Between Myth and Modernity: On Persian Stories, Identity, and the US-Iran Divide

Ryan Bani Tahmaseb Considers the Enduring Wisdom of Iranian Myths

In one of the most tragic stories from Persian mythology, the legendary warrior Rostam unknowingly kills his own son, Sohrab, in battle. Sohrab had grown up estranged from his father, and when the two finally meet, it’s as enemies. Neither knows the other’s identity until it’s too late.

It’s a tragedy built on misrecognition and the failure to truly see the human being across the battlefield.

Earlier this summer, when tensions escalated once again between Iran and the United States, I began thinking about this particular myth. Both nations project strength while speaking in threats, each certain of its own moral superiority. Yet neither one truly sees the other: its history, its culture, its people.

For me, there’s a profound sadness in the loss of that possibility for him—to revisit, or maybe retell, the story of his own origin.

My father, who was born in Tehran, moved to the U.S. with his parents and siblings when he was in elementary school—well before the so-called Iranian Revolution. His father, my grandfather, was an international businessman who leveraged his American friends’ connections.

They moved to Salt Lake City, Utah, of all places, where the geography and climate were similar to Tehran’s. They moved because my grandfather was inspired by the loud, popular myth that the United States is the greatest country in the world. They wanted to live inside that myth, too.

My father, who loves to travel, retired a few years after our first child was born and has been bouncing around the country—and to a lesser extent, the world—ever since. But it wasn’t until the past year or so that he began telling me, for the first time, that he wanted to visit the country where he was born.

I was thrilled for him—the Iranian-American man who’d once been the Iranian-American boy who spoke only Persian, no English, and somehow stumbled, then pushed, then carved his way forward, as immigrants do. But last month, during the “12-Day War” between Israel and Iran, when the U.S. bombed three Iranian nuclear sites, the possibility of returning to his homeland was obliterated, too.

Not that it was a perfectly safe option before, given the aggressive and violent rule of the Islamic Republic, but now, with this unprecedented escalation of violence by the US, it’s not really an option at all.

For me, there’s a profound sadness in the loss of that possibility for him—to revisit, or maybe retell, the story of his own origin.

I understand that pull.

I’ve been writing stories for a younger version of myself who didn’t see any trace of that Persian part of me reflected anywhere.

As a writer, over the last decade, I’ve found myself for the first time digging into my cultural heritage—the Persian part of myself that, throughout my childhood, I actively disregarded and disliked. The part that gave me a last name no one could pronounce. The part that led my 10th-grade history teacher, on 9/11, to pull me aside and ask if I was worried about the coming American backlash toward people of Middle Eastern descent like me. In friends calling me a terrorist in the aftermath, and me laughing every time because I felt I was in on the joke. (Maybe I was.) The same friends who dubbed the truly very American sandwiches my father packed for my lunch “Persian delights.” And the part that caused me to be “randomly” selected for extra security checks before flights for years afterward.

Because it wasn’t until I started writing that I started taking my cultural heritage seriously. This wasn’t intentional. The stories I found myself wanting to write required learning more about Iranian history and culture—and my personal connection to both.

So, in a way, I’ve been searching for my own origin myth by writing books for children and teens that explore and incorporate elements of Persian culture. By extension, I’ve been writing stories for a younger version of myself who didn’t see any trace of that Persian part of me reflected anywhere.

My next book, written for middle-grade readers, is a collection of retellings and remixes of stories from Persian mythology. While researching it—which involved studying the Shahnameh (the Persian “Book of Kings” and Iran’s national epic), the Zoroastrian holy texts of the Avesta, and retellings of Iranian oral traditions—my attempt to better understand, or perhaps to create, a personal myth of origin became intertwined with the cultural stories of Iran.

Now, about a year later, with the book set to be published at a time when the authoritarian leaders of both the U.S. and Iran seem more invested in national myths of their own making, I find myself in a disoriented mental space, where personal, cultural, and national myths have become an existential tangle of chaos and disorder.

