Back to School For Everyone: Hybrid Poetry with Ocean Vuong

Its Tradition, Innovations, and Radical Possibilities

“Prose is a house, poetry a man in flames running quite fast through it.”

–Anne Carson

*Article continues after advertisement

Although this class focuses on how poets hybridize their work, moving from the lyric to more prosaic, non-rhythmic modes, it’s necessary to begin by attempting to define the novel and its relation to the genres that preceded it. This, of course, is a trick question in so far as whether the novel can be defined at all—or perhaps defined only in its negation.

Since it had to wait until the other forms (the epic and lyric poems, the romance, chronicle, drama, and historiography) matured, not to mention the arrival of the printing press, the novel as a young “genre” is not so much a genre at all so much as an organizing principle, one that’s malleable, elusive, and also one which enacts as well as contains. I like to call it, anachronistically, a queer container since its functions are meant to shift, alter, revise, but also be capacious enough to fold the older genres into it: a container made of water.

This is evident in our species’ very first novel, The Tale of Genji. Written by Lady Murasaki Shikibu in 1011, over half a millennia before Cervantes’ Don Quixote, the Japanese book anticipated European modernist techniques including syntactical fragmentation, dream sequences, non-linear temporal plotