A Friday in August, 2001. A bedroom on Fairmount Road, Brixton. Against the orange wall neat piles of jeans, along row of trainers. The room is Malika Booker’s, but she’s not here yet. On the floor near the futon two women are crouched next to one another. Patricia Foster and Janett Plummer. Others have found elsewhere to sit. By the wall a shy American leans, watching. Peter Kahn.

Then, suddenly, a towering figure bounds in, wearing his trademark hat.

Alright. Let’s get started. Roger Robinson.

It’s the second session of a collective that have no idea that they are about to begin something that will have a groundbreaking influence on the poetry scene in the UK, affect hundreds of poets in this country and beyond, and help place a new generation of voices into the landscape.

*

In 2001 the popularity of a certain type of poetry is on a high. Every night of the week words are being woven, in cafés and bars, galleries and pubs. The spirit is of experimentation; there is a sense of possibility.

But this “performance poetry” or “spoken word” is happening underground. Where it rises to the surface, it comes up against a brutal, seemingly impenetrable barrier. These labels aren’t just used to classify, but to keep in place. From down below: the experienced, but unrecorded, experimental, electrifying scene.

And then up there, bright and elevated, talked and written about: the part of the poetry world that self-consciously calls itself “page poetry,” meant to last, meant to be more prestigious.

A week earlier, Patricia and Janett are on their way to a poetry workshop in Hammersmith. There is no particular reason for them to go through Charing Cross that night, but Janett suggests they do. Walking through the station, they see a tall man approaching. They recognize the hat.

You gotta come. You gotta come! Roger is buzzing with the infectious, insistent energy people know him for. They just had their first meeting (only three people were there). Why don’t you come next week? We’ll do it again. Come next Friday! Patricia hasn’t been sure about her poetry for some time. She feels confused about where it’s going next, what she wants it to do. On the train afterwards, she has a strange, overwhelming feeling. I have to do this.

He has always liked poetry on the page; now he’s discovering what it can do on a stage, the spaces it can open up, for him as a poet, for those around him.

Page poetry—in magazines, newspapers, journals, books—is, in 2001, overwhelmingly white. The shortlists of the Forward Prizes for Poetry: white. The shortlist of the T. S. Eliot Prize. Every editor of every journal of note: white. Almost every one of their pages. When the first group of Next Generation Poets is drawn up in 2004, there is no Black or Asian poet on it. A frantic call goes out for ethnic names to be submitted.

On the morning of the collective’s second meeting, Peter is standing outside the Centerprise bookshop on Kingsland High Street in Dalston. The young educator has only just arrived in London from Chicago. He knows very little about poetry. In fact, up until recently, he has actively hated it. Hated reading it, hated teaching it. But when a student takes him to a poetry slam, a lightbulb goes on. Now he’s in London to learn as much as he can about using poetry in teaching. But he doesn’t know anybody. Asking around, someone tells him: You should speak to Malika Booker.

Peter pushes the door open and enters the community bookshop where Malika is currently working. She is standing behind the counter. They start talking. Peter tells her he works in a school.

Malika is interested.

So, are you a poet?

Well, I write with my students . . . Okay, so you are a poet.

She tears out a small piece of paper and writes on it. She hands it over. It’s an address in Brixton.

When Peter knocks on Malika’s door at 7 p.m. that night, punctual as always, someone other than Malika opens the door. He is invited in: The bedroom is upstairs. As he heads up, Malika rushes down, ready to go out. Oh hi, Peter. A poet she has admired for years, Ruth Forman, is in town. I need to see her, but you stay here. Can you let people in? Left alone, Peter sits himself down in the bedroom of someone he has only just met. But it’s not long before others ring the doorbell.

*

Malika Booker is born in London, to Guyanese and Grenadian parents. She moves away to spend eleven years of her childhood with her mother, father and two brothers in Guyana. Two important things happen to her: she discovers a love of storytelling, and she lives through a deeply conflicted relationship with her grandmother which, years later, will inform much of her poetry.

She begins writing and performing aged nineteen. A decade later, the theatre follows: one-woman shows, a musical. Her debut stage show, Absolution, gets commissioned by the Austrian Cultural Institute and Apples & Snakes; it premieres at the Battersea Arts Centre in 1999. Her first published poem appears in Bittersweet: Contemporary Black Women’s Poetry the same year.

