Between Desirability and Possibility: On the Beauty of the Aging Female Body

Darcey Steinke Considers the Work of Linda Troeller and the Liberatory Potential of the Self-Portrait

“The body,” Simone de Beauvoir proposed, “is not a thing but a situation.” But photographer Linda Troeller makes clear in her self-portraits that the body is both thing and situation. Female self-scrutiny, which Troeller wields relentlessly, exposes her body as diaphanous, more spirit then flesh, but also, as in the photograph of her headless body in a red corset, manifestly material. In our corporeal form, we are pinned to the earth. Troeller’s aged body, while fit, is also larva-like in the stiff corset, the lingerie as much desexualized bandage as clichéd conduit to desire.

Can lingerie be worn ironically? Now that we understand that biological sex does not lead directly to social destiny, but is rather constructed, I have to wonder why a body, an aged body, a wise body, would freely take on such a narrow definition. Troeller makes good use of my apprehension, of the tension between her own body’s desirability and the possibility of unbracketed female expression. There is in these images a sly revolt. “Hiding,” Troeller has said, “is a restorative act.”

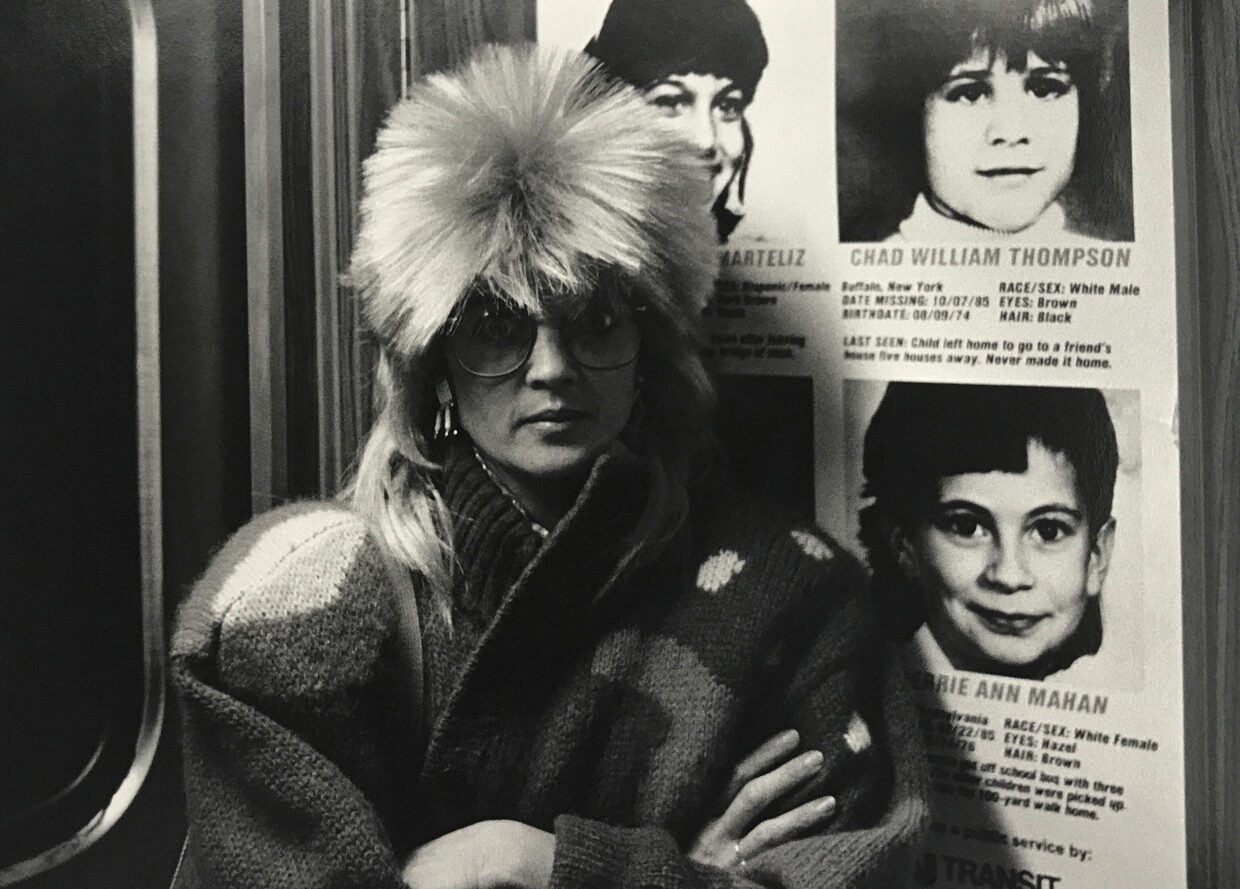

Self-Portrait, Lost Children, 1986. © Linda Troeller, 2024 from the book Sex. Death. Transcendence. Courtesy of TBW Books.

