Behind the Fame (and Inspirations) of Muriel Spark

Frances Wilson on the Similarities Between Spark’s Favorite Teacher and Her Most Famous Protagonist

“Perhaps no other life could have been as rich as that first life,” Spark recalled in Curriculum Vitae, “when, five years old, prepared and briefed to my full capacity, I was ready for school.” James Gillespie’s, famous in Edinburgh even before it became the Marcia Blaine School for Girls in The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie, was a Presbyterian fee-paying establishment with a Protestant, Jewish and Catholic intake. It was a ten-minute walk across the park from Bruntsfield Place, and Muriel was awarded a bursary between the ages of five and twelve after which, as one of the school’s stars, she was educated for free. Her schooldays were the happiest of her life, and thirty pages of Curriculum Vitae—one sixth of the book—are reserved for recollections of her teachers.

Spark thrived in institutions. This is because, like Miss Brodie, she was a conservative anarchist. Her anarchism was part of the Edinburgh Character and her conservatism rooted in respect for order, authority and ritual. Her first best friend was a girl called Daphne, who died suddenly, for reasons unknown; her new friend Frances Niven also liked reading and writing. The Nivens lived in Howard Place, next door to the house—now a museum—where Robert Louis Stevenson had been born, and Muriel and Frances would slip through a gap in the hedge to play in his former garden. This was her first experience of breaking into a writer’s house, to draw the power from his presence.

When the novelist Shirley Hazzard asked why Sandy Stranger, Spark’s alter ego in The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie, was famous for her piggy eyes while Spark’s own eyes were so huge, Muriel replied that she used to have small eyes but they enlarged with knowledge.

In the 1929 class photograph Muriel looks larger in scale than the other girls, which is curious considering how small she would be as an adult. Plump as a child, she battled with her weight all her life, the shape of her face altering according to whether she was going up or down on the scales. At her heaviest she looked moonlike; at her lightest (in her forties and fifties) she looked angular, with a square-set jaw. Even her eyes and nose seemed to grow and shrink.

When the novelist Shirley Hazzard asked why Sandy Stranger, Spark’s alter ego in The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie, was famous for her piggy eyes while Spark’s own eyes were so huge, Muriel replied that she used to have small eyes but they enlarged with knowledge. She played a similar trick with size in her novels, which seem larger than they are and survey their subject as if from the wrong end of a telescope.

Her education was a synthesis of Classical and Romantic, with the Scottish grounding in logic, reason and intellectual persuasion given a fillip by the improvisations of Miss Christina Kay. Miss Kay, who taught Muriel between the ages of eleven and thirteen, both was and was not the model for Miss Jean Brodie. Their mannerisms and speech patterns were the same, and they selected certain girls as her favorites—the “Kay set” consisted only of Muriel and Frances Niven—but Miss Kay was eccentric and kind while Miss Brodie a creator of fictions obsessed by betrayal. By 1961, when The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie was published, Jean Brodie was closer to being a portrait of Muriel herself.

Artists, Miss Kay instructed her class, were in the “destined category,” and she, like Muriel, was an artist. Miss Kay’s philosophy was beauty and truth, both of which she found everywhere, including in etymology, mathematics and grammar; reproductions of paintings by Leonardo, Botticelli and Giotto were taped to the walls. (“Who is the greatest Italian painter?” Miss Brodie asked her girls. “Leonardo da Vinci, Miss Brodie.” “That is incorrect. The answer is Giotto, he is my favorite.”)

Miss Kay was a performer whose stage was the classroom; when she described her summer holidays in Italy, Egypt and Switzerland, it was as if Muriel had been there too. Muriel wrote poems inspired by Miss Kay’s adventures and Miss Kay’s lessons on relativity, she read whatever Miss Kay recommended, including the Bible and books on astronomy; she imagined Miss Kay before the war, waltzing in her long skirts, and Miss Kay losing her sweetheart in the trenches. Muriel “sensed” in Miss Kay “romance, sex.”

It was Miss Kay who explained poetic metre, demonstrating the difference between trochees and spondees, villanelles and triolets. Muriel, who liked the rules of poetry because she liked rules in general, would always call herself a poet and her novels poems. Aged nine she rewrote Robert Browning’s “Pied Piper of Hamelin,” giving it an ending where the children, rather than disappearing into the mountains, return to their families, and under Miss Kay’s tutelage she read Wordsworth, Tennyson, Swinburne, Yeats, Robert Bridges and Alice Meynell. Aged eleven she had her first poem, “Snowflakes,” published in the Gillespie’s High School Magazine. The following year the magazine’s editors broke their policy of printing only one contribution from each author because “the work of Muriel Camberg, aged 12, is so much out of the ordinary that we feel it worthwhile to give the following five of her poems.”

It is striking how certain Muriel was in her footing. There is as little self or sentiment in her juvenilia as in her adult writing; her focus from the start was on sound and form, and her inspirations came not from her own sensibility but from other poems.

At the same time, the Edinburgh publishers Oliver and Boyd brought out an anthology called The Door of Youth—A Selection of Poems from Edinburgh School Magazines, with a discouraging preface by John Buchan. Youthful experiments in verse, Buchan intoned, however “limpingly expressed,” were useful mainly as an aid to writing good prose: “nobody will be perfectly at home on horseback who only jogs along the highroad; to get a perfect seat you must ride across country.” The dedicatory poem, “To Everybody,” was by Muriel Camberg, which meant that The Door of Youth was effectively her own: “I put zeal and zest / In the things I love best, / ’Tis a verse which I give up to you.”