Halfway through her early career, Malika is studying anthropology at Goldsmiths, University of London. She likes it, but the final year is torturous: all around her, poet friends are performing in London, across the country, abroad. Malika is a little jealous. She wants to be with this crowd. By the time her final exam comes, she’s clear with herself. It’s poetry now, or nothing. Everything she does, from this moment on, is to facilitate her career as a poet. She refuses to claim unemployment benefit, or work in any other field, until it happens. Her flatmates are supportive, let her pay less rent. They understand. Everyone knows how serious she is about this.

Malika meets Roger’s sister before she meets Roger. The three become friends. Suddenly, Roger is everywhere. At the soul and calypso concerts Malika loves. At hip hop events. Seeing the Roots, the Fugees. She attends some live arts event at the ICA, and who is there? Roger Robinson. At almost any literary event she goes to. Always scribbling into his small notebook.

Roger is acutely aware that if you are Black, no matter how good you are as a poet, people don’t see you. If, every now and again, a door opens to let some people through, it soon shuts again. And if you find yourself on the margins, anywhere outside of it, the poetry world can look and feel not just out of reach, but completely impenetrable.

Roger feels—painfully, every day—how every structure is against him, and poets like him. Many give up. But Roger pushes on, keeps saying to others: We are all going to write! We are all going to continue! This crazy shit won’t grind us down.

Like Malika, Roger is born in London (in Hackney), moves away as a child (aged four, to Trinidad), and returns to the UK (when he’s nineteen). In Trinidad, he listens to his mother, a great storyteller, at the dinner table, and grows a love for words, for language.

In the UK, he ends up in Ilford, Essex, and initially lives with his grandmother. It’s a culture shock. Eventually, he will pack his bags and settle in Brixton, the neighborhood he will relentlessly observe, negotiate and turn into art for decades to come. There’s a lot of back and forth, a life between the UK and Trinidad, before, years down the line, Roger decides: I’m here. I’m Black British.

In London he starts performing with dub bands, becomes the lead vocalist for the crossover project King Midas Sound, records solo albums. The man is music; but the man is poetry first.

By now, Malika has found a job. Apples & Snakes—founded in the early 80s by a group of poets in a room above a pub and speedily growing into the country’s leading spoken-word poetry organization—have hired her as their education coordinator. Shortly after she joins, they bring in Roger as their programmer: the two friends are now also colleagues.

In a derelict building in Deptford, Malika is brainstorming ideas for new shows, plotting, initiating. She watches, listens, absorbs. She makes connections. Her kitchen becomes a casual meeting point for the many US poets Roger is bringing over at this time: Saul Williams, Will Power, Sarah Jones.

One British poet who find himself there is Jacob Sam-La Rose. The young Londoner is roaming the spoken-word scene, at gigs night after night, seeing whatever he can: spoken word, MCs, hip hop artists, actors. He has always liked poetry on the page; now he’s discovering what it can do on a stage, the spaces it can open up, for him as a poet, for those around him. The vibe is can-do optimistic, up for it.

On the circuit, he starts noticing the same tall poet with a hat, again and again. They start talking. Not much later, Malika is in his view too. And the two of them begin to notice Jacob: his energy, his drive. When Jacob starts coming to Malika’s house, a bond forms. Are you up for running workshops?

The numbers grow—quickly. Word spreads. It’s like a secret knock. You write poetry? Come down!

Around the corner from Malika, in Brixton, a new literature organization has been setting up, offering courses in writing development. Spread the Word. Malika gets hold of their first brochure. She signs up for pretty much every course they offer. Poetry. Fiction. Short stories.

One of them is led by Kwame Dawes. The Ghanaian poet, actor, editor, critic and musician, who has spent most of his childhood in Jamaica, will become one of the biggest influences on her writing, and on her life. Later, people will look back at his workshop, which is running under the banner “Afro-Style School,” and say that it was a first meeting point. A chance.

When Kwame Dawes leaves, Malika and Roger feel a terrible void. What we need is a space where people can come together. Write together, and build. It’s not much later that, over a shared meal, Roger will say: What are we waiting for? Let’s just do it. After the second night, Patricia, Janett, Peter and the others are leaving, elated. Everyone is saying: See you next Friday?

Malika and Roger look at each other. They hadn’t really thought beyond this point. But they say: Okay.

*

The numbers grow—quickly. Word spreads. It’s like a secret knock. You write poetry? Come down!