Self-Portrait, Lost Children, 1986. © Linda Troeller, 2024 from the book Sex. Death. Transcendence. Courtesy of TBW Books.

Illness and damage, as well as age, have been used to disrupt the way we’re taught to view the female nude—namely by rating a woman’s desirability rather than seeing her as in possession of her own self. In Troeller’s 1994 self-portrait in a steam room, recuperating from a car accident, the sexuality of her body is held in tension with her neck brace. Frida Kahlo also portrayed her body as broken, bloody, punctured, not as in earlier depictions of saints—the broken body as conduit to God—but as a way to block the judgment that objectivizes women. Hannah Wilke’s Intra-Venus (1992–93) used this same strategy, showing the artist’s body suffering from the lymphoma that would eventually kill her. The pun Intra-Venus locates the work in relation to two millennia of idealized goddess sculptures and paintings.

In her sickbed, Wilke positioned herself reclining like nudes in historical paintings, albeit bandaged and with skin discolored from chemotherapy. Troeller extends Kahlo’s and Wilke’s idea of intimacy with the authentic female body. Photos of her in curlers, in facial masks, or pulling at her chin hairs elevate and universalize everyday female rituals. “If women have failed to make ‘universal’ art because we’re trapped within the ‘personal,’” Wilke wrote, “why not universalize the ‘personal’ and make it the subject of art.”

Self-Portrait, Hippocrates Health Center, FL 2009. © Linda Troeller, 2024 from the book Sex. Death. Transcendence. Courtesy of TBW Books.

Self-Portrait, Hippocrates Health Center, FL 2009. © Linda Troeller, 2024 from the book Sex. Death. Transcendence. Courtesy of TBW Books.

In one 2019 photo Troeller looks down at the camera, wrinkled and spotted but also bifurcated by a ray of multicolored, prismatic light. In many of these recent pictures, sexuality is split off from fertility, motherhood, youth, and their traditional demarcations. Desire in older women has yet to be culturally assimilated. We are told we are gross, unlovable. The root of this negation is not, as has been assumed, male repulsion for old bodies but a form of control over our sexuality. “Sexual intercourse was particularly worrisome for European patriarchies,” writes Lynn Botelho in her essay “Old Women and Sex” (2000). “After the menopause, there could be no punishing pregnancies that served to publicly shame a wayward woman, nor legitimate children to further God’s plan.”

In many of these recent pictures, sexuality is split off from fertility, motherhood, youth, and their traditional demarcations.

After a 2016 house fire destroyed much of Troeller’s archive, the artist Carolee Schneemann wrote to tell her about her own fire: “Debris, ruins, disaster can present an unexpected, engrossing aesthetic.” Troeller’s photos in this volume move easily back and forth between her aging body and early self-portraits, the earliest ones taken when she was a smooth and supple twenty-four. Linear time, as well as categories of before and after, are disregarded. We are accustomed to seeing the ramshackle house in the “before” photo and the restored, pristine dwelling in the “after.” But, I wonder, might the “before” be a young body, and the “after” an old one? Or is the “before” the older body, finally able to encompass the past, the younger self within?

Self-Portrait, Job Interview Chicago Art Institute, 1975. © Linda Troeller, 2024 from the book Sex. Death. Transcendence. Courtesy of TBW Books.

Self-Portrait, Job Interview Chicago Art Institute, 1975. © Linda Troeller, 2024 from the book Sex. Death. Transcendence. Courtesy of TBW Books.

