Behind the Scenes at Andy Warhol’s First Big Bash in “Vacant, Vacuous Hollywood”

Mark Rozzo on the Artist's First Trip to LA, with Dennis Hopper and Brooke Hayward

Irving Blum was organizing a second Ferus Gallery show for Andy Warhol, scheduled for September, that would showcase the new silver silk-screen works that Dennis Hopper and Brooke Hayward had seen at the firehouse studio. They fell into two series—one depicting Elizabeth Taylor in a publicity shot from Butterfield 8, the other Elvis Presley in a gunslinger pose from his 1960 film Flaming Star.

Here were two celebrity icons of such stature that their very images projected the concept of fame—ultra Pop. The subjects, both friends of Dennis’s from the 1950s, were tailor-made for a show in LA, and Blum assured Warhol that there would be great interest from collectors and the public alike.

Learning that Warhol planned to travel west for the opening, Dennis and Brooke decided to help launch the show with a bash at 1712 North Crescent Heights—Warhol’s West Coast coming-out party. It would also be a coming-out party for the house.

Brooke continued her station-wagon safari, now with extra impetus. A Victorian-era revolving Richardson’s spool silk thread cabinet, an eight-foot-tall 1890s Apéritif Mugnier advertising poster by Jules Chéret, circus posters, an old-fashioned pipe organ, a giant plastic Coke bottle that looked like a free-standing sculpture, a smattering of Mexican folk art, a disco ball and Fresnel lights for the foyer—it is impossible to know precisely when such artifacts arrived at 1712, but Brooke and Dennis were pushing further to create an atmosphere worthy of their artist friend.

Dennis, as besotted as ever with Foster & Kleiser, hit upon the idea of papering the downstairs bathroom with billboards. They were, after all, LA’s native art. “To deprive the city of them,” the British architectural historian Reyner Banham noted, “would be like depriving San Gimignano of its towers or the City of London of its Wren steeples.” Hand-painted billboards would take too long to produce, Dennis was told, so they settled on lithographed ones, which were cut this way and that in order to fit on the walls. Inside the snug bathroom, the Brobdingnagian scale of the sliced-up imagery—including a woman with a Crest-worthy smile and a guy holding a hot dog—had a mesmerizing effect: you felt as though you were stepping into a James Rosenquist painting every time you had to pee. (“Brooke hated it!” Blum said; Brooke insisted that she thought it was “brilliant.”)

They decided it would be a cocktail party, but there still had to be food. Dennis floated the idea of a New York-style hot dog vendor. Brooke called around and found a guy with a cart who was willing to park on North Crescent Heights and serve chili dogs. Invites went out to friends in the art scene and in Hollywood, guaranteeing the kind of “movie star party” that Warhol dreamed about.

It was set for Sunday, September 29, the night before the opening at Ferus. Wallace Berman’s RSVP transformed the invitation into a borderline pornographic postcard, thanks to a cutout image of a pair of couples going at it that he glued on. That saucy bit of Berman mail art joined the growing collection at 1712.