People are hearing it all over town. Like the young law student Sundra Lawrence, who has just moved into publishing, looking for something more creative to do with her life. Back then there is no online community she can easily tap into, no way to follow or sign up. All she can think of is to try and get to a poet she has seen to be very active locally: Anjan Saha. They meet; he tells her about Kitchen. It clicks immediately. She marvels at the professionalism of something she thought people treated like a hobby. She thinks: Gosh, I need to up my game. Or the editor and journalist Denise Saul, who’s just decided to make writing fiction the focus of her life. Her local library recommends a workshop led by Jacob Sam-La Rose. She misses it, but the librarian gives her Jacob’s email address. Denise sends him some of her work. Come to Kitchen, he says.

At the first session she attends he suggests that, really, her short story should be a poem. Denise has no interest in writing poetry. But she considers this. Over the next year and a half, she will become one of the collective’s most active members. Writing, performing, living poetry.

The Kitchen quickly finds its own rhythm: they read poetry, they write poetry, they critique each other’s work. Roger will go: Let’s see.

Patricia has gathered all her courage to bring in this poem she has written about visiting her grandfather in Jamaica. Roger takes out his pen, and begins: Right, don’t need that. Patricia shivers.

Don’t need that. Don’t need that. Don’t need that.

Patricia looks at him. Oh my god. That’s half the poem gone!

But she makes the changes anyway. Like everyone in the collective, she trusts the process, whoever is critiquing the poem. Because it’s only ever the poem, never the person. And there is only one aim: to make the poem as good as it can be. This dedication is Kitchen’s heartbeat. They realize that there is always room to improve your craft, no matter who you are. Patricia will go back to her piece with a new confidence. “Granddad” will move with her, performed in the UK and abroad, one of her dearest pieces.

It doesn’t take long for Kitchen to have something to work towards: the group has been invited to perform, as a collective, at the Bug Bar in Brixton. Malika asks them to choose three pieces each, refine and practice them. Know them inside out. Everyone is determined to have stage presence for the night. Everyone wants the work to be as tight as it can be.

At the margins of the establishment, a bunch of poets are carving out a space. To many of them, it feels like they’re being given a new kind of permission: to write about things that come from a really painful place. To speak for themselves. Of themselves. And they know: Literature is not entertainment; it’s a form of social change. This belief charges the room, like electricity. The response to the injustice ingrained in the system that produces the country’s literary culture is a bedroom in Brixton. Every Friday.

September 12, 2001. The Bug Bar, Brixton. The night is sold out: two hundred people fill the room. Patricia kicks things off. It’s her first time on a stage since leaving school. Stepping up to the microphone she can feel her nervousness, but it fades with the reassurance of her fellow Kitchen members in the audience. She begins.

One after the other, the poets step up to the microphone, not just reading, but performing. Many are doing this for the first time in their lives, reaching deep into themselves; sharing with generosity, and with a new and still unfamiliar confidence. There is an undeniable, inescapable energy about the collective that night. It floats from the stage, touching those listening.

One of them is an American woman called Maya. She comes over straight after. Guys. I want to book you, as a collective, for one of our shows. It’s at the Battersea Arts Centre. Hot on the heels of its first-ever outing, Kitchen has its second gig in the bag.

Afterwards they stand together, a little delirious from what happens when you perform poetry to an audience and the audience catches on. What’s next?

Read poems from Jacob Sam-La Rose, Ugochi Nwaogwugwu, and Peter Kahn.

__________________________________

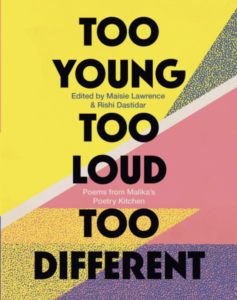

From Too Young, Too Loud, Too Different: Poems from Malika’s Kitchen edited by Maisie Lawrence and Rishi Dastaidarm published by Corsair, an imprint of Little, Brown Book Group Ltd. Copyright © 2021, Malika’s Poetry Kitchen.

Daniel Kramb

Daniel Kramb is a writer and poet. He is the author of three novels: the story of a London rebellion, Central (2015); From Here (2012), about climate change; and the Hackney-set Dark Times (2010); and a booklet of poetry: Timid Takes (2013). Look at Us is a stage collaboration with the writer and poet JJ Bola. Daniel runs the Lonely Coot small press, and is collaborating with Jean Casey on Sin Scéal Eile, a listening project that turns life stories into poetry. Originally from Germany, Daniel lived in London for sixteen years, and is now based in Westcliff-on-Sea.