Bad Girl Debutantes, Rebellious Nuns, and a Pregnant Moose: 5 Books You May Have Missed in March

Bethanne Patrick Recommends Pamela Hamilton, Marj Charlier, and More

I’ve been writing this column for nearly six years, and after years of trying to choose the five most stellar books of fiction that deserve more readership, patterns are starting to emerge (either that, or COVID isolation has gotten to me). Last month, I featured five thrillers in translation. This month, I’m highlighting five novels with unusually affecting female characters. A bad-girl debutante, a bewitching adolescent lesbian, an expatriate trauma survivor, a revolutionary medieval nun—and a moose. Yes, you read that right. That’s why I wrote “female characters” instead of “women protagonists.” But I think you’ll agree with me, so read on. . .

*

Pamela Hamilton, Lady Be Good

(Koehler Books)

It’s one of Frida Kahlo’s most arresting works, this image of a woman upside down, falling from the top of a building, while her already dead body lies on the ground at the bottom. “The Suicide of Dorothy Hale” was painted on commission by Clare Booth Luce, who had intended to present a portrait to Dorothy’s mother. Horrified by the finished painting, Luce succeeded in having some small changes made. But nothing could change Dorothy’s sad history, or the circumstances of her death. Once the bad-girl debutante of Pittsburgh, Hale went on to become a Ziegfeld showgirl, Hollywood star, and friend to many of the rich and famous of her time, including Fred Astaire, Gertrude Stein, and James Roosevelt—none of whom could protect her from her own proclivities and despair. When she died, at 33, she was penniless and alone. But journalist and producer Hamilton has brought her back to center stage in this carefully imagined portrait in words instead of oils.

Forsyth Harmon, Justine

(Tin House Books)

Forsyth Harmon’s illustrations that grace the pages of Melissa Febos’s wondrous Girlhood also feature in this, Harmon’s debut novel about 1990s Long Island girls. Her eerily accurate but also slightly askew sketches of Diet Coke cans, bikinis, and Dannon yogurt tubs add a great dimension to the coming-of-age narrative, rarely matching up exactly with events but haunting every step of protagonist Ali’s way. The Justine of the title is another local teenager who works as a supermarket cashier; from the blondish roots of her black bob to the tips of her skinny toes, her spooky qualities attract and repel so fiercely that Ali immediately applies for her own job as a cashier. She starts to hang out with Justine, learning the other girl’s shoplifting secrets (put your old shoes back in the shoebox and walk out of the store like you mean it) and anorexic metrics (keep calories below one thousand per day and consume mostly protein). Finally, a book about remembering your first serious crush that’s not about fulfilling any cishet tropes.

Amanda Dennis, Her Here

(Bellevue Literary Press)

A young woman has disappeared, and her mother asks a dead friend’s daughter to reconstruct the young woman’s life from her diaries, in the hopes of stumbling on clues to where she may be. It’s a premise that would be a stretch for any novelist, but in her experimental debut Amanda Dennis wields that stretch the way a candymaker pulls and thickens ropes of sugar on hooks. Ella’s journals lead Elena on a hunt that spirals toward madness, especially as Elena grieves the recent loss of her own mother. Does writing equal identity? Reading what Ella has written leads Elena into the other woman’s consciousness—as reading fiction does—and Elena’s entanglement with the material leads her to consider whether or not we can actually, ever, reconstruct a person from words, spin something substantial from mere symbols on a page. And yet, and yet, the Ella who begins to emerge from her own writing does have substance, enough so that without spoiling anything, it’s possible to say the ending has satisfying heft.

Marj Charlier, The Rebel Nun

(Blackstone Publishing)

In 589 CE, Clotild, the illegitimate daughter of the King of France, led a group of fellow nuns in an armed rebellion against the excesses of the Roman Catholic church. Women, whose choices were already limited, did have some power in the early church, even acting as clergy and marrying priests. However, powerful men began to change those roles, ousting women from clerical status and arguing for priestly celibacy. Clotild, who wished to be her cloister’s next abbess, takes action when a bishop blocks her appointment. Charlier, a former reporter for The Wall Street Journal, brings a journalist’s eye to history; she’s less interested in developing Clotild’s character than in helping us understand her motives, which are legion. One of the Bishop of Poitiers’ tactics to show his displeasure is to cut off supplies to the Monastery of the Holy Cross (the term “convent” not yet in use). Rather than watch everyone starve, Clotild leads them on a pilgrimage that culminates in the aforementioned rebellion. Yes, we all know how such a rebellion ends. But Charlier’s fictional account of a forgotten chapter in history makes an inspiring read.

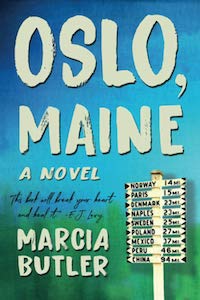

Marcia Butler, Oslo, Maine

(Central Avenue Publishing)

Here at the end of the list is, yes, the novel featuring a pregnant moose. Bear with me, because the moose isn’t necessarily the protagonist of Butler’s latest novel. But she might be its beating heart, because her perspective—which opens the book—is so wild and twitchy and instinctive yet also so universal and beautiful and meaningful. Some readers might remember, from Butler’s amazing memoir The Skin Above My Knee, that she was for many years an accomplished oboist, and it’s from 15 years of experience playing in a Maine chamber festival that she draws on to create her wild and beautiful view of a small town in that state where music works on many people’s instincts in many ways. Please don’t blame me, however, if the sections with the moose make you weep; they aren’t necessarily traumatic, but the author’s deep compassion for a different species means that you will wonder why more writers don’t choose to include all manner of beasts in their narratives.

Bethanne Patrick

Bethanne Patrick is a literary journalist and Literary Hub contributing editor.