Beauty After Brutality: On Healing and Reclaiming My Existence in the Wake of Racial Trauma

Anita Sethi Takes a Journey of Self-Discovery Through the Pennines

I was on a journey through northern England in early summer 2019 when I became the victim of a hate crime, when a man attacked my right to belong here, with words that hurt the very heart of me. The North is my home, having been born and bred in Manchester—the TransPennine Express train even passed through the city on its route from Liverpool to Newcastle. The hate crime was a vicious attack on my right to exist in a place on account of my race. I was called “Paki cunt” and told to “get back on the banana boat” and “go back to where you’re from”—and yet this country is where I belong.

Hate crime is on the rise in our hostile environment. After the attack some advised me to stop traveling alone due to the dangers, and I experienced panic attacks and anxiety at the thought of traveling by myself. But I was intent on not letting a hate crime stop me moving about freely and without fear in a country where I belong. I was eager to continue traveling alone as a woman, asserting my right to exist.

One day I was looking at a map of the North and there, along the route of my train journey, falls the Pennines, “the backbone of England,” with its nature reserves, national parks, and Areas of Outstanding Natural Beauty (an area of countryside designated for conservation due to its significant landscape value). My heart quickened as I looked at the miniature mappings of its mountains and rivers. The TransPennine Express journey had run a route tantalizingly close to such Pennine areas, but it would take walking and local railways to fully explore it. I longed to journey through the natural landscapes of the North, transforming what began as an ugly experience of hate and exclusion into one offering hope and finding beauty after brutality.

Go back to where you’re from. This is where I’m from. I’m from the North. The glorious North. Our emotional connection with certain places runs deep and forceful as a river, and during and after the hate crime I felt how profound my connection was with the North. Although a racist had viciously told me to leave, I felt a magnetic pull drawing me back—not to get further from it but even deeper into it.

My journey is one of reclamation, a way of saying, to adapt the Woody Guthrie song title, “this land is my land too” and I belong in the UK as a brown woman, just as much as a white man does. Journeying through the so-called backbone of England also feels symbolic, a way of showing backbone myself and that I will not let having been the victim of a race hate crime curtail my movements through the world, despite the trauma and panic attacks that followed.

The nature of trauma is that it lives on after the traumatic incident. The man who racially abused me was arrested, charged, pleaded guilty and was convicted of a racially aggravated public order offense, using threatening, abusive, insulting words and behavior. After I heard my abuser had pleaded guilty, I felt the oxygen return to my lungs. But in the days and weeks that followed, I still experienced anxiety attacks, feeling the room closing in on me as my breathing became rapid and my heart pounded. I saw the man’s face flash through my mind. I felt a crushing pain at the suggestion that I had no right to exist in a place that is my home. At my lowest ebbs I wanted to cease existing. When I walked up through the carriages, the man had threatened to set fire to me. I had nightmares about choking on smoke. Sleeplessness left me exhausted. Even walking the streets of the city, I felt a sense of claustrophobia. That year I’d been racially abused twice while walking the streets, in Nottingham and London.

As my claustrophobia grew, I began to long for wide open spaces, to breathe freely in the great outdoors. I hungered for greenness.

I began to devour more and more maps of the Pennines and plot out a route, reading up about the Pennine Way, Britain’s oldest long-distance footpath, which runs for 431 kilometers through the backbone of Britain. This path was the idea of the rambler Tom Stephenson who, in 1935, wrote about how he yearned for “a long green trail” like those of the John Muir Trail through the Sierra Nevada mountain range and the Appalachian Trail in the eastern mountains of the US. I also saw that the Pennine range is not confined to the Way but stretches from the Peak District, up through the Yorkshire Dales and into the North Pennines, fringed by the foothills of the Lake District, with a westerly outpost in the Forest of Bowland.

The nature of trauma is that it lives on after the traumatic incident.

I zoomed in on a map of the Peak District, where the Pennine Way begins, and where the North begins; its border. How glorious to glimpse a place named Hope. It’s there I wanted to start my journey, walking through Hope Valley. The night before the hate crime, I had happened to stay in a place called Hope Street Hotel on Hope Street in Liverpool—my actual experiences turned out to be profoundly allegorical. Since then I tried to channel hope throughout, drawing on it at my lowest ebb.

