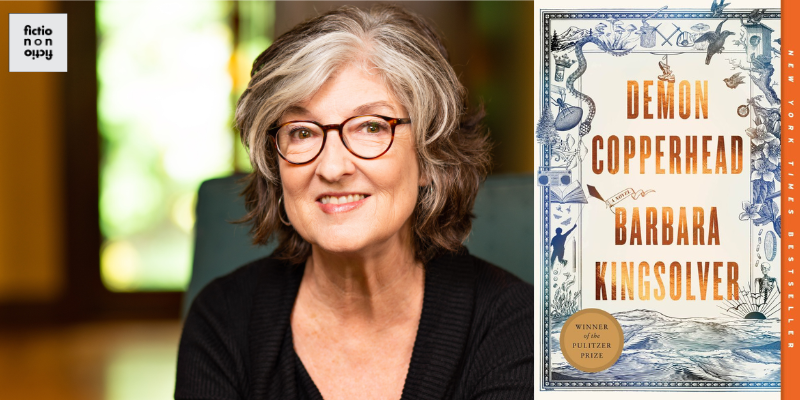

Barbara Kingsolver on Supporting Appalachian Women Recovering from Addiction

In Conversation with Whitney Terrell and V.V. Ganeshananthan on Fiction/Non/Fiction

Pulitzer Prize-winning novelist Barbara Kingsolver joins co-hosts Whitney Terrell and V.V. Ganeshananthan to discuss her support of Higher Ground, a long-term residence for women recovering from addiction. Kingsolver talks about Lee County, Virginia, which is both Higher Ground’s location and the setting for her wildly successful novel Demon Copperhead, which transforms Charles Dickens’ David Copperfield into a story of the opioid epidemic in Appalachia. Kingsolver explains how she came to use profits from the novel to found Higher Ground, as well as the local partnerships and conversations that made the project possible. She also reflects on Purdue Pharma’s exploitation of Appalachia; her views on ethical philanthropy; her worries about what the Big, Beautiful Bill will do to rural America; and her opinions on Vice President J.D. Vance’s authenticity. She considers how she developed the voices of her novel’s characters, and reads from Demon Copperhead.

To hear the full episode, subscribe through iTunes, Google Play, Stitcher, Spotify, or your favorite podcast app (include the forward slashes when searching). You can also listen by streaming from the player below. Check out video versions of our interviews on the Fiction/Non/Fiction Instagram account, the Fiction/Non/Fiction YouTube Channel, and our show website: https://www.fnfpodcast.net/

This podcast is produced by V.V. Ganeshananthan, Whitney Terrell, Hunter Murray, Janet Reed, and Moss Terrell.

Barbara Kingsolver

Demon Copperhead • Higher Ground Women’s Recovery Residence • Unsheltered • Flight Behavior • The Lacuna • Animal, Vegetable, Miracle: A Year of Food Life • The Poisonwood Bible • Pigs in Heaven

Others:

“‘I’ve dealt with anti-hillbilly bigotry all my life’: Barbara Kingsolver on JD Vance, the real Appalachia and why Demon Copperhead was such a hit” |The Guardian • Nickel and Dimed: On (Not) Getting By in America by Barbara Ehrenreich • Hillbilly Elegy by J.D. Vance

EXCERPT FROM A CONVERSATION WITH BARBARA KINGSOLVER

Whitney Terrell: We’re a podcast that talks about the intersection of politics and literature, and obviously this program [Higher Ground, a long-term living situation founded by Kingsolver for women recovering from addiction] is fantastic and important, but it’s an individual effort, right? We would have to give out a lot more Pulitzer Prizes and have a lot more bestselling novels in order to make this functional across the country. It made me think about the Big, Beautiful Bill that was recently passed that is going to cut Medicaid benefits for people by putting work requirements on them. I’m reminded of Barbara Ehrenreich’s book from the ’90s called Nickel and Dimed about how hard it is to work, and to work when you’re coming off of addiction just seems even harder. Obviously there’s a whole huge hole in the governmental safety net for this issue.

