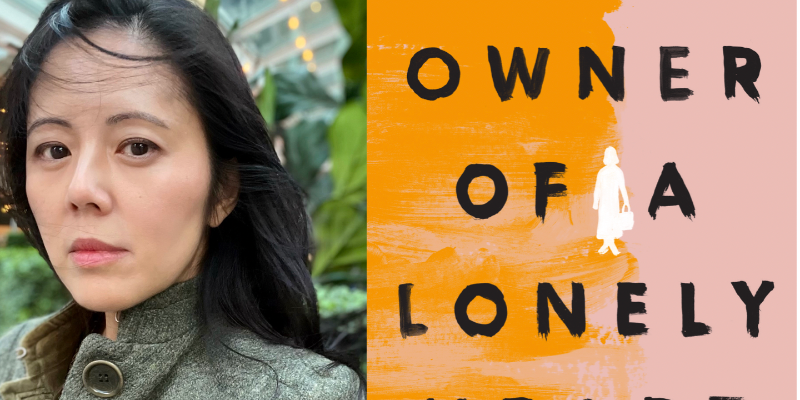

Beth Nguyen on Memoir, Mothering, and Refugeedom

In Conversation with Whitney Terrell and V.V. Ganeshananthan on Fiction/Non/Fiction

Novelist and nonfiction writer Beth Nguyen joins co-hosts V.V. Ganeshananthan and Whitney Terrell to talk about her new memoir, Owner of a Lonely Heart, which is about her separation from and connection to her mother. Nguyen explains how when she came to the U.S. as a refugee, her mother was left behind in Vietnam. She discusses how returning to scenes depicted in her previous memoir, Stealing Buddha’s Dinner, prompted her to reassess and revise her memories of her mother, including their eventual reunion. She also reflects on how becoming a parent herself has shifted her perspectives. She reads from Owner of a Lonely Heart, speaks about the rise in anti-Asian racism, and, finally, turns to the intersection between poetry and nonfiction.

Check out video excerpts from our interviews at Lit Hub’s Virtual Book Channel, Fiction/Non/Fiction’s YouTube Channel, and our website. This episode of the podcast was produced by Rachel Layton and Anne Kniggendorf.

*

From the episode:

V.V. Ganeshananthan: In the opening lines of Owner of a Lonely Heart you write, “Over the course of my life, I have known less than 24 hours with my mother. Here’s how those hours came to be and what happened in them.” And those lines are just immediately so gripping. The opening is incredible. When we think of family, we often think of togetherness.

And one of the reasons that this beginning is so gripping is because of its seeming incongruity. You’re frequently writing about separation, and sometimes even a lack of knowledge. So I wonder if you could talk a little bit about how the need to represent silence and separation in families influenced the shape of the book.

Beth Nguyen: Yeah, so I guess everything goes back to my origin story, which is that my family and I left Vietnam as refugees, the day before the fall of Saigon in 1975. Because I was a baby then, I have no memory of what happened, but I retain so many memories of what happened after. That is, what it was like to grow up in a refugee family and refugee household in the Midwest in the 1980s. Part of that story is that my mother stayed in Vietnam when the rest of us left, and I didn’t end up meeting her until I was 19 years old.

So the silences, the gaps, the separations in my family story, including all the ways in which we just never talked about my mother, because it was too difficult of a subject, all those all those things informed my thinking about what it meant to be a refugee in the United States, and how that word refugee is so often suffused with a sense of shame. So in this book Owner of a Lonely Heart, I was trying to deal with that as directly as possible. For me, that meant a lot of acknowledgment of those gaps and silences. So there are spatial gaps in the text, and a sort of direct confrontation of how things are remembered, what is just not even remembered at all, and what we don’t want to remember.

Whitney Terrell: At one point later in the book, after you reunited with your mother, you write that you sometimes have to remind yourself that you’re now both mothers. Could you talk about that a little bit more? What’s the relationship between mothering and the desire to be mothered?

BN: I feel like I’m still surprised all the time. Whenever I’m talking with my mother in Boston or, more often, when I’m talking with my stepmom, whom I call mom in real life, I’m always surprised that oh, wait a minute, Mom, I’m also a mom. Because for me, and I think maybe for a lot of people, our formative years are tied to a sense of understanding of who mom is or who dad is.

And so when that changed for me, when I became a mother, also, that involved just this huge shift in perspective, basically. When I stopped identifying with Ramona and started identifying with Ramona’s mother, that was the same sort of shift. It just meant being in more than one place at the same time and more than one person at the same time.

The reason why it was useful for me in this book was because it reminded me that shifting identities is part of what we do in writing all the time, especially in nonfiction writing. We think about who we are in terms of perspective, who we are now against who we were back then whether that was last week or 20 years ago, and how we’re always more than one person, more than one self at the same time.