Aging is often portrayed as a terrible tragedy for women. “In me,” Sylvia Plath wrote in her poem “Mirror” (1965), “she has drowned a young girl, and in me an old woman / Rises toward her day after day, like a terrible fish.” But do we have to kill our younger selves in order to become the matriarchal goddesses we are clearly meant to be? More violent but also somehow inspirational is the story of British suffragette Mary Richardson, who in 1914, to protest the arrest of fifty-six-year-old feminist leader Emmeline Pankhurst, smuggled a cleaver into London’s National Gallery and attacked Diego Velázquez’s Rokeby Venus (1647). “I have tried to destroy the picture of the most beautiful woman in mythological history,” wrote Richardson, “as a protest against the Government for destroying Mrs. Pankhurst, who is the most beautiful character in modern history.” Her slashes in the canvas could be read as wounds or scars—either way, they aimed to destroy a man-made ideal in order to bring the young and old feminine authentically together. “Justice,” Richardson continued, “is an element of beauty as much as color and outline on canvas.”

Self-Portrait, Gold Facial, 2010 NYC. © Linda Troeller, 2024 from the book Sex. Death. Transcendence. Courtesy of TBW Books.

Self-Portrait, Gold Facial, 2010 NYC. © Linda Troeller, 2024 from the book Sex. Death. Transcendence. Courtesy of TBW Books.

“I feel,” Georgia O’Keeffe wrote, “there is something unexplored about woman that only a woman can explore.” O’Keeffe encouraged the young camera-carrying Troeller during the latter’s 1970 residency at Ghost Ranch: “Go outside and see what the spirits tell you.” Several of Troeller’s early self-portraits indeed have ghostly qualities. One, of the artist in her twenties, shows her in a diaphanous white dress, flooded with light, her hair falling around her head and her eyes gazing heavenward in a manner most pre-Raphaelite.

In another, taken not long after, while the artist was in graduate school, Troeller floats in a long white gown over grass with the eerie aura of a supernatural being. Unlike Hallmark-card cherubs, angels, according to the Bible, are sexless, androgynous creatures, containing either both genders or neither. In a photo of Troeller in her thirties, she resembles Caravaggio’s cupid with her broad, beautiful features, curly auburn hair, and sensual, open mouth. Rather than an otherworldly message, both Troeller’s and Caravaggio’s cupids convey a comfort with human pleasure, not in the sky but on this Earth.

Self-Portrait, Halo-Mirror, 7AM 2020. © Linda Troeller, 2024 from the book Sex. Death. Transcendence. Courtesy of TBW Books.

Self-Portrait, Halo-Mirror, 7AM 2020. © Linda Troeller, 2024 from the book Sex. Death. Transcendence. Courtesy of TBW Books.

“I warn you,” wrote the painter Leonora Carrington, “I refuse to be an object.” An angel in statue form appears in a later Troeller self-portrait. The artist, now in her sixties, hides behind the figure. The similarities between stone and flesh are remarkable, but it’s clear that the angelic icon has been cast out—Troeller has separated herself from it, and in a “restorative act” stands behind her former avatar.

*

It’s impossible not to look for information about the artist in a self-portrait. While selfies usually show us beautiful and happy, Troeller’s face, particularly now, in her seventies, carries an almost sci-fi sense of molting transformation. Depictions of conventional religious subjects have declined since the Enlightenment, but what has survived is the transcendent body. Troeller’s work both exists inside this tradition and expands on it.

In another recent photo, the artist’s hair is pulled back, her face shimmers, and I read in her darkly made-up eyes a kind of power at the prospect of approaching oblivion. “The camera,” the artist has said, “the taking and the clicking, is almost like a response from within. That I will have another second here. I will be here longer.” Are we supernatural beings confined for a time to human form, or fleshy animals with delusions of immortality? Sex may give us a temporary respite, but only death, Troeller seems to say, will free us from our corporeality completely. Into what form, angelic or otherwise, remains our greatest mystery.

—Darcey Steinke

__________________________________

From Sex. Death. Transcendence. by Linda Troeller. Copyright © 2024. Available from TBW Books. Featured image above: “Self Portrait,” Syracuse University Dorm with Leica M3 Double Stroke, 1973. © Linda Troeller, 2024 from the book Sex. Death. Transcendence. Courtesy of TBW Books.

Darcey Steinke

Darcey Steinke is the author of multiple nonfiction and novels, including her most recent memoir, Flash Count Diary. Her work has been translated into ten languages, and her nonfiction has appeared in the New York Times, The Paris Review, Granta, among many others. She has taught at Columbia University School of the Arts, New York University, Princeton University, and the American University of Paris. She lives with her husband in Brooklyn, New York.