I felt strongly that journeying again through the North had something to offer me, and I wanted to follow that gut instinct. Places where traumatic events occur take on even greater significance; they become a part of us, a deep wound in us, often paradoxically drawing us back to the wounded place to understand something about it, to transform it into a place of empowerment—and that’s how I felt about that TransPennine Express journey and my journey of reclamation through the Pennines.

*

One day in mid-summer, I finally make a move. I get the Hope Valley line from Manchester, reopened after storm closure. I see flashes of purple rosebay willowherb through the window. I step off the train in Edale, the gateway to the Pennines, and feel the noise of the city fall away. As the train engines fade, silence envelops me, but for birdsong. I had been living in a flat on a busy main road, and it is particularly welcome to feel a deep quietening both in the outer world and in my head. I breathe in fresh air.

In a cafe called Penny Pot I sip sweet tea while looking at maps left on the table. A volunteer from the National Trust sitting at the next table sees me marveling at the maps and tells me more about Kinder Scout moorland plateau and nature reserve. This part of the countryside is about access and the right to roam, as it is here that the Kinder Scout Mass Trespass of 1932 happened, which helped to open up access to the countryside. Hundreds of walkers who were mainly from Manchester trespassed en masse on what was then private land and walked from Hayfield to Kinder Scout, asserting their right to exist in places from which they were excluded. Kinder Scout was at the time used to keep grouse for rich landowners.

The walk was celebrated in the folk song “The Manchester Rambler” by poet and folk singer Ewan MacColl, who marched during the protest and knew that walking could be a radical and political act and lead to change; that walking could be a way of saying: I belong here.

The Kinder mass trespass sparked a wave of transformation: three weeks later, 10,000 ramblers held a protest for the right to roam at the nearby limestone gorge of Winnats Pass, launching a movement that ultimately led to the creation of the first national park in 1951, the Peak District, and to the establishment of the Pennine Way and other long-distance footpaths. But it was not until the year 2000 that freedom-to-roam legislation was passed, securing walkers’ rights to travel through open country—just two decades ago. I feel how far there still is to go for all to feel safe and free and welcome while walking in the world.

I think about the deep wounds in places and in people, and how they might be healed.

A National Trust leaflet in the cafe explains about the Be Kinder walking trail, an initiative from Jarvis Cocker and Jeremy Deller, both whom I later run into at the cafe: “The self-led walking trail encourages people to think about the importance of being kind to this incredible natural habitat, as well as honoring the individuals who fought for our rights of way; allowing future generations to enjoy and protect this spectacular landscape for years to come.”

I had known little about this history when I boarded that Hope Valley line train into Edale; what a symbolic place it is to walk through as I assert my right to roam through the world.

Learning more about the North, my sense of place and identity deepens. As I walk through the moorland I feel more than ever that pioneering spirit from Manchester, and how walking is still a radical and political act.

The Pennines are an important water catchment area with many reservoirs in the headstreams of river valleys. The peat moorlands—landscapes of dark, rich peat soil which provide much of our drinking water—died off due to industrial pollution, poisonous gases destroying vegetation and damaging the peat. Hundreds of hectares are being brought back to life by conservation and restoration initiatives such as dams on the Kinder plateau, rewetting the moor and helping heather to flourish, and thousands of trees and cotton grass plants have also been planted, benefiting biodiversity. Another extraordinary species helping to bring the moorland back to life are sphagnum moss plants, and millions have been planted by volunteers. In damp areas the vivid green plants grow, taking in carbon dioxide, storing water and enabling habitats for other wildlife such as bird populations to flourish—so astonishing is sphagnum moss that it is able to hold twenty times its weight in water.

Sphagnum moss was used in the First World War as a wound dressing due to its antiseptic properties; it is now healing the deep wounds in the landscape created by erosion and pollution that left bare peat exposed. But these crucial upland landscapes are threatened due to climate change, the species and habitats that live here highly sensitive to environmental changes. Should climate change continue at its current rate, peat moorlands would be decimated, woodlands suffer drought, rivers and streams dry up, and creatures which make a home here such as curlew and lapwing be at risk of extinction.