Barbara Kingsolver: There’s a huge hole in all of our governmental safety nets, as you know, and I’m really frightened about this big, ugly bill for reasons well beyond the difficulties of people struggling with addiction. It’s going to affect my life, a person as comfortable and well off as me. Our local hospital is probably going to close. I could end up being 100 miles from the nearest hospital. I don’t want to think about it too much, because I don’t want to have a heart attack.

WT: That would be a long drive then, if you had a heart attack.

BK: A real, long drive. It’s terrifying what this bill, and specifically the Medicaid cuts, will do to rural, rural health care, which was already stretched thin. Almost all rural regions in this country already have a shortage of doctors, healthcare workers, and hospitals. This is going to drive the stake through the heart. The small, compensatory package that they said will help support the rural hospitals—I’ve seen the numbers. It’s not even 10 percent of what we will lose. So we’re in trouble for all kinds of reasons. And I agree with you that I wish the government were doing this instead of me doing it. You know, with the money I have. But on the other hand, those guys are giving big tax breaks to wealthier individuals. So I can use that to give back. I can do whatever I can. But no,individuals shouldn’t have to be doing this. Our government should. Be looking out for people who have the greatest struggles. But it doesn’t. It just doesn’t.

WT: The Guardian article quotes you as saying that the social issues in Appalachia are the fault of big companies who came here to take something away and then came back with Oxycontin, to quote, “harvest our pain.” You’re quoting the article talking about Appalachians as being strong and self-reliant, their pride, and how the shame of addiction has played a role in the lack of treatment opportunities. You also talk about JD Vance, who was involved in that big, ugly bill, and his book Hillbilly Elegy as misrepresenting Appalachians. Could you talk about this exploitation you’ve seen of this area and what that has to do with class?

BK: Yeah, the simplest way I’ve figured out to explain Appalachia, to put it in a historical context, is that Appalachia has been treated as an internal colony of the United States. It was blessed and cursed with a lot of rich resources, starting with timber, mountains covered with lumber which was very valuable, and underneath were rich veins of coal, which fired the Industrial Revolution, which really built this country. But much like the Congo and other places that we can study as being victims of colonial exploitation, it was outside companies, extractive industries, that came in to take first the timber, then the coal. And they did it in a very controlling way, which is also kind of a colonial way of operating. Let’s just take the coal companies, which were the biggest employer through in the early part of the last century. They didn’t just own the mines. They owned everything. They owned the housing, the courthouse, the schools. It was not in the coal company’s interest to have any other opportunities for employment so they quite deliberately kept out textile mills and other furniture factories, the kinds of things that you see elsewhere in the southeast, outside of the coal regions, because they didn’t want people to have any choice about where they worked. It was also not in their interest to have a very educated or class mobile population, so they deliberately suppressed educational opportunities. That is a fact. I went to a public school in Eastern Kentucky that offered me no science, no math. I was a product of the remnants of that and it’s a structural problem that has remained with us, even as coal has died. There is still coal in the ground here, but it’s too hard to extract, and it’s not economically feasible because natural gas is cheaper. So they did this to us, they suppressed all other opportunities, and then left. That’s the story of Appalachia.

On top of that, we get the blame. My entire life, from the time I first stepped out of Appalachia, I’ve encountered the stereotype of the dumb hillbilly. We are blamed for our so-called backwardness, our educational challenges, our health challenges, our economic challenges, the high unemployment, all of these things. It’s convenient to say that they’re our fault. It fits in very nicely with this myth that there is no class in America, that anybody, if they work hard enough, and if they’re smart enough, can get ahead, which was really the message of J.D. Vance’s book: he went to Yale, he worked hard and he got out of there while his dumb hillbilly neighbors didn’t have enough ambition to do that. Just look at the guy. He’s not Appalachian. If he were a real hillbilly, he wouldn’t tell that story, because that is so unlike the way we tell stories here. I can tell you a lot of things about Appalachian culture, and one of them is that we are great storytellers, and another is that we always laugh at ourselves. We do not put ourselves above other people, for better and for worse. My whole life I heard, “It’s not the whistle that pulls the train, young lady,” and “Don’t go parading yourself around,” and “The tall weed gets cut,” and don’t get above your raisings. I’ve had to work on that. It’s not a real healthy sort of soup for a woman to cook in. But at the same time, this culture of modesty connects us with our people. We don’t put ourselves above others. Look at Vance. He’s not one of us.