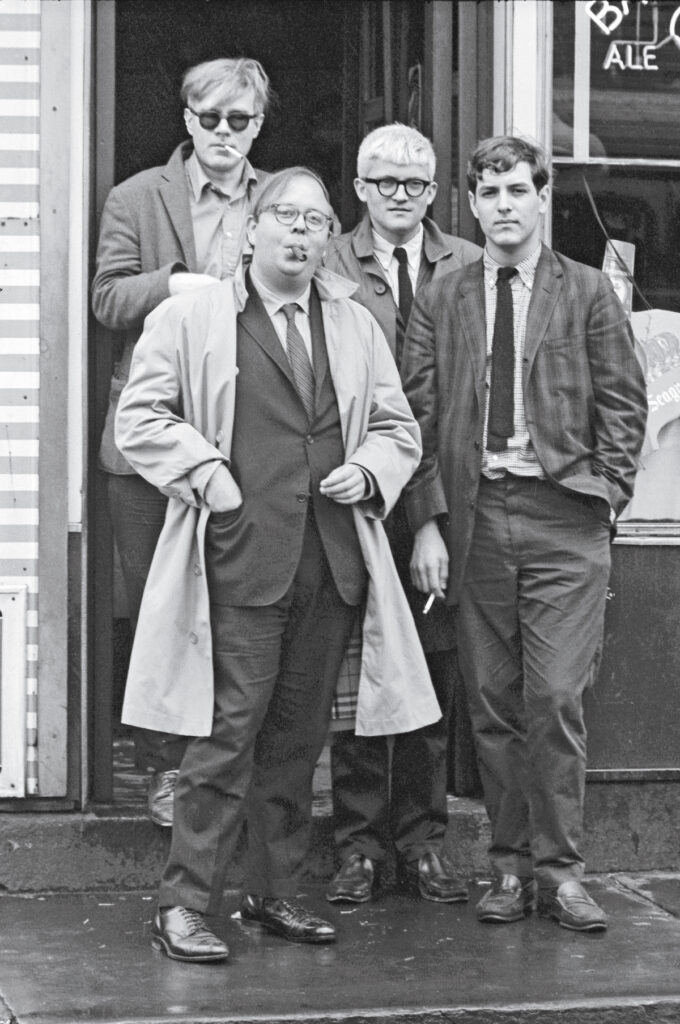

Dennis Hopper/Hopper Art Trust: “Shadowy devil’s head”: Dennis’s photograph of Andy Warhol at the Sign of the Dove restaurant, New York, June 1963.

Dennis Hopper/Hopper Art Trust: “Shadowy devil’s head”: Dennis’s photograph of Andy Warhol at the Sign of the Dove restaurant, New York, June 1963.

Warhol had never been west of his native Pittsburgh. “Vacant, vacuous Hollywood,” he said, “was everything I ever wanted to mold my life into.” He decided to road trip to Los Angeles with his assistant, Gerard Malanga, who had begun working with Warhol the day of The Defenders shoot; the beefily handsome painter Wynn Chamberlain, who conveniently owned a Ford Falcon station wagon; and Taylor Mead, a native Michigander, recovering Merrill Lynch stockbroker, and droll provocateur who bore a resemblance to Droopy Dog. Having been introduced to Warhol by Geldzahler, Mead thought the artist was America’s answer to Voltaire.

It took a few days to traverse the continent. “The farther West we drove, the more Pop everything looked on the highways,” Warhol noted. The Saturday before the party, they overnighted at the Sands Hotel in Palm Springs, and on Sunday they proceeded to Los Angeles. They cruised along Sunset Boulevard, which they found lined with Foster & Kleiser billboards and the kind of eye-grabbing signage—crazy parabolas, asters, and swooshes implanted with antic lettering and neon—that Tom Wolfe called “electro-graphic architecture.” Soaking it all up, Warhol said, “Oh, this is America.”

The travelers headed straight to 1712 North Crescent Heights, veering off Sunset and winding up into the hills. “It was like this invasion of creeps,” Chamberlain said of their entry into the scene that awaited them. Warhol and his motley entourage were hardly household names in 1963, and now they were in a surreal fun house crowded with Hollywood players who looked like living Pop Art—Sal Mineo, Russ Tamblyn, Dean Stockwell, Bobby Walker, Peter Fonda (who struck Warhol as a “preppy mathematician”), and the It couple of the moment, Suzanne Pleshette and Troy Donahue.

Warhol had used Donahue as a subject for his silk-screen artwork and even a T-shirt, one of which Blum had worn in the photo that had announced Warhol’s Ferus show. “Andy and I were both stargazing,” Malanga said. “I was pretty awestruck being a kid coming from the Bronx and landing in Hollywood.”

Malanga, a twenty-year-old poet with pop-idol looks, hung out with Berman and Tony Bill while Warhol reconnected with Bengston and Blum, mixed with the Ferus crowd, and saw his own work and that of his friends and peers on the walls of Brooke and Dennis’s house. The whole scene caused Warhol, as Dennis recalled, to stand agog and emit the ultimate Warholian words of approval: “Ooh! Aah!”

