Balzac Tried to Buy a Waistcoat for Every Day of the Year (and Other Revelations of Parisian Fashion)

On the Absurd and Wonderful Sartorial Habits of a Great Writer

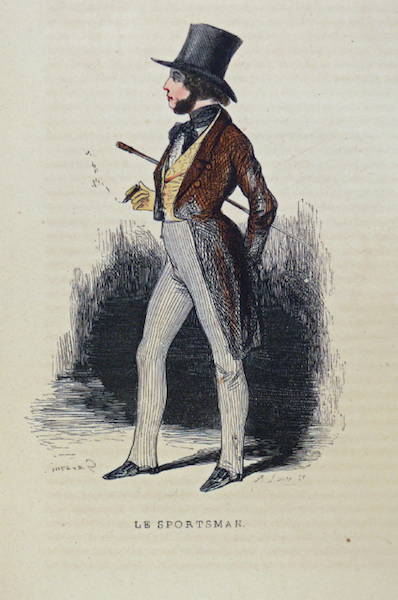

“Dress is the expression of society,” wrote Honoré de Balzac in his “Treatise on the Elegant Life,” which appeared in the royalist fashion magazine La Mode in 1830. The greatest novelist of the Restoration and the July Monarchy, Balzac was also a prolific journalist, who wrote little works such as Physiologie de la toilette, subtitled “On the Cravat, considered in itself and in its connections to society,” and contributed to veritable encyclopedias, such as The French Painted by Themselves (1840–42), which described Parisian types from the grisette to the femme comme il faut, and from the rag-picker to the rentier. (His contemporary, Sulpice-Guillaume Chevalier, better known as Gavarni, created images of these types, which form a visual complement to Balzac’s work.)

Balzac is a very important source for understanding the role of fashion, both in society at large and in high society. Although he may have over-estimated the importance of dressing elegantly as a means of rising in society, he was correct in observing that Parisian elegance was inextricably connected to the redefinition of class and status in the modern era. Typically, he simply appropriated the aristocratic particle “de” as part of his personal self-promotion. As Shoshana-Rose Marzel observes, “Even if Balzac distinguishes aristocratic milieux from other rich milieux, from the vestimentary point of view, these differences are more the fruit of a personal investment than of a knowledge reserved to a social class.”

Balzac was born at Tours in 1799, the year of Napoleon’s coup d’état and came to Paris when he was 20. Like so many of his characters, he arrived wearing the provincial clothes that his mother had given him. Within a few years, however, he began ordering his clothes from Buisson, a well-known tailor on the rue de Richelieu: one month a walnut-colored redingote, a black waistcoat, steel-gray pantaloons; the next month black cashmere trousers and two white quilted waistcoats; later 31 waistcoats bought in a single month, part of a plan to buy 365 in a year. By the end of 1830, he owed his tailor 904 francs and his bootmaker almost 200—twice the sum he had budgeted for a year’s food and rent. But he believed that good clothes were a necessity for an ambitious young man from the provinces out to conquer Paris.

Paul Gavarni, Illustration for La Mode (c. 1830).

Paul Gavarni, Illustration for La Mode (c. 1830).

Unfortunately, his contemporaries agree that Balzac was appallingly poorly dressed. According to the Baroness de Pommereul, Balzac was a fat man whose badly made clothes made him look even fatter. The painter Delacroix criticized Balzac’s sense of color. Madame Ancelot said that when Balzac was working on a book, his clothes were neglected and even dirty, and when he went into society he adopted an elaborate and bizarre style “which astonished his friends and which he laughingly called an advertisement.” He was famous for working in a slovenly dressing-gown, and strolling along the boulevards carrying a magnificently eccentric jeweled cane.

Captain Gronow, biographer of the famous Regency dandy, Beau Brummell, was surprised and disappointed at Balzac’s appearance: “Balzac had nothing in his outward man that could in any way respond to the ideal his readers were likely to form of the enthusiastic admirer of beauty and elegance in all its forms and phases . . . [He] dressed in the worst possible taste, wore sparkling jewels on a dirty shirt front, and diamond rings on unwashed fingers.” Balzac himself admitted that only the social elite, who did nothing, had the leisure for la vie élégant, but he also argued that the artist (such as himself) “is not subject to laws” and could, therefore, be “elegant and slovenly in turn.”

Balzac might have been fat, slovenly, and vulgar in real life, but he knew what the elegant man was supposed to look like, and he created a host of dandy characters, from Charles Grandet and Henri de Marsay to Eugène de Rastignac and Lucien de Rubempré. Indeed, Balzac created more than 2,000 characters, and he described the clothing of almost every one of them in minute detail. He shows his characters’ vanity, their embarrassment, their self-consciousness, and their obliviousness to their clothed appearance, but he never once implies that they should concern themselves with more “important” things.

Clothes were very important to Balzac. Not only do they place a character or type within a particular social and temporal setting, they also express his (or her) personality, ambitions, inner emotions—even destiny. “The question of costume,” argues Balzac, “is one of enormous importance for those who wish to appear to have what they do not have, because that is often the best way of getting it later on.”

*

According to the scientific theories of the early 19th century, human society could be analyzed according to a biological model: there were literally different “species” of people, whose outward appearance corresponded to their inner character, just as the lion’s teeth showed his carnivorous nature. The characters in Balzac’s novels, like the personages in popular physiologies, were intended to correspond to the new urban types that flourished in the growing capital: the lion, the employee, the rentier (or stock-holder, who lived off his investments). Naturally, these people existed and, to a considerable extent, did wear distinctive styles of dress, although this is subject to a degree of satiric exaggeration.

