Beast Evolving: Fiction from the Australian Bushfires

A Short Story by Ben Walter

In early 2019, major fires threatened Tasmanian communities and ecosystems, blanketing the island state with smoke. This summer, millions of hectares have burnt on the Australian mainland, with months of the fire season still to run. Climate change scientists predict that in the coming decades, the continent will become hotter, drier and increasingly subject to devastating fire events.

–Ben Walters

*

Beast Evolving

“Can we keep him?” I asked. “Look at him run!”

He was bounding up the hills, fetching sticks to burn and lapping up pools of water in grass and trees, in the bodies of possums and roos. Here in the city, we’d never had a pet like this— dogs who rained their skittering claws on the bones of old brick yard, cats that ladled their bodies into the hollows of our arms. Fish that circled the dead-dry pond like orange lights telling us to wait and watch; to follow them slow before they blinked behind a rock. But we hurried past their brief lives, struggled with their names—which cat had brown ears? Did he run away to feral hills on the eastern shore? Was he taken in the night or taken in the day? Was it just a long, slim needle that found its way precisely to a vein that made him just a little quieter than he’d been?

“Can we keep him?”

It would be fine: we would be cosy when the frost found fame in the depths of June. We brought him home and locked him in a box, dark like the metal had charred; in the early mornings and fading afternoons we would bolt him in that cell to heat our homes, and all his smoke would cough up the flue and smear the sky. We would pull a couch near and watch his tricks—dancing in the corner and begging for kindling—and in the night he would curl low around a couple of split logs: dense, hard cushions that would yield to his press, powdering to ash. Later we would sic him on the waste wood pruned from withering apples and plums that the new flies had fleeced; shape him under a plate to sear the rare meat in the back end of swollen summers, seasons overweight and straining, sun fed, guts spilling into spring and autumn.

“Can we keep him?”

The bugger is he’s always getting out, leaping through the door and hurtling through the gate when the kids have left it swung, running over cars and snapping at feathers and fur, scraping back the peat with coal claws and plucking so much pine in bright bouquets of flame. We watch in booing crowds as he’s handed gum to gum, kicked long to the homes strung out drying in long lines of road, tackling their roofs and blistering the paint. Sure of his heft, measuring his height against the baking years graphed out in anxious charts, a beast evolving proud and strong—chest straining as his muscles flare—he grins a foul grin as he licks up leaves.

“Can we keep him?”

We try to put him down, splash water in his face to make him sleep; he gets up and snarls. We bury him in the yard, dig a kiln of clay to trap him as he fires, but he shatters the ceramic walls and races for the fence palings. We plug him up with drugs and knives, a new asbestos coat; he births huge litters and spreads his sparks across the state.

“Can we keep him?”

Here the footpaths are melting like old frost and the lawns have given up green; kids splash in dust and we water the tomatoes with drips of old sweat. Our city is a boiled egg with concrete cracks, and one tap can shatter the thinning shell. We take to the river for the miracle of fish; some set up home in its moat. Every winter we burn down the mountain and hope it will be enough. The harbour’s wider now but its hands stop nothing till the flames have bulled our china shop of homes and gardens. We remember the years that suburbs were clear-felled and gingerly rebuilt—there are signs, commemorations to old Lenah Valley, Sandy Bay—thin regeneration. We don’t get so attached. Parts of the city phoenix each year and we get to know the new bird rising as it learns the words and speaks to us anew: “hello cocky, hope you like it here!”

We bury him in the yard, dig a kiln of clay to trap him as he fires, but he shatters the ceramic walls and races for the fence palings.The whole city: our hearth and home. We dress in threads of fear like we’re being hunted: our lion cub that played and leapt and scratched us just a little has grown up and gone bush, gone wild. He’s bred in there and he’s coming back, and back, and the smoke is a blanket of new clouds forming shapes that none of us want to see, clouds that send the sun’s eye red and weeping, clouds that make our own eyes feel like gravel roads, clouds that paint the borders of our lungs, that leave us hunting for our homes and the track to safety, for our mothers, fathers and children lost in all that brown, all that white, lost in the bodies of cremated trees sent high; our heavens damned with the cyclone of seasons picking up speed, whirring weather leaving us on the bare beach gasping.

“Can we keep him?”

We heard that years ago the fires danced in tight squares, hemmed in by the patterns of roads, old burns and the rhythmic rain hammering their coffin lid down every season as the days closed in and the winds from the south flexed. This may have been a lie, some golden age tale when no gold flickered in the hills, when the wet came steady and long like a novel we read all year. Was this real or just a story? Maybe these were tree myths told in pages from their guts; maybe they were our myths, fictions we blew across the forests and forgot. Was there ever a time when half the year matched the other, when we didn’t cower under a blunt threat that waited for the wind, the jagged spark in the sky that was again an angry god that called for flesh to blaze?

What if there was? What if there were no dragons then? What if we were children once and some small part of our lives stayed that way, summers of bright skies and flowers in the bush that held our hands? What if the days were clear and we could breathe in them? What if our homes were firm homes that didn’t come crashing down when they were shouldered by a storm? What if we could walk all day in the streets and in the hills, never once looking over our shoulder or sniffing acrid notes in the air?

These days, we pat his orange feathers.

Always, he bites.

_________________________________________

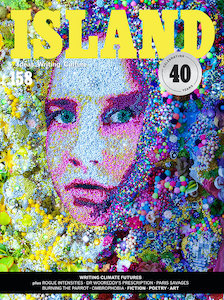

This story appears in the current issue of Island Magazine.