I think about the deep wounds in places and in people, and how they might be healed.

I think about how we care for each other and for the land in which we live.

I think about being kind to each other, ourselves, and to the earth through which we walk. I had experienced kindness as well as cruelty on that train journey during which I was racially abused and am keen for it to be kindness that ultimately triumphs.

I feel a defiance to those who would have me disappear, a desire to keep on forging a place for myself in the world.

I continue to walk through the Kinder Scout moorland plateau, following “trig points” used to measure the heights of mountains. I see butterflies—a brown angus, common blue, marbled white, red admirals, bright orange-and-black painted ladies and small tortoiseshells. I see creatures of many colors flutter by, oblivious to me. I relish being in the non-judgmental world of nature. I relish learning the new names of places and creatures, letting the beauty of them take the sting out of the abusive words I was called. I look out for rare wildlife like bilberry bumblebees, which started to return when the moorland began to come back to life.

The world opens out and my sense of claustrophobia lifts, as I breathe deeply. My anxiety no longer contracts the world to the size of a train carriage. Through walking and engaging with the world around me, my thoughts are shifted from anxious ruminations. Soon I am entirely alone in fields of flowers. I lie down in the grass and begin to weep. I savor these moments being close to the earth, a part of it. I continue on the train to a place I’ll be staying that evening.

“We will shortly be arriving at Hope,” says the train conductor. Then, a little while later: “This is Hope.”

This is hope. This is what hope feels like. This is what it’s like to be in a place of hope, acknowledging the existence of pain and panic but pushing through it. Gazing out over the valley from on high, I look back over my life and at other times when I have experienced abuse and either did not speak out about it or did report it but was not taken seriously. I realize how much hatred can become internalized, become self-loathing.

Walking through the world, I feel those emotions shift and lift. Walking does wonders for my wellbeing, and I walk until I can feel my limbs, the bones in my body, my heart beating, telling me I’m alive, I exist, and I begin to relish existing.

I realize how much my anxiety has been about my sense of place in the world. I feel a defiance to those who would have me disappear, a desire to keep on forging a place for myself in the world.

I think back to the situation on the train and how it was standing up from my seat and walking through the carriages that had been defining, followed by talking with the train manager to report what happened—it had been standing up and speaking up. It had been walking and talking. I reported the hate crime as I wanted to do all I could to stop anyone else having to go through what I went through. In the days that followed, a desire grew in me to continue turning hope into action.

I’m hungry to continue my journey through the North. I feel my mind open out as I look forward to walking through the Forest of Bowland, rising up through the Yorkshire Dales, and the North Pennines.

“You may kill me with your hatefulness, but still, like air, I’ll rise,” wrote Maya Angelou. I want to continue rising, both geographically and emotionally.

My journey is far from over. I will not be silent. I will not stop speaking out, and I will not stop walking through the world, my home.

__________________________________

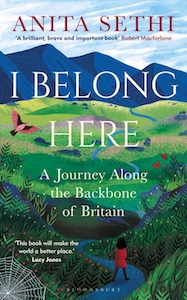

Excerpted from I Belong Here by Anita Sethi. Published with the permission of Bloomsbury Wildlife.

Anita Sethi

Anita Sethi was born in Manchester, UK where her love of nature first flourished in childhood, in wild urban spaces. I Belong Here is the first in her nature writing trilogy. She has contributed to anthologies including Seasons, Common People, and Women on Nature, has written for the Guardian, Observer, i, Sunday Times, Telegraph, Vogue, BBC Wildlife, New Statesman and Times Literary Supplement, and appeared on various BBC Radio programmes. She has been shortlisted for Northern Writer of the Year at the Northern Soul Awards and Journalist of the Year at the Asian Media Awards, and has judged the British Book Awards and Society of Author Awards. She has lived around the world including being an International Writer in Residence in Melbourne. Her career highlights include going birdwatching with Margaret Atwood in the UK's oldest nature reserve.