Things here are going from bad to worse. Last week my aunt Jacinta passed away, and then on Saturday, after we got her buried and the sadness was beginning to settle, it started to rain like never before. That made my father good and mad since the entire barley harvest was laid out in the sun to dry. And the storm came on quick, dropping huge waves of water, not giving us any time to put away even a handful. All we could do, everyone in my house, that is, was huddle together under the shed and watch as freezing water fell from the sky, scorching that freshly cut yellow barley.

And then yesterday, with my sister Tacha having just turned twelve years old, we learned the river had swept away the cow my father gave her as a gift for the day of her saint.

The river began rising three nights ago, sometime in the early morning. I was fast asleep, but the racket as the river swept along woke me right up, making me jump out of bed with my blanket still in my hands, as if I had imagined the roof of the house was crashing down. But I drifted off again when I recognized the sound of the river and when that sound began to even out until it lulled me back to sleep.

When I got up, the morning was full of heavy clouds, and it felt like the rain hadn’t let up at all. You could tell the noise from the river was stronger and sounded closer. And it reeked, like the smell of something burning, like sour water that’s been stirred up.

By the time I went to have a look, the river had spilled over its banks. Bit by bit, the water was making its way up the main road, and it quickly began pouring into the house of that woman they call La Tambora. You could hear the water splashing around as it entered through the back corral and exited in huge gushes through the front door. La Tambora was plodding back and forth through what was now part of the river, tossing her hens into the street so they could find a place to hide where the current wouldn’t get to them.

On the other side, over by the bend, the river must’ve washed away the tamarind tree from my aunt Jacinta’s yard, who knows when, since now there’s no tamarind tree to be seen. It was the only one in town, and that’s how come people figure the surge we’re seeing is the biggest to come down the river in years.

My sister and I headed back out in the afternoon to observe the mass of water that just keeps getting thicker and darker and that’s now passing way above where the bridge ought to be. We sat there watching it all for hours and hours without getting tired. After that, we climbed up the barranca hoping to hear what people were saying, since down below, next to the river, the rumbling is so strong you just see a bunch of mouths that open and close as if trying to say some-thing, but you don’t hear a thing. That’s why we climbed to the top of this ravine where others are watching the river and talking about all the damage it’s done. That’s where we learned the river had taken La Serpentina, my sister Tacha’s cow, the one my father gave her for her birthday and that had one white ear, another one red, and very pretty eyes.

I just can’t figure out why La Serpentina would’ve got it in her head to cross the river, when she knew it wasn’t the same one she was used to most days. La Serpentina was never that dim. She must’ve been snoozing to let herself be killed like that for no reason at all. There were many times I had to wake her after opening the corral, or else she’d have spent the whole day in there with her eyes shut, good and relaxed and sighing, just like you hear cows sigh when they sleep.

That’s got to be what happened, that she fell asleep. Maybe it occurred to her to wake up when she felt the heavy water hitting against her ribs. Maybe she got scared and tried to come home, but as she turned around, she found herself confused and bogged down in that black water that was as thick as quicksand. Maybe she bellowed calling for help.

Bellowed as only God knows how.

I asked a man who watched as the river dragged her away if he hadn’t also seen the young bull that was with her. But he said he wasn’t sure if he’d seen him. All he could say was that a spotted cow floated past, hooves in the air, close to where he was, and that’s where she flipped over, and then he saw no more horns or hooves or any other sign of any cow. Scores of tree trunks were rolling down the river, roots and all, and the man was so busy gathering firewood he didn’t pay attention to whether they were tree trunks or animals being dragged along.

That’s why we don’t know if the calf is still alive, or if he followed his mother downriver. If that’s what happened, may God help them both.

What’s got everyone at home worked up is what’s gonna happen tomorrow now that my sister Tacha’s been left with nothing. Because my father worked hard to get La Serpentina when she was just a calf and give her to my sister, so she’d have her own little bit of capital and not become a whore like my other two sisters, the older ones, did.

According to my father, they went bad because we were so poor in my house, and they were so unruly. Even when they were little, they were pigheaded. And as soon as they got older, they began running around with the worst kind of men, ones who taught them bad things. They learned real quick and soon recognized the whistling that would call for them late at night. Later, they’d even go off during the day. They were always heading down to the river to fetch water, and sometimes, when you least expected it, they’d be over in the corral rolling around on the ground, buck naked, each one with some guy perched on top of her.

That’s when my father ran them off. At first, he tried put-ting up with them, but in time he couldn’t take it anymore, and he threw them out on the street. They left for Ayutla, or somewhere else, I don’t know, but they’re whoring around.

That’s why my father’s so worried now for Tacha, not wanting what happened to my other two sisters to happen to her if she gets it in her head how poor she is after losing her cow, how there’s not gonna be nothing to keep her busy while she grows up and can marry a decent man, one who’ll love her forever. All that’s gonna be hard now. With the cow everything was different, since there would’ve been someone willing to step up and marry her, if only to collect that fine looking cow as well.

The only hope we have left is if the calf is still alive. Pray God it didn’t occur to him to follow his mother into the river. Because if he did, my sister Tacha is this close to becoming a whore. And that’s not something my mother wants.

My mother doesn’t know why God punished her so much by giving her daughters like that, when in her family, from her grandmother on down, no one’s ever been a bad person. They were all raised with the fear of God and were fully obedient, never disrespecting others. Each one of them was like that. Who knows where those two daughters of hers could’ve learned such bad behavior. She doesn’t remember. She spins through all her memories but can’t figure out where she went wrong or what sin she committed to give birth to one daughter after another with the same bad habit. She can’t remember. And every time she thinks about them, she cries and says: “May God help them both.”

But my father claims there’s no remedy for any of it. The one in danger is the one still at home, Tacha, who keeps growing and growing like an ocote pine shoot and whose breasts are beginning to show and promise to be just like those of her sisters: pointy and firm, but with just enough bounce to call attention to themselves.

—Yep —he says—, she’s gonna be an eyeful wherever she goes. And things are gonna turn out bad; the way I figure it, this is gonna turn out bad.

That’s what’s got my father worried sick.

And Tacha cries as she realizes her cow won’t be coming home because the river has killed it. She’s right here, by my side, wearing her pink dress, gazing down at the river from the barranca, unable to stop crying. Streams of dirty water run down her face as if the river had made its way inside her.

I hold her tight hoping to comfort her but she doesn’t understand. She cries harder. A noise drifts out of her mouth like the sound of the river scrapping against its banks, making her tremble and shudder all over, while the swell just keeps growing higher. The taste of decay coming up from the river sprays across Tacha’s drenched face, and those two little breasts of hers move up and down, nonstop, as if just now they’ve begun to fill out and lead her toward perdition.

__________________________________

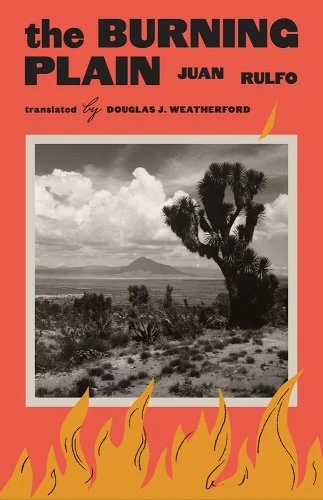

From The Burning Plain by Juan Rulfo, translation by Douglas Weatherford. Used with permission of the publisher, University of Texas Press. Translation copyright © 2024 by Douglas Weatherford.