I think that goes back to what Phillip Lopate calls “delta perspective,” which is something I teach a lot, the sense of acknowledging who we are in the moment now, writing who we were back then, and how we are to inhabit two perspectives, two selves, at the same time. And so every time we write the past, we’re always changing it a little because we become somebody else, like the mother I am now is a different mother than five years ago when my children were five years younger. And so it’s this constant sense of things always changing, which is very much part of what being a parent is.

VVG: So one of the interesting things about reading this book for me is that I had read your book Stealing Buddha’s Dinner, which is your previous memoir. What year did that come out, Beth?

BN: That was 15 years ago.

VVG: So, interestingly, there were actually scenes in Stealing Buddha’s Dinner that happened again in Owner of a Lonely Heart and, as a reader, it was fascinating to go back to the scenes again. I mean, some of the going back happens within each book, like, “I’m not sure of how this memory happened, or this is how this person told this memory. This is how I remembered it, but it turned out to be wrong.”

Then 15 years later, you’re returning to some of that same material. So what was that like to go back? Did you look at Stealing Buddha’s Dinner again? I was reading it this morning in preparation for our chat and was sort of like, Whoa! I should have known. Also, it’s presented differently, but then also certain aspects are, of course, the same.

BN: Right, so that was one of the hardest things for me, having to reread my own work. I don’t think any writer wants to do that. But I had to reread that book, because I had to remember how I remembered things. And therefore, confront what I was changing my mind about, or how I saw things differently. I think that the whole process of writing this book, Owner of a Lonely Heart, was part of this ongoing reckoning with myself about how the past is not static, that it changes all the time because we keep changing as people.

And that is also very much part of the writing process, the rethinking. Giving ourselves permission to change our minds and change our perspective, I think is very difficult, but also something that we need to do for ourselves, not just as writers, but as people. To say, you know, what I felt like once, that’s what I believed back then. Maybe I believe something else now because I know more now. And that’s good. I mean, if we thought exactly the same thing 15 years ago as we do now… I would be worried if I didn’t want to change anything that I wrote 15 years ago.

I think all of us, if we look back at something we wrote even a week ago, we want to change and revise it because we’re constantly questioning what we were thinking, especially in nonfiction. Memoir is not about transcription, it’s not an absolute “this is how it happened” kind of document. It is informed by subjectivity. It is made up of uncertainty. It is all about constant inquiry. That was something I was trying to embrace very much in this book.

VVG: Can you give us any specific example of something that you portrayed one way in Stealing Buddha’s Dinner, and you found that you had shifted for this book?

BN: One thing I talked about in this book was the way I remembered meeting my mother for the first time when I was 19 years old. And I realized that somewhere over these years, I had started to remember it wrong. Like I made the memory better than it actually was. My mind wanted to make it smoother. The actual way I met her was a little less interesting. There were some logistical complications involved. But my mind wanted to skip over that and just make it a little bit more narratively smooth and pretty and cinematic.

But in actual life, it wasn’t quite like that. And when I realized that, in rereading Stealing Buddha’s Dinner and thinking about what my mind had wanted, and what my former self had written, and what had actually been and talking to my sister, I was like, “Wow, what’s wrong with me?” Which is the essential question, I think, of so much nonfiction writing. “What’s wrong with me? How did I get to be like this?” I had to wonder and think about why we want to depict the past in the way we do. And what are our goals, actually, what are our desires in the act of depiction?

*

Owner of a Lonely Heart • Stealing Buddha’s Dinner • Pioneer Girl • Short Girls: A Novel

Others:

Phillip Lopate • “Tracing a tragedy: How hundreds of migrants drowned on Greece’s watch,” The Washington Post • “Missing Titanic Submersible ‘Catastrophic Implosion’ Likely Killed 5 Aboard Submersible,” The New York Times • “Trump Defends Using ‘Chinese Virus’ Label, Ignoring Growing Criticism,” The New York Times, March 18, 2020 • “How violence against Asian Americans has grown and how to stop it, according to activists,” by Frances Kai-Hwa Wang, April 11, 2022, PBS NewsHour • Asian American Month • Miss Saigon by Claude-Michel Shöenberg and Alain Boublil • The Phantom of the Opera by Andrew Lloyd Webber • Platoon, directed by Oliver Stone • Full Metal Jacket, directed by Stanley Kubrick • The Age of Innocence by Edith Wharton • “America Ruined My Name For Me: So I Chose A New One” by Beth Nguyen, The New Yorker • Fiction/Non/Fiction Season 2, Episode 7: Bich Minh Nguyen on the Refugee Experience of Holiday Narratives

Fiction Non Fiction

Hosted by Whitney Terrell and V.V. Ganeshananthan, Fiction/Non/Fiction interprets current events through the lens of literature, and features conversations with writers of all stripes, from novelists and poets to journalists and essayists.