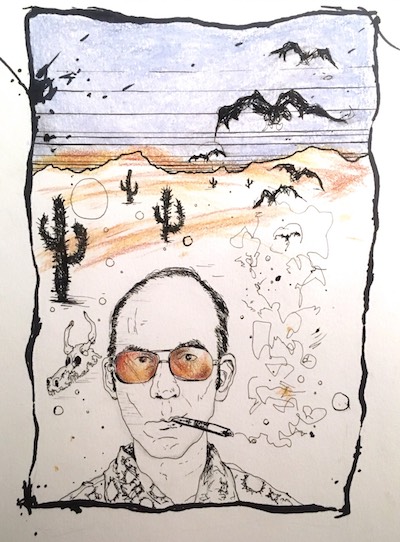

Behind the Dedications: Hunter S. Thompson

A look at the family, friends and substances to which Thompson dedicated his books

On February 16, 2005, Hunter S. Thompson was sitting in his home in Woody Creek, Colorado. Football season had just ended, which always left him morose, but he was also suffering from surgery-related pain in his hip and back, which made walking difficult—to say nothing of his favorite activities, swimming and blowing things up. Instead, the then 67-year-old author composed a typewritten note addressed to himself:

No More Games. No More Bombs. No More Walking. No More Fun. No More Swimming. 67. That is 17 years past 50. 17 more than I needed or wanted. Boring. I am always bitchy. No Fun—for anybody. 67. You are getting Greedy. Act your old age. Relax—This won’t hurt.

Four days later, Thompson shot himself. He was sitting at the kitchen table, where he did much of his writing.

Before his death, Thompson had published 15 books—some journalism, some fiction, many his own brand of the two, which a friend dubbed “gonzo journalism.” Throughout those works, Thompson pays tribute to his family, friends and influences, often through dedications, although sometimes in exceedingly vague terms. His masterpiece Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas, for example, is in part dedicated to Bob Geiger “for reasons that need not be explained here.” Those reasons are explained below.

“To Sandy, who endured almost a year of grim exile in Washington, DC while this book was being written.”

–Fear and Loathing on the Campaign Trail ‘72

Sandy Thompson (nee Conklin; now Sondi Wright) was Hunter’s first wife. The two met through mutual friends in New York City in 1958. Reflecting on first falling for Hunter in Gonzo: The Life of Hunter S. Thompson, an oral biography by Jann S. Wenner and Corey Seymour, Sandy declares, “The only way to say it is that I was just gone. Absolutely gone.” In a letter from The Proud Highway: Saga of a Desperate Southern Gentleman, a collection of Hunter’s correspondence, he pleads with her to visit him in Puerto Rico, where he had moved in 1960. Hunter writes:

I am still honest enough to say I want you to come down and, if you do nothing else, merely lie naked with me on this living room bed and stare at the sea… I am also honest enough to admit that wanting you over this past weekend rubbed raw some part of me that’s been well-insulated for quite a while.

Sandy did eventually visit, and three years later, the couple wed.

In order for Hunter to cover the presidential campaign in 1972, the family, which now included their eight-year-old son Juan, moved from their home in Woody Creek to DC. These articles for Rolling Stone would eventually be compiled into the lauded Fear and Loathing on the Campaign Trail ‘72 (“The best account yet published of what it feels like to be out there in the middle of the American political process,” according to The New York Times Book Review), but the experience also put inhuman strain on Sandy. As Wenner, Hunter’s editor at Rolling Stone, says in Gonzo:

Sandy was not only his wife but also his full-time assistant. She was the one typing the manuscripts, filing, and doing all the administrative work, and she was also the recipient of Hunter’s abusive behavior and unrelenting late-night irritability.

Unsurprisingly, the union did not last. Sandy left Hunter in 1980, after 17 years of marriage. She saw him through the publication of his first four books—a selection which undoubtedly contains his finest work, and in which she undoubtedly played an indelible role.

“To Juan and… To Richard Milhous Nixon, who never let me down.”

–The Great Shark Hunt

Thompson’s only child, Juan Fitzgerald Thompson, was born in 1964. A month after Juan’s birth, Thompson—beaming in his own way—wrote to a friend:

My son is here with me; he can’t sleep at night except by the typewriter. … He groans and thrashes about constantly, as if in close combat with the dark forces of reaction. He has a dangerous amount of energy and a huge set of balls, a sure formula for trouble.

