Long hair, broad shoulders, huge strides, and the number 10 on the winners’ white-and-blue shirts. World Cup ’78. Argentina on the podium.

The country went insane. Maybe it was, with everyone singing praises to the hippie running brazenly on the field. The newspapers showed people howling with pleasure. Each goal, an orgasm.

The papers only showed the ones howling with pleasure. The other howlers interested no one. In fact, they did not even exist. The others were desaparecidos brutally slaughtered offstage. The spotlight was solely for the golden boys and the military junta that had made the horror possible.

Since 1976, or perhaps even earlier, people had been kidnapped, tortured, assassinated. Everything was done in absolute silence. Our ears—and the world’s ears—were plugged, our lips sewn, our hands bound. The entirety of Argentina had been lobotomized.

Argentina campeón mundial

Argentina, rey del mundo

Campeones gran triunfo argentina

Hosannas and fanaticism. The headlines all the same.

The hippie, for the record, was Mario Kempes. His friends and enemies called him el matador. Goals and orgasms. Officially, that’s how it was. For the soldiers, the press, foreigners. The other howlers didn’t count. They weren’t official. Foreigners wanted the folklore. The press, heart-pounding excitement. The soldiers, laurel wreaths. Self-congratulation and champagne. A shimmering cup and sharp teeth. Orgasms in technicolor. That World Cup was the first one not shown in black-and-white.

Legend has it that in the first half Kempes was making an effort, but he didn’t score. He sweated, panted, swore, but didn’t score. He was dynamic like few others. On the field, he was king. But he didn’t score. The whims of destiny denied him glory among strikers. The soldiers didn’t like his restraint. Restraint could negate their glory, that same glory with which they wanted to deaden the conscience of us Argentinians. It was an act, a miserable conceit. They pretended to be good and we, on the other hand, pretended to believe in an Argentina that was by then a falsehood. But without Kempes’s goals, the scaffolding threatened to collapse. It was up to soccer to do something. It was soccer’s task. With crosses, shots on goal, extraordinary saves, it had to hide the heinous crimes the junta was committing against the sensible part of the country. The white-and-blue team was under pressure. There were veiled threats. Menotti—the coach of Argentina ’78—had what sports journalists called a stroke of genius. “We’ve got to be more superstitious. You can’t win without a pinch of magic.” He ordered the future matador to shave his famous handlebar moustache. Smooth as a maiden, Kempes took to the field against Poland. It was at the Gigante de Arroyito, a stadium that felt like home. He scored a brace. And for the rest of that World Cup he didn’t stop until the end.

When Kempes scarred Poland with that double goal, I’d been out of Buenos Aires for months. I was able to get away.

Many Argentinians rejoiced with the team. Their dutiful orgasms had the trademark of a military government and the blessing of Kempes and Menotti. The state needed imbeciles, and for that they’d put on that sideshow of a championship. Money flowed and blemishes were concealed, like the people who disappeared. Like my brother Ernesto.

Ernesto is now a number. He had a face, hair, beautiful hands. He laughed, sucking up air like a century-old combustion engine. He was a good boy. Better than me. And now he is a number on a list of thirty-thousand desaparecidos who never came home. We didn’t recover his body. To this day they’ve unearthed only twenty-thousand human scraps, but none belonged to Ernesto. I wonder how many decayed without the comfort of a grave.

So many disappeared, so many dead, so many in exile. The country’s finest, most principled citizens were hard-hit. Along with those boys, girls, friends, new mothers, union workers, priests, and intellectuals, the whole country had disappeared. We were all desaparecidos. We couldn’t speak, we couldn’t discuss, we couldn’t breathe. We could risk the same fate as our husbands and wives, our brothers and sisters and parents and neighbors. Everything was controlled and, out of fear, little by little, everyone began erasing themselves.

In those years the newspapers declared:

Guerilla Efforts Truncated

Eight More Extremists Mowed Down in La Plata

Insurgency Suffers Blows

The violent language of the press chilled my blood. I missed the word “kill.” I thought it warmer and more considerate than the words journalists used more frequently. I hated the words “mowed down,” for example. It seemed to suggest the human being’s desecration. It didn’t only imply the taking of life, but dehumanization. It was too much, superfluous. There wasn’t a headline that didn’t abuse words. Everything was a mowing down of subversives all across the country, 13 in Buenos Aires, 18 in Tucumán, 22 in Córdoba. We accepted the news bulletins of death as though it were banal bureaucracy. We had a high dosage of fatalism, some impassivity even, which was ultimately the other face of fear. We were so terrorized that indolence seemed to be the only form of resistance against barbarism. It isn’t so bad, the quiet life. A lot happens to others that doesn’t happen to me. And it followed that, without a shot fired, thousands of people were disappeared.

The people rejoiced for Kempes, the hippie matador, and perhaps in that same moment, they were attaching electrodes to your uncle’s ass to make him speak. What then?

They rejoiced for Kempes, the matador. A nickname in poor taste.

–Translated from the Italian by Aaron Robertson

__________________________________

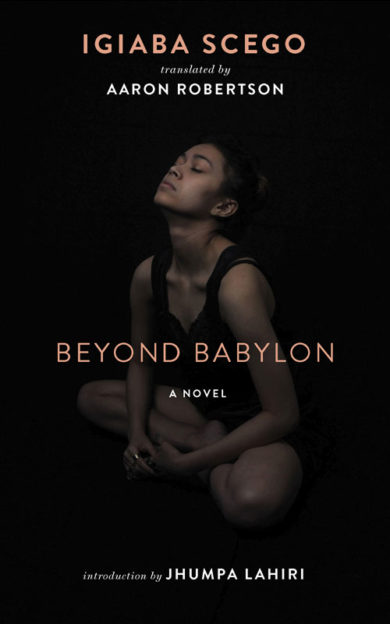

From Beyond Babylon by Igiaba Scego. Used with the permission of Two Lines Press. Translation copyright © 2019 by Aaron Robertson.