trope available. Eleven years later, the magazine changed its tune: “Since The Economist regrettably labeled Africa ‘the hopeless continent’ a decade ago, a profound change has taken hold.”

Now, the magazine declared, Africa was rising.

For Africans in the diaspora, like me, this shift in perception simply proved what we’d been saying all along; there’s a lot more to the continent than you think. The speedy adoption of social media “back home” helped push the “Africa rising” narrative even further. More people that looked like us, were sharing their own realities of the continent with the world, without having to go through the gatekeepers of the Western press or the gaze of eager voluntourists.

For me, this opened up a new dimension to my relationship with my country of origin. I’d been to Nigeria a handful of times, but it was always for some kind of family event. I had little to no concept of the country outside these heavily sheltered and short trips, but now, for the first time, through social media I was able to see what fun without the family looked like. And honestly, it looked amazing. Instagram Nigeria was the epitome of the “Africa they don’t show on TV”: beautiful beaches, beautiful people, beautiful smiles. Why wasn’t anyone showing this side of the country?

There was also an interesting trend: young people were choosing to leave the diaspora to move to Nigeria. For some, moving back to Nigeria had always been part of the plan, the diaspora was simply a place to get an education or some work experience, but Nigeria was home. But for others, like me, it wasn’t. We’d never lived in Nigeria before, but suddenly found ourselves diving headfirst into moving there.

I’d never considered it before until my Dad, who had moved there a few years earlier, suggested it after my first solo trip to Lagos. A friend and I had visited the city, and it was the first time I’d seen it on my own terms. It felt brand new, so exhilarating and so different from home. I couldn’t stop talking about it when I got back. But the idea of actually moving there seemed outlandish, at least at first. It wasn’t exactly practical: I didn’t know anyone in Lagos apart from my Dad and a handful of family members, I didn’t have a job, I didn’t know the system, I had no friends there. I’d essentially have to start from scratch.

Instagram Nigeria was the epitome of the “Africa they don’t show on TV”: beautiful beaches, beautiful people, beautiful smiles. Why wasn’t anyone showing this side of the country?

But the opportunity to do something different was so tempting. I was a journalist, trying to change the world through telling stories. The one-dimensional scope of reporting on Africa hadn’t changed enough for my taste and by going back I could contribute to the narrative shift: showing more of the good and not the bad, echoing Harth’s idea that “African news must also challenge the stereotypes and myths which cause current coverage to misrepresent Africa.”

According to my Dad, lots of young people in the diaspora were moving back and doing well for themselves, why couldn’t I? So I did. It was exhilarating, but at the same time extremely overwhelming. I quickly learned that being a Nigerian in Croydon, South London, is not the same as being a Nigerian from Croydon in Lagos, Nigeria.

It took me slightly longer to dig deep into my place in Nigeria’s social hierarchy. In the early days it felt so nice not to have to constantly navigate daily microaggressions that I didn’t think much about it. When I first arrived, a tight-knit community of “returnees”—one of many names given to people who relocate—helped me settle in. They showed me what Lagos life was like beyond Instagram.

They were people who had moved back from the US, from Canada and Europe, and of course their motivations varied. Some came back by choice, others by force, some had never lived in Nigeria before, others had left to get educated and had always planned to return. Some came back to explore the country, others to expand their horizons, but most came to tap into the vast opportunities we’d all been told about: economic, social, or simply being able to take advantage of the weaknesses of a corrupt system and thrive. There were also some returnees who wanted to “save” Nigeria. Armed with big ideas, naiveté, and boundless enthusiasm they moved back because they were compelled to change things, to make a difference.

I fell into this category and wanted to do my bit through my storytelling, but I soon learned Nigeria didn’t need positive stories, what it needed was balanced and nuanced ones. Storytelling that acknowledged the flaws, faults and challenges (ignoring them simply diminishes the majority for whom these things are a reality), but that also shows the hundreds of other things that make up the tapestry of the country. Just as the US and UK are not defined by just one thing, Nigeria, and other African countries shouldn’t be either, they should be afforded the same benefit as other countries and have their whole story told.

The naiveté and optimism of many returnees isn’t necessarily a bad thing. There’s no harm in trying to change any environment for the better but I’m worried about an uncomfortable dynamic emerging. Returnees are forming a sort of new elite. There is an important caveat here, not all returnees are created equal—there is of course the ruling class of Nigerian elite. The son of a billionaire businessman who went abroad to do a Masters, and a girl who grew up in a working-class home in South London, do not necessarily move back to the same version of Nigeria. The latter may not have the immediate connections, knowledge of the country or the capital to hit the ground running, but the two are bound by the perception that they’re at a level above almost everyone else. And this perception is problematic.

I quickly learned that being a Nigerian in Croydon, South London, is not the same as being a Nigerian from Croydon in Lagos, Nigeria.