“He loved it,” Brooke said. “He was simply dazzled.”

“Andy comes to Hollywood and sees an environment that actually accepts this kind of new art,” Dennis remembered. “It was a very thrilling thing for everybody at that point. Because it was the first time anybody saw a collection like this together with antiques and with the kind of outrageous stuff that we had found.” To Warhol, 1712 was a fun park: “This was before things got bright and colorful everywhere, and it was the first whole house most of us had ever been to that had this kiddie-party atmosphere.” Ed Ruscha, who’d had his first Ferus show a few months earlier, said, “It was like walking into a carnival, with a candy-store energy.” As for the party itself, “That was noisy!” It was also sweltering hot.

Dennis Hopper/Hopper Art Trust: Andy Warhol, Henry Geldzahler, David Hockney, and Jeff Goodman in Dennis’s lens, New York, June 1963.

Dennis Hopper/Hopper Art Trust: Andy Warhol, Henry Geldzahler, David Hockney, and Jeff Goodman in Dennis’s lens, New York, June 1963.

Mead found the Hollywood crowd a little stiff, but that changed soon enough as cocktails and other substances flowed. “Joints were going around,” Warhol recalled, “and everyone was dancing to the songs we’d been hearing on the car radio.” Chamberlain claimed that Brooke got huffy when she discovered him smoking pot in a closet with Ben Hecht’s daughter Jenny. Malanga said that was unlikely, and, given Dennis’s long-standing devotion to cannabis, it would have been more shocking had the party not been fueled by it.

As records spun on the Garrard KLH turntable in the living room, Mead found a willing dance partner: Patty Oldenburg (later known as Patty Mucha), the firecracker wife of Claes. Dennis and Brooke had met the Oldenburgs in New York when Geldzahler had taken them to a party at the couple’s Lower East Side apartment, and now they were reciprocating the hospitality. The Oldenburgs had since moved to LA, finding a little house on Linnie Canal in Venice.

Taylor and Patty were fierce dancers—“I could dance five hours straight in high heels in those days,” she said—and as they were twisting and mashed potatoing, Patty knocked into a creepy Kienholz assemblage called The Quickie, a female mannequin head and hand planted on top of a roller skate and affixed with gold braid that Brooke and Dennis had bought for $350. It was a favorite piece of Brooke’s, and it crashed to the floor, the head shattering. “It was a high point of the party,” Brooke said. She waved the incident away, and the guests got back to partying. But Patty was mortified. “I thought it was a monument to her beauty,” she said of The Quickie, “because the mannequin head was so beautiful and Brooke was so beautiful and classy and fashionable and down to earth.” (Kienholz repaired the piece.)

As the Hollywood Hills turned dark, Warhol, Malanga, Chamberlain, and Mead got into the Falcon and rolled back down to Sunset, heading over to the Beverly Hills Hotel, where Brooke had arranged for them to stay in Leland’s preferred suite. “The Hoppers were wonderful to us,” Warhol remembered. “This party was the most exciting thing that had ever happened to me.” As a thank-you, he sent over an enormous heart-shaped flower arrangement on a stand, the kind of thing you might see at a funeral home out in the Valley. The card read, “Darling Brooke, Love, Andypoo.”

“When I met Andy Warhol, who came to this party, who came to this house, to this weird scene with the strange bathroom that had been transformed,” Brooke said, “the world began.”

__________________________________________________________

From EVERYBODY THOUGHT WE WERE CRAZY by Mark Rozzo. Copyright © 2022 by Mark Rozzo. Excerpted by permission of Ecco, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers.

Mark Rozzo

Mark Rozzo is a contributing editor at Vanity Fair. He has also written for the Los Angeles Times, the New Yorker, the New York Times, Esquire, Vogue, the Wall Street Journal, the Oxford American, the Washington Post, and many others. He teaches nonfiction writing at Columbia University.