Banishments Inside of Banishment: How Global Capitalism Destroys Our Connection to Place

V (formerly Eve Ensler) Considers Dislocation, Community, and Connection

2016

The first time I awakened to the depth of my own disassociation from place was in Rawalpindi, Pakistan, during the years of the Bosnian War. I had gone to a refugee camp there to meet and interview a group of Bosnian refugees who had been taken in by the Pakistani government, generously offering sanctuary to fellow Muslims. The people were from small villages in Bosnia that had been under siege by Serbian forces. Some had lost family members, some had been raped. Some were recovering from violent injuries.

Everyone was traumatized, uprooted, and dislocated. The conditions of the camp were very basic and difficult: no clean water, overwhelming heat, lots of illness. Hardly anyone spoke English. The customs and even the practice of religion in Pakistan were foreign to Muslims from Europe who up until the war had never been deeply religious or aware of themselves as Muslim. The Bosnians were sick, lonely, depressed, but what possessed them all was almost a viral homesickness.

There were about five hundred people there and many were from a town called Donji Vakuf in central Bosnia. An older man from the town had decided to do something to relieve his community of their desperate longing for home. He built a model of Donji Vakuf with streets and mosque and churches, cafés and town halls and a tower that stood in the center with clocks on all four sides so the people coming from every direction would know what time it was. It was a stunning replica, laid out on the stone floor.

The group would make a strong pot of Bosnian coffee, grab their cigarettes, and sit around the model talking, complaining, and gossiping as if they were returned to their precious town. It seemed to bring them back to life. They would point to various spots on the model, and this would instigate reminiscences and stories that would fill the morning and the afternoon.

I was astonished to see the depth of their attachment to a place and how even being near a facsimile of it restored their good natures and happiness.

People mistake nationalism for love of place. Nationalism is dedication to an ideology, a righteousness, a patriotism that declares one nation better than others. Loving a place has nothing to do with hierarchy or competition.

One day the community discovered the tower of the replica was missing. There was a young woman in the camp who had a serious case of epilepsy. It was very hot in Pakistan and each time she went into the sun she had gone into multiple seizures, so she had been relegated to her bed with the shades pulled and had become seriously depressed. It was eventually discovered that she had taken the tower into her bed and had been sleeping with it, clutched to her chest like a puppy. It was bringing her deep comfort and had lifted her spirits immensely. The community decided she needed the tower more than they did.

I was in awe, and to be honest, perplexed. I had never known anything resembling such a love and attachment to a place. I had never missed a place.

Up until this point in my life, place was something I fled and was fleeing. Place was where bad things happened. Place was the castle of a madman where you were caught for eternity, at his whim, delivered daily into his cruelty with no reprieve. Place was anxiety and terror. It held the nightmares and the smells of abuse. Staying still in one place would allow him to find you. I did not want to be found.

I wanted to move and not stop moving. I wanted to be as far from the murderous suburbs as possible. I wanted a permanent exit from normal and family and home. I was a psychological nomad, never landing physically or emotionally, never staying, never truly available, frustrating lovers and partners who sensed they could never have me even when I was there, and the truth is, they couldn’t. I romanticized my exile, made myself believe I was the one who had determined it, called it independence, freedom. To some degree that was true, but ultimately underlying it all was fear of place, terror of settling, of being had. On the deepest level it wasn’t a real choice. Fight or flight. I was in a life of flight.

The first real apartment I lived in in New York City, I moved the bed into the living room, as I hated bedrooms. I hated that room tucked away in the dark where most of the violations of my childhood had occurred. I hated dining rooms where most of the beatings and assaults had begun. I never saw where I lived as the place I stayed. I saw it like a train station, something I was passing through, a place that kept my things when I returned from escaping. It is why the city was so appealing. Although it is a location, it was a transient one for me.

The earth is where we draw our strength. The community is where we are shaped and held, validated, known and protected.