V.V. Ganeshananthan: Before, you mentioned Purdue Pharma. There’s other players here, like the Sackler family. Some of these actors taking advantage of people in Appalachia come through in Demon Copperhead when, say, Demon’s mom is offered a pill that will keep her on her feet, Demon is offered pills for his injury, and June tells her father the drug is completely safe, and urges him to take one. There’s a lack of treatment and sympathy, as you mentioned before, and there are lots of organizations and nonprofits that purport to help but don’t succeed. In The Guardian article, you’re quoted saying, “Charity is a very loaded concept. It involves a power imbalance. It’s a person standing in a position of privilege saying, I will give this gift to you, and implicit is to help you become more like me. Everything about that is odious to me.” Given the culture that you were just describing, this culture of modesty and self-reliance, did you have to put a lot of thought into making Higher Ground a success, making it something people are willing to be involved in, before you helped fund it? I think about this as doing things with people, as opposed to for. I wonder if you could talk about how you think about ethical philanthropy and charity, what works and what doesn’t. Because, as you say, Vance purports to be doing good for a lot of people. We all know he’s doing harm.

BK: He is really hurting rural people. His whole project is really dangerous for the rural half of this country. But as far as how you go about helping, the thing that’s been done wrong historically—and we’ve seen this play out over and over again—is coming from a place of privilege or comfort or whatever advantage, into another place and telling people “This is what you need. I’m gonna fix you,” meaning give you opportunities to become more like me. It’s not only something people resent for all kinds of reasons—reasons of shame and power imbalance— it’s also just often inappropriate. It’s wrong. It doesn’t work, inappropriate technology. It’s the wrong stuff. I wrote a whole novel about that called Poisonwood Bible. The religion is wrong, the technology is wrong, the agriculture is wrong, the attitude is wrong. What works better—and you do see this increasingly in international aid organizations—is for people to go into a place and say, “Talk among yourselves, figure out what you need, come back to me with a proposal.” I’ve seen that model in organizations like Heifer International. I’ve done some work for them, and I’ve gone to visit communities where that really worked. It’s usually women who get together and come up with a plan and say, “Here’s what we need, and here’s how we can make it, and here’s how we can pass it on.”

So that’s what I did. I went over to Lee County, and I pulled together the friends I had over there who worked in the field of addiction and recovery. We had a big breakfast meeting at Denny’s, and I just said, “Go around the table, tell me what you do. Tell me what you think is needed.” And every single conclusion everybody reached is that we need recovery homes. And I didn’t know how to do that, so I said, “How do you do that?” And they said, “Well, we’ll talk to our friends, we’ll talk to the churches, we’ll talk to other organizations.” It was a very organic process. Once we figured out what was needed, I was able to buy the house because that was the starting point. Then it’s like all this goodwill needed a place to go, a focal point. So I opened the door, and it all poured in, and it’s still pouring in, and we still need a lot, you know? I mean, the needs are ongoing. I’m not looking at this as something that I’m gonna do by myself by any means, but I’m very happy to stay active, and it also matters to me that this is my home. I live here. I’m a Southwest Virginian, so it’s not like I had to go over the mountain and discover mountain people. I am one. I come from here.

Transcribed by Otter.ai. Condensed and edited by Rebecca Kilroy. Photograph of Barbara Kingsolver by Evan Kafka.

Fiction Non Fiction

Hosted by Whitney Terrell and V.V. Ganeshananthan, Fiction/Non/Fiction interprets current events through the lens of literature, and features conversations with writers of all stripes, from novelists and poets to journalists and essayists.