Nixon, on the other hand, was Thompson’s one true nemesis. By 1963, Thompson was already writing to one of his editors, “With a hairy animal called Nixon looming once again on the horizon, I am ready to believe that we are indeed in ‘the time of the end.’” After the two men met in 1968 on the campaign trail, Thompson described Nixon as “a monument to all the rancid genes and broken chromosomes that corrupt the possibilities of the American Dream.” That hatred only grew through the president’s first term and with the prospect of his second. On the eve of the presidential election in 1972, Thompson railed in Rolling Stone, “Nixon represents the dark, venal and incurably violent side of the American character that almost every other country in the world has learned to fear and despise.” Even upon Nixon’s death in 1994, Thompson seethed in his obituary, “He could shake your hand and stab you in the back at the same time.”

In their own ways, then, both Juan and Nixon inspired the essays and articles that Thompson wrote throughout the late 1960s and early 70s, the best of which are collected in The Great Shark Hunt.

By Gabriella Shery

By Gabriella Shery

“To Bob Geiger, for reasons that need not be explained here—and to Bob Dylan, for Mister Tambourine Man”

–Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas

The most mysterious of Thompson’s dedications is to Bob Geiger, an orthopedic surgeon from Sonoma, California. Geiger’s wife had met Sandy at a town square, where they struck up a conversation about children (they both had one-year-olds) and writing (Geiger was a novelist). The Geigers invited the Thompsons over for dinner and a friendship blossomed.

In Gonzo, Geiger himself guesses at his dedication:

People think that Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas is dedicated to me because they think I was supplying Hunter with drugs, but the main reason is that I would drive down to San Francisco almost every night, and Hunter and I would read through the Hell’s Angels manuscript page by page, word by word.

No doubt a contributing factor, but not an explanation as to why Fear and Loathing—as opposed to Hell’s Angels—is dedicated to Geiger. The whole truth likely includes an instance in the mid 60s, when the Thompsons were evicted from their apartment (after Hunter and Bob were shooting at gophers) and the Geigers housed them for some time. But even more relevant to the gonzo nature of Fear and Loathing may be this quote from Geiger:

I had published a novel, and Hunter had this horse’s-ass idea that it was supposed to be important to be a fiction writer. I would try to point out to him, “Hunter, you are writing fiction. All writing is fiction. Experiences you experience, and words are words, so everything is fiction.”

As for Bob Dylan, he was Thompson’s favorite musician. Of the author’s musical taste, his literary executor Doug Brinkley says, “He knew what he liked … it was Dylan first and foremost.” In a letter to a friend, Thompson himself writes, “Dylan is a goddamn phenomenon, pure gold, and mean as a snake.”

Dylan’s song “Mister Tambourine Man” was particularly close to Thompson’s heart—and to Fear and Loathing. In a memo to his editor at Rolling Stone, which published an early version of the novel, Thompson even compares his book to Dylan’s song, writing, “The central problem here is that you’re working overtime to treat this thing as Straight or at least Responsible journalism … You’d be better off trying to make objective, chronological sense of … ‘Mister Tambourine Man.’”

Thompson’s memo hints at a more significant, if personal connection between his book and Dylan’s song. Years earlier, Thompson documented at length what “Mister Tambourine Man” meant to him:

This, to me, is the Hippy National Anthem. … To anyone who was part of that (post-beat) scene before the word “hippy” became a national publicity landmark (in 1966 and 1967), “Mr. Tambourine Man” is both an epitaph and a swan-song for the lifestyle and the instincts that led, eventually, to the hugely-advertised “hippy phenomenon.”

Those reflections were published in another collection of his letters, Fear and Loathing in America: The Brutal Odyssey of an Outlaw Journalist, and reveal a sentiment that rings so close to Thompson’s own ideas about the hippie era, as captured in Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas:

San Francisco in the middle 60s was a very special time and place to be a part of. … We had all the momentum; we were riding the crest of a high and beautiful wave… So now, less than five years later, you can go up on a steep hill in Las Vegas and look West, and with the right kind of eyes you can almost see the high-water mark—that place where the wave finally broke and rolled back.

At his request, “Mister Tambourine Man” was also played at Thompson’s funeral, after his ashes were shot from fireworks, in true gonzo style.

For more on Hunter S. Thompson and those he loved, see Gonzo: The Life of Hunter S. Thompson, The Proud Highway: Saga of a Desperate Southern Gentleman and Fear and Loathing in America: The Brutal Odyssey of an Outlaw Journalist.

Featured illustration: Gabriella Shery