Between Two Istanbuls: Telling Stories of a Place That No Longer Exists

Kenan Orhan Explores the Intersection of Memory, Identity and Self-Imposed Exile

Growing up, I spent many summers visiting family in Istanbul: a mess of close and distant relatives, twenty of us piled into a two-bedroom apartment. The city exists in my mind as a kaleidoscope of enchanting memories—tea and pistachio ice cream at cafes tucked into peaceful inlets; fishermen with their spindly poles reaching down from Galata Bridge; the briny slap of the wind on the ferry; enormous tankers sliding through the strait; the smell of döner grilling through an open window.

But these memories are fading. When I began writing The Renovation it had been a decade since I saw the city with my own eyes, and I was losing it out from under me. We hadn’t been back to Istanbul since the Gezi Park protests, a watershed moment in modern Turkish history that heralded my family’s own unfortunate watershed. In 2013, millions across the country protested against the government, and though clashes with police ended brutally for the protestors, they continued through the summer. On June 2 almost 3 million protestors took to the streets in Istanbul alone, about the entire metro population of Denver.

My grandmother lived through the 1955 Istanbul Pogrom. My mother grew up during the political turmoil of the 70s when you could get shot for being in the wrong student union. They figured another bout of violence was coming and in a way they were right. Gezi gave way to crackdowns and an administrative witch hunt that saw thousands of academics, judges, journalists, lawyers, and civil servants jailed. Then a slew of terrorist attacks and bombing swept Turkey. In 2016, six occurred in Istanbul. That same year, a failed coup-attempt against President Erdoğan saw his regime gain massive public support which he quickly turned into a nationwide purge that, to date, saw over 80,000 detained, and another 150,000 fired—a not-insignificant portion of them simply for being Kurdish. Meanwhile curfews and military patrols became routine life in eastern Turkey.

Turkey feels like it is coming apart at the seams, which only amplifies this sense in the socket of my heart that I am losing a part of myself.

Relatives started suggesting I wait for Erdoğan to leave office before visiting. As I published more and more stories, they said my writing was inflammatory and would land me in jail (you can be jailed in Turkey for a bad joke). A little bit of this is over-cautiousness—we are, genetically, an anxious family. After all, as bumbling as I view the Turkish authorities, how could they possibly recognize me? As illiterate as they must be, how could they have read my collection?

*

This severance from Turkey has created a phantom limb experience for me and my brothers. We were raised rather carelessly with regard to our cultural inheritance, I suspect in part due to my mother’s family’s adept work at assimilating after immigrating. Our Turkishness was manifest in small and decontextualized rituals that could hardly pass as some ‘authentic’ experience. For us, being Turkish only happened when we were in Turkey (somewhat ironic given our rudimentary language skills). Over time we conflated these trips with self-discovery, an archeological act of digging up our identities. Turkey feels like it is coming apart at the seams, which only amplifies this sense in the socket of my heart that I am losing a part of myself. I haven’t been able to create new memories to shore up the old ones. My Turkishness, my experience of Turkey, my relationships with friends and relatives, are stunted, trapped in the past. As these memories of Istanbul deteriorate and corrode, I find myself standing on uneven ground, desirous, so desirous to return, but when?

I poured this expectation into Erdoğan’s presidency: as soon as he was out, as soon as his reign ended, Turkey would, like the magic of a fairy godmother, shift overnight and become a new and magnificent country but so too would end my family’s self-imposed exile, the end of my distance from relatives, the end of an impossible spell of homesickness. I will go back to Istanbul and find myself revitalized, find all my happy memories and like some trick of film-editing they will be whole again, vibrant, with sound and color instead of fraying at the edges. I will see my cousins again, my aunts and uncle, and they will all be just as before. Those ten years now heavy as the midday sun would fall away, collapsing us into each other, collapsing me into all the missed moments. They will be bright and happy and our happiness will be infinite. The latest election was the most promising of all. The opposition was polling ahead of Erdoğan. The country felt unified in its grievances against the regime. I looked at plane tickets. I told my partner to start practicing Turkish. I told my aunts I missed them.

*

But the opposition did not win, even if they had, there was no return in store for me, or at least none like I fantasized. The political firebrand that was one cousin (who, last I saw him, was quoting de Beauvoir and Sartre) has grown up into a cautious doctor of philosophy, married now and quiet, scared of the regime. His mother, the dancing, cursing, haggling aunt is now an arthritic septuagenarian. She lives with my other aunt, her sister, whose spine is being swallowed by osteoporosis. The two of them stay home most nights in their shared flat, in bed early, no longer loud, no longer laughing. Another cousin, the son of my industrialist uncle, has given up regattas and the hedonist’s life for a position in his father’s company that is, like all companies in Turkey, faltering under the tremendous burden of an economy in tailspin. Though I still long to see my family, still feel full to the brim with love for them, we are now ten-year strangers. Would I recognize them?