And yet, amid all this chaos and disorder, it’s the myths of ancient Persia—those enchanted, sometimes violent, auspicious stories—that hold the advantage of time-tested wisdom. They come without the self-righteous navel-gazing or false pride that often accompany personal or national quests to impose meaning.

These ancient stories have endured, sometimes only in fragments, because more than any narratives we try to tell ourselves today, they offer a richer, more nuanced understanding of who we are, why we’re here, and where we might be headed.

Persian myths and legends challenge our modern ideas—and ideals—about strength and national pride, and taken together, they ultimately point toward the hard-won establishment of peace and order.

The ancient mythologies of the world have wisdom in spades—and we could certainly use that now.

Rostam, one of the strongest and bravest heroes of Persia, kills his own son, Sohrab, because Sohrab fought for Turan, an enemy nation. And when Rostam realizes what he’s done, he’s full of grief and regret for the rest of his days.

Anahita, the guardian goddess of war and the waters, is constantly beseeched by all those on Earth—human and otherwise, good and evil—for favors and protection. With great wisdom, she responds with generosity to all who have noble goals, moral purity, and who fight for justice.

Jamshid, a king who does much good in his lifetime, ultimately loses his humility and thinks of himself as a god—leading the Persian people to suffer at his hands and completely lose faith in him. He is overthrown by Zahak, the evil king with serpents growing from both of his shoulders—placed there by Ahriman, ruler of the Underworld—who terrorized the Persian people by feeding the brains of boys to his snakes.

The Simurgh—a dog-headed, peacock-bodied, lion-clawed, rainbow-colored bird—serves as a wild, wise mother figure to human heroes and leaders, swooping down from her nest atop the mystical Mount Alborz whenever she’s most needed, to restore peace and protect those most in need.

Ahura Mazda, the creator god, at the end of the world, destroys Ahriman and all evil, and all the souls of the world are purified and reunited and together for all eternity.

After all, we have a choice in the stories we listen to, the stories we choose to believe.

Again and again, these myths show that power without understanding or restraint leads to disaster, that violence spirals into more violence, and that order only comes through hard-earned wisdom and the ongoing, difficult work of peacemaking.

The ancient mythologies of the world have wisdom in spades—and we could certainly use that now. As Americans—a nation of immigrants like my father—we’d benefit from dropping the national myth of being the best country on earth, and instead getting more curious about the people our leaders have demonized, like Iranians. Learning more about the oppressed people who live there, and their history and culture, including their mythology, is vital—because it’s always been stories, especially myths (those stories we can’t help but tell again and again), that help us better understand ourselves—and, ultimately, each other.

In the process, we might even see our own increasingly oppressive regime reflected in theirs. We might ignore the bluster of both regimes and hear the ancient rhythm of peace, because it’s there in the stories. After all, we have a choice in the stories we listen to, the stories we choose to believe.

Ancient myths—lest we forget—may not be true in the literal sense, but emotionally, spiritually, they’re truer than anything we read or see or hear in the media. And we can be reminded that authoritarian rulers always fall, good triumphs over evil, peace ultimately prevails, and wisdom is what gets us there.