Four further poems by Muriel were included in the volume, each faultlessly controlled: “The Sea” was a study in sound, imagery and rhythm (“Now galloping! now trotting! now walking at a pace!”), “The Victims” was a Blakeian reflection on innocence, “The Winding of the Horn” was inspired by Masefield’s Reynold the Fox, and “Time” was a witty and self-referential play on her favorite theme: “But as I write this verse on ‘Time,’ / That self-same time is flying.”

It is striking how certain Muriel was in her footing. There is as little self or sentiment in her juvenilia as in her adult writing; her focus from the start was on sound and form, and her inspirations came not from her own sensibility but from other poems. Her continued elevation in her parents’ esteem will have been felt keenly by seventeen-year-old Philip, working for the past three years in the same factory as his father.

The success of his sister was unstoppable: in 1932 she was crowned Queen of Poetry when a racy ballad “Out of a Book” won first prize in a competition to commemorate the centenary of the death of Sir Walter Scott. A photograph in the local press showed her perched on a makeshift throne with a coronet (“Tinsel,” her headmaster muttered) being lowered on to her head by an American movie star called Esther Ralston.

It was at school that Muriel first became famous; when she became famous again, after The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie had been published, she was picking up the thread of her early years.

It was demeaning, Muriel felt, for a poet to be treated like “the Dairy Queen of Dumfries” and, noting the insult to her pupil’s dignity, Miss Kay pointed out to her class how the camera had caught “the sensitivity in that line of Muriel’s arm.” Muriel’s prize was The Oxford Book of Ballads and Scott’s Minstrelsy of the Scottish Border, whose “lyricism, savagery, love and revenge” entered her “cognition” and “emotional system.” Tough, cruel, supernatural tales, the Border ballads contained “a mysterious and irrational blend”of characters: those who used “their power to the utmost drop of blood” and those who refrained “from using their power at all except for good.” The characters she met in ballads were, Muriel felt, “microscopic examples” of the people she would meet as an adult, and she was right.

As a schoolgirl, Muriel was revered by staff and pupils alike. She may not have been, like Dr. Johnson, carried into school on the shoulders of her classmates, but she was praised in assemblies, pointed out in corridors, deferred to by her English teachers (Alison Foster, who replaced Christina Kay in the senior school, stayed in touch with Muriel for the next twenty years). It was at school that Muriel first became famous; when she became famous again, after The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie had been published, she was picking up the thread of her early years.

Being poetic did not make her impractical. Because Miss Kay prized organization and efficiency, Muriel knew how to run an office; because Miss Kay taught assertion in the face of bureaucracy, Muriel knew how to challenge an invoice. In one of her finest performances, Miss Kay gave a triumphant account of querying a bill at the Edinburgh gas office: “That taught them to sneer at a businesslike young woman.”

If Spark’s own letters to the Inland Revenue show clarity of purpose it is because she learned from the best. She also learned from Miss Kay that in Paris a grey suit should be worn with a “a citron beret,” that in rain “We should wear bright coats, and carry blue umbrellas or green,” and that Corot could be recognized “by his small touch of red, such as a hat.” Miss Kay introduced Muriel to the Brontës, who became an obsession, and to Mrs Gaskell’s Life of Charlotte Brontë, her first experience of biographical manipulation. She also took Muriel and Frances to the Empire to see Anna Pavlova dance The Dying Swan, which was the ballerina’s last tour.

When the swan died, Muriel remembered, her nails tapped twice on the stage. On October 18, 1930, Miss Kay took them to Moray House, the Church of Scotland Training College where she had trained to become a teacher, to hear John Masefield, the poet laureate, read from Dauber. Muriel had expected the sailor poet to sport an anchor tattoo and to swear round oaths, but he was civilized and self-possessed, reading his work as if it had been written by someone else, “and that is a very difficult thing for a poet to do.”

She remembered the quality of his voice for the rest of her life, drawing from it her understanding of how to “preserve” oneself as an artist. Miss Kay took them to the cinema, and to Holyrood Palace where they saw Mary Stuart’s apartments; Muriel and Frances were to say nothing about these treats to the rest of the class, Miss Kay insisted, “lest they should feel it is favoritism.”

__________________________________

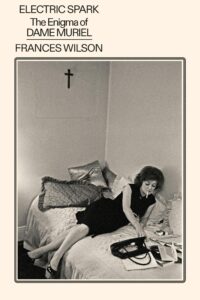

From Electric Spark: The Enigma of Dame Muriel by Frances Wilson. Used with the permission of the publisher, Farrar, Straus and Giroux. Copyright © 2025 by Frances Wilson.

Frances Wilson

Frances Wilson is a critic, a journalist, and the author of six works of nonfiction, including How to Survive the Titanic: or, The Sinking of J. Bruce Ismay, which won the Elizabeth Longford Prize for Historical Biography; Guilty Thing: A Life of Thomas De Quincey, which was a finalist for the National Book Critics Circle Award and the Los Angeles Times Book Prize and was long-listed for the Baillie Gifford Prize; and Burning Man: The Trials of D. H. Lawrence, which won the Plutarch Award, was short-listed for the Duff Cooper Prize and the James Tait Black Award, and was long-listed for the Baillie Gifford Prize.