What determines place? Community perhaps, nature, a sense of belonging, commitment to the people who live with you and by you, commitment to be a good steward to the earth that supports you. I think of the astonishing poem by David Whyte. I have this particular verse painted on my kitchen wall.

This is the bright home,

in which I live,

this is where

I ask

my friends

to come,

this is where I want

to love all the things

it has taken me so long

to learn to love.

This is the temple

of my adult aloneness

and I belong

to that aloneness

as I belong to my life.

People mistake nationalism for love of place. Nationalism is dedication to an ideology, a righteousness, a patriotism that declares one nation better than others. Loving a place has nothing to do with hierarchy or competition. The depth of love for your place organically connects you to all places. Your place in your streets, on your block, in the forest, in the web of life, which is part of the whole organism of life. This organism is without boundaries or borders. The deeper you ground in one place, the more connected you are to all places. The deeper you fall in love with trees around you, the deeper your love for all trees.

John Berger wrote:

This century, for all its wealth and with all its communication systems, is the century of banishment. Eventually perhaps the promise of which Marx was the great prophet, will be fulfilled, and then the substitute for the shelter of a home will not just be your personal names, but our collective conscious presence in history, and we will live again at the heart of the real. Despite everything I can imagine it.

Our cities are flooded with the banished. Those regarded as problems or black sheep in their families, ostracized and fleeing hate and punishment, fleeing persecution, war, poverty, hatred, landlessness, searching for jobs and safety.

In a global capitalist system, every place is for ransacking and conquest, every place for potential expansion and exploitation. Place becomes commodified, a thing to be acquired, serving the interests of the corporations and the very rich. And as lands get destroyed by imperialistic wars, climate crisis brought about by plundering through extraction and devastating pollution of waters, earth and air, and massive unemployment bought about globalization, more people are forced to flee in search of safe ground and jobs.

Global capitalism not only escalates a mass exodus from place, it relies on it. When people are separated from their homes, from their bases, families, from their grounding in culture, farms, their rivers, their tradition, community, and continuity, they are destabilized, vulnerable to exploitation, oppression, death, and tyranny. The earth is where we draw our strength. The community is where we are shaped and held, validated, known and protected.

Today, as I write, the Trump administration has issued a ban on Muslims coming into the United States from seven Muslim countries, Iraq, Syria, Iran, Libya, Somalia, Sudan, and Yemen. One of the underpinnings of America, a country made of immigrants, has been our willingness to offer people throughout the world safety and harbor, a place to land and rebuild.

Now the corporates, the racists, and the rich who rule America are devastating this as well. And to heap insult upon injury, most of the countries we are banning are countries we have been part of destroying through imperialist interventions. We are banishing those we are responsible for bombing. Double banishment, dystopian banishment. Banishments inside of banishment.

______________________________________

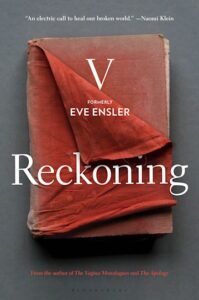

Excerpted from Reckoning by V (Formerly Eve Ensler). Used with the permission of the publisher, Bloomsbury. Copyright © 2023.

V (formerly Eve Ensler)

V (formerly Eve Ensler) is a Tony Award–winning playwright, author, performer, and activist. Her international phenomenon The Vagina Monologues has been published in 48 languages and performed in more than 140 countries. She is the author of The Apology, the NYT bestseller I Am an Emotional Creature, the highly praised In the Body of the World, and many more. She is the founder of V-Day, the global activist movement to end violence against women and girls, and One Billion Rising, the largest global mass action to end gender-based violence in over 200 countries. She is a co-founder of the City of Joy, a revolutionary center for women survivors of violence in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, along with Christine Schuler Deschryver and 2018 Nobel Peace Prize winner Dr. Denis Mukwege. She is one of Newsweek’s “150 Women Who Changed the World” and the Guardian’s “100 Most Influential Women.” She lives in New York.