It feels the city itself has conspired against me to make itself unknown and unrecognizable. At the heart of the Gezi Park protests was a stand against Erdoğan’s plans to convert one of the few remaining green spaces of Istanbul into a neo-Ottoman arcade, one of many development and construction programs initiated under the regime for the sake of the simulacrum of progress and development. Under Erdoğan, Istanbul and the rest of the country has seen a construction craze, with bridges, tunnels, plazas, malls, and roads going up seemingly overnight with little regard to the city’s cultural heritage. Everywhere, stretches of concrete and glass are unraveling the historic fabric and replacing the green spaces of the city.

Under a government that has shown time and again it couldn’t care less about the safety of its people, building codes are evaded and safety violations go unreported resulting in exacerbated natural disasters, constant calamity at Soma and other mines and industrial centers across the country, and botched restoration projects for historical sites. An enormous new airport welcomes millions of visitors to Istanbul every year. Yavuz Sultan Selim bridge now connects the norther end of the strait. The Ayasofya has been converted back into a mosque. Kız Kulesi appears to have been dismantled and rebuilt. Galata Tower was “renovated” with jackhammers. Ancient mosaics have been restored into laughable deformities of their previous selves.

Perhaps most grotesquely, construction officially began on the Istanbul canal (what is essentially Bosporus 2) west of the strait that will greatly increase geological risks for the city in what has to be one of the regime’s greatest boondoggles. Sea snot has invaded the Aegean and killed off dozens of species in the Marmara. Fresh caught fish will be a thing of the past in Istanbul restaurants. Elsewhere, lakes are drying up, and dams are flooding millennia-old villages and historic sites. The very names of things throughout the country are shifting, becoming a state-sanctioned act of collective memory to further entrench the regime in the fabric of the country so that Erdoğan’s legacy will be his synthesis of the state into the individual.

The Istanbul I always dreamed of returning to is not just a fabrication of memory but something clouded completely by a political naivety.

Everything, even my own history seems to be changed under Erdoğan. I have two photos I revisit often, from my last trip to Istanbul. They are both taken at the same place, a café patio in the hills overlooking the Bosporus, one facing the water, the other recording the faces of all the relatives there with me. It was a beautiful view, and everything from the cocktail glasses to the breeze felt delicate. I can’t remember the name of the place, and have spent hours on Google maps trying to place it exactly but I can’t find the shoreline in the picture, I can’t seem to pinpoint the inlet in the background. Not only does it not to exist, but the way the skyline is, with certain palaces here and a bridge there, the whole image seems to be impossible.

What should happen to the rest of my golden memories when I alight from the plane and take a taxi into the city and down the road that runs beside Rumelihisarı? They are brittle and saccharine like candy floss. How could they survive these stark new truths outside the safety of my mind. Will they dissolve and leave me hollow of the Istanbul that has felt like homesickness? Will they shatter into a thousand pieces, every one of them a tomb?

The Istanbul I always dreamed of returning to is not just a fabrication of memory but something clouded completely by a political naivety. The flashpoint moment of Gezi Park, the terrorist attacks, the resumed conflict with Kurdish separatists, the schism between Gülen and Erdoğan, all of this was outside my glittery bubble of understanding. Without them, Istanbul was only hip dance clubs, seaside restaurants, chic clothing stores, cafés with patios garbed in white tablecloths, dondurma, raki, baklava, pleasure cruises through the Bosporus, a large and roarously laughing family—all acted as a thin film to obscuring the country’s political realities. It was easy, having no stake in the consequences, to think of Turkey as a place of infinite joy and stars twinkling in the sea.

But this is not and has never been the city. I have deluded myself for ten years that ousting Erdoğan, watching him lose an election, would somehow give me back everything I missed out on. It would give me back my great-grandparents’ funerals, my cousins’ weddings, the birth of their children. This place that has obsessed my dreams and left me hollowed out at the foot of its immense beauty is only a place of the past. Like childhood’s magic frontiers, there is no way to travel back once you have left. What makes this run-off so bitter is that it took this stutter-step for me foolishly, childishly, finally to realize no amount of votes, no amount of party alliances, no amount of wishing will return the last ten years to Turkey, to my relatives, to me.

__________________________________

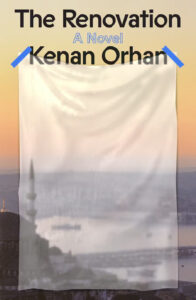

The Renovation by Kenan Orhan is available from Farrar, Straus and Giroux, a division of Macmillan.

Kenan Orhan

Kenan Orhan’s debut collection, I Am My Country: And Other Stories, was a finalist for the PEN/Robert W. Bingham Prize and was long-listed for the Story Prize. His fiction appears in The Atlantic, The Paris Review, The Common, The Massachusetts Review, and elsewhere and has been anthologized in The O. Henry Prize Stories and The Best American Short Stories. The Renovation is his first novel.