In the human genus, there were “a thousand species created by the social order,” wrote Balzac. And one of his collaborators noted that there were “innumerable varieties” of employees alone. But they insisted that a glance at his badly tailored suit and baggy trousers was sufficient to say, “Voilà un employé.” The appearance and habitat of each species were duly noted: “The rentier stands between five and six feet in height, his movements are generally slow; but Nature, attentive to the conservation of weak species, has provided the omnibus by the aid of which the majority of rentiers transport themselves from one point to another in the Parisian atmosphere, outside of which they cannot live.” His clothing receives the same treatment: “His large feet are covered with shoes that lace up, his legs are endowed with trousers in brown or in a reddish color; he wears checked vests of mediocre value. At home, he terminates in umbelliform caps; outside, he is covered by hats costing 12 francs. He is cravated in white muslin. Almost all these individuals are armed with canes.

Of course, Balzac himself was always armed with a cane—although a rentier who spent only 12 francs for a hat would never have carried a cane with a golden head studded with turquoise. Workers wore caps, while the bourgeoisie wore hats, but there were hats and hats. According to Balzac, a bohemian appointed to political office (under the July Monarchy) immediately changed his low, wide-brimmed hat in favor of a new hat whose design was “truly juste-milieu.” Retired imperial soldiers “took care to have their new hats made in the old military style,” reported another writer. Even without his hat, the Baron Hector Hulot was immediately recognizable as a veteran of the Napoleonic army: he stands with “military erectness . . . his figure, controlled by a belt,” wearing a blue coat with gold buttons, “buttoned high.” Dominated by his erotic obsession with Valérie Marneffe, Hulot is lured into abandoning all personal and sartorial self-respect, and ends up in filthy rags, wearing, perhaps, one of those shabby old hats worn by rag-pickers and sold on the street by the old-clothes man.

“Unfortunately, his contemporaries agree that Balzac was appallingly poorly dressed.”Clearly, the audience for Balzac’s novels was able to recognize the types portrayed and to appreciate (better than we can today) the nuances of their dress. We may recognize, for example, that Cousin Bette dressed like a prototypical “poor relation” and “old maid” in a hodgepodge of cast-off garments and vestimentary bribes. But the modern reader may not fully appreciate the significance of Bette’s expensive yellow cashmere shawl and her black velvet hood lined in yellow satin.

Who now remembers that yellow was traditionally the color of treason and envy? Yet, great as he was, Balzac could be over-simplistic in his use of clothing symbolism. Lucien’s mistress, the actress Coralie, openly proclaims her sexual passion when she first appears wearing red stockings. Conversely, Hulot’s virtuous and long-suffering wife habitually wears the white of purity. And the saintly prostitute, Esther Gobseck, dresses for her meeting with the banker, Nucingen, in bridal white, even wearing white camellias in her hair. Real people do not utilize such a transparent and unidimensional language of clothes, any more than bad guys wear black hats. Much more subtle is his description of the Princesse de Cadignan dressing in shades of gray, so as to convey (falsely) to d’Arthez that she had renounced the hope of love and happiness.

Balzac certainly knew that clothing can lie. Indeed, he pays particular attention to the clothing of people who are not what they seem to be. Valérie Marneffe has four lovers, but she usually dresses like a respectable married woman, in simple, tasteful fashions. According to Balzac, “These Machiavellis in petticoats are the most dangerous women”—far more to be feared than honest demi-mondaines. His villains frequently resort to disguises. In Lost Illusions, the master criminal Vautrin is dressed as a Spanish priest: his hair was “powdered in the Talleyrand style. His black silk stockings set off the curve of his athlete’s legs.” In César Birotteau, the repulsive scoundrel Claporan normally wears “a dirty dressing gown, opening to show his undergarment,” but when he goes into society he wears elegant clothes, perfume, and a new wig. Like criminals, police spies adopt innumerable disguises: In A Harlot High and Low, we learn that Contenson “could turn himself out stylishly when there was need,” although “he cared as little about his everyday dress as actors do about theirs.

Fashion plate, Journal des Dames et des Modes (1832).

Fashion plate, Journal des Dames et des Modes (1832).

The streets themselves were a kind of theater. In his “History and Physiology of the Boulevards of Paris,” Balzac argued that “Every capital has its poem . . . where it is most particularly itself.” For Paris, it was the boulevards. Whereas, “in Regent Street [there is] always the same Englishman and the same black suit, or the same Macintosh!,” in Paris there was . . . “an artistic and amusing life of contrasts.” On Parisian boulevards, “one observes the comedy of dress. Many men, many different outfits, and many outfits, many characters!” On the boulevard St. Denis alone, one saw “a variety of blouses, torn suits, peasants, workers, lunatics, people who make of a not very clean toilette, a shocking dissonance, a very conspicuous scandal.” If some places revealed “the inelegant and provincial masses . . . badly shod,” other stretches of boulevard were “a dream of gold,” jewels, and rich fabrics, where “everything . . . over-excites you.”

The 550 meters of the boulevard des Italiens were especially fashionable and animated. According to Edmund Texier, “The promenade [along the boulevard des Italiens] . . . is a tranquil river of black suits, sprinkled with silk dresses . . . a world of pretty women and gentlemen who are sometimes handsome but more often ugly or uncouth.” A lion with wild and messy hair was followed by a well-dressed man trying to pose as a baron. “The dandy displays his graces, the lion his mane, the leopard his fur—all exhale the smoke of ambition.” The “majority” of clothes “have not been paid for.” Meanwhile, not far away, “The lions of the boulevard de Gand, more sober than their brothers from the Sahara, live exclusively on cigars and meaningful glances, on politics and idling. Hunger . . . pushes them . . . to the asphalt, theater of their exploits.”

__________________________________

From Paris Fashion: A Cultural History, by Valerie Steele. Courtesy Bloomsbury, copyright 2017, Valerie Steele.