It reminds me of the Biblical parable, “The Prodigal Son.” We, the returnees had gone abroad and “enjoyed” all the spoils of the diaspora. Meanwhile, our father, Nigeria, had been waiting patiently, full of hope for us to return home, and now we had. In those first few years, each time I met an older person (especially one affiliated with the establishment) and they found out I’d relocated, they reacted joyously. “It’s people like you we need in this country,” they’d say, even when they knew very little about me. Their joy had nothing to do with me, but more to do with what they thought I represented.

In the Biblical story, the father tells his servants to give his returning son his “best robe, a ring for his finger and sandals for his feet.” Then he instructs them to kill a calf and throw a feast. There aren’t robes and calves for us, but we are rewarded. Even for returnees who start from scratch, like I did, there’s scratch and there’s scratch.

Foreign accents alone make it easier for people like me to gain access, which is valuable currency in Nigeria. Irrespective of whether you’re actually qualified or not, it helps get a foot somewhere in a door that is otherwise firmly shut; if you happen to be qualified, a degree from a foreign institution, it means more respect, better jobs, better wages and a speedier climb up the ladder.

Returnees are positioned as the hope the country needs, free of the corruption that has infiltrated everyone else. Having experienced the world beyond Nigeria, it is understood that we know how things are supposed to be, and we can make them so. To make matters worse some returnees not only buy into this idea but actively strive to replicate and enforce the classist and oppressive structures that exist on the ground. Rather than push for change, as the returnee mantra goes, they are quite happy to be absorbed into the status quo and to ascend to the top of the food chain.

This is not to say there aren’t people who have moved back who are exceptionally qualified, with many things to offer, who have done and continue to do excellent things; there are many. It’s not to say either that there isn’t a role for returnees to play in the development and progress of Nigeria; there is. What that role is, I don’t quite know, but I do know Nigeria doesn’t need “returnee saviors.”

The idea reinforces the dangerous myths identified by Harth. One that immediately springs to mind is the myth of a lack of progress: the idea that Nigerians living in Nigeria have done nothing to try to improve the current state of affairs and they therefore need returnees to swoop in and save the day. This kind of erasure totally dismisses the ongoing work and efforts of people for whom moving to other countries is not an option. For them, Nigeria is the only reality that exists.

I remember a would-be returnee talking passionately about how much she wanted to kickstart a “real” feminist movement in Nigeria, because the country seemed to be making such little headway in the fight for women’s rights. While the latter part of that sentence is true, nothing she was suggesting was different from what hundreds of thousands of women in Nigeria had been diligently doing for decades. Why did she not want to join and support them? People who were already knowledgeable, familiar with the terrain and all the ins and outs of the country?

Rather than push for change, as the returnee mantra goes, they are quite happy to be absorbed into the status quo and to ascend to the top of the food chain.

This behavior carries echoes of the white savior “gap year” trope that we have criticized for years. Someone with little knowledge of a country decides they want to go there and start an initiative: perhaps it’s teaching young people how to read, or some kind of health drive or another noble cause. There’s nothing intrinsically wrong with this, but at times it comes with the assumption that “these kinds of things don’t exist, and only I can do them.”

In most cases this simply isn’t true. There are lots of people doing or trying to do these things, they have the experience, they have the knowledge, they may not be perfect but that’s where partnership and collaboration comes in, working with these people instead of erasing them.

In the Biblical parable, while the prodigal son was off living life, the father’s other son remained with him. He worked hard in the fields, doing what was expected of him. When he sees how his father treats his brother upon his return, he grows angry and confronts him. His father tries to explain, but in the Bible it’s not clear whether either the two sons or the son and his father ever reconcile. Similarly, some Nigerians are, understandably, not thrilled with the presence of a burgeoning new elite. Life is already difficult enough: they are facing a struggling economy, mass unemployment, little opportunity, and now a new set of people appear and make their life harder, even if it is inadvertently.

The rising resentment is palpable: snide comments about people with accents or foreign degrees, the questions about whether or not returnees are running from something, the law or failure. If you’re a returnee and you’re yet to feel any of this then you haven’t been paying attention—and you should. So then what’s the solution?

I guess it’s a cop-out to say I don’t know, but I don’t. As minorities in our home countries, we are constantly asking people to check their privilege, as we should and as they should. As a black woman existing in the world, I never thought I’d be in a position where I have to check mine, but as a returnee living in Nigeria, I realize I do.

__________________________________

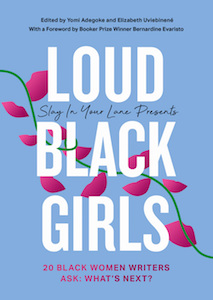

From Loud Black Girls: 20 Black Women Writers Ask: What’s Next?. Used with the permission of the publisher, Fourth Estate, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers. Copyright © 2021 by Yemisi Adegoke.

Yemisi Adegoke

Yemisi Adegoke is a former CNN Africa journalist and current BBC Africa reporter. She’s made several groundbreaking journalistic contributions, including participating in the Reading the Riots series in the Guardian in 2011 and unpacking the Fake News Crisis in Nigeria. A graduate of the Arthur L. Carter Institute of Journalism at New York University, Yemisi reports on the impact of misinformation in Africa, social issues and politics.