____________________________

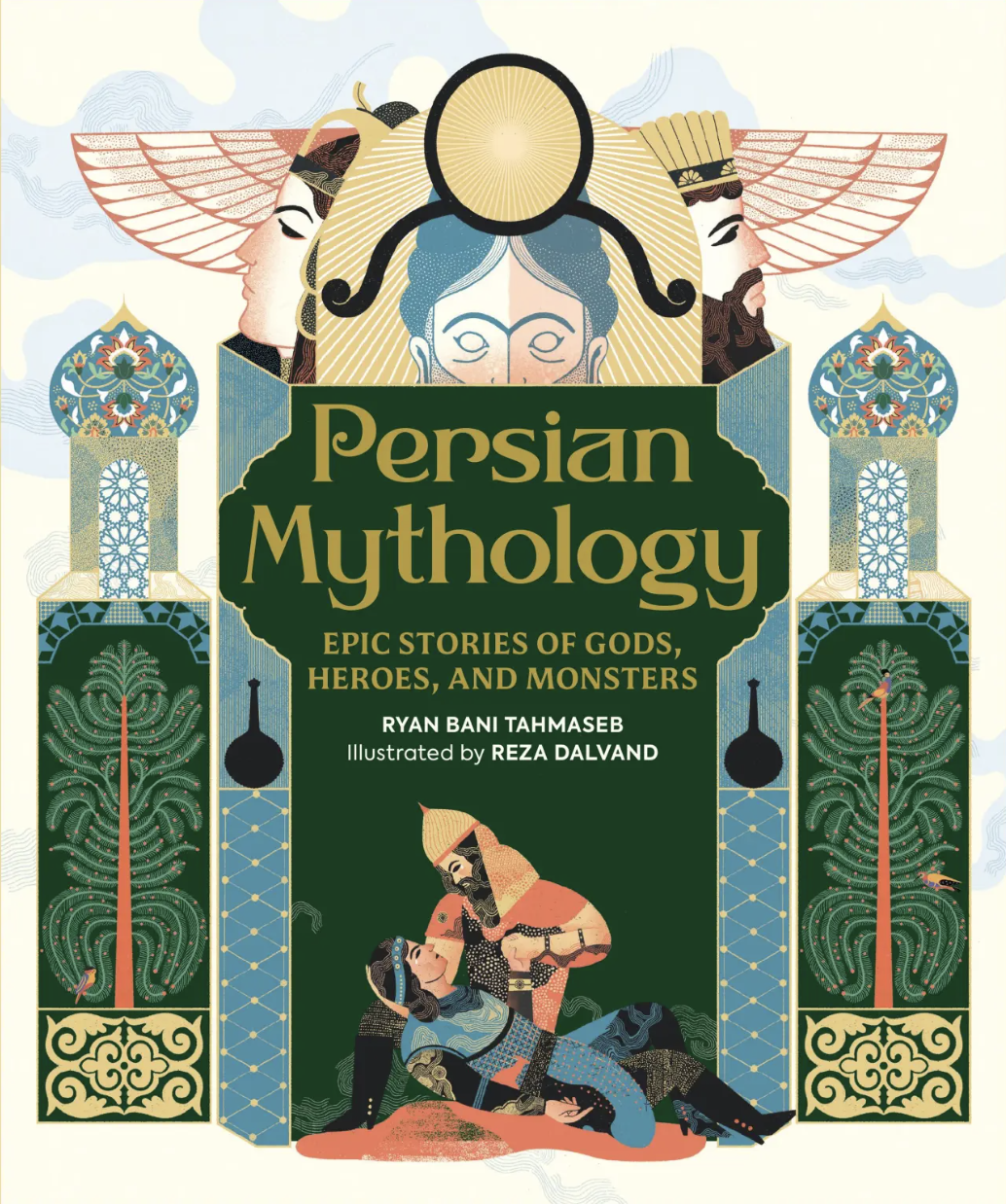

Persian Mythology, by Ryan Bani Tahmaseb, with illustrations by Reza Dalvand, is available for pre-order from Running Press.

Ryan Bani Tahmaseb

Ryan Bani Tahmaseb is an author, educator, and avowed Persian mythology superfan. His debut picture book, Rostam’s Picture-Day Pusteen, based on his father’s experience as a young Iranian-American immigrant, was published by Charlesbridge. His first professional book for educators, The 21st Century School Library, which details how teachers and administrators can better utilize their school library and librarian, was published in 2022 by John Catt Educational. His writing has also appeared in publications such as Education Week and the Carolina Quarterly. He lives in York, ME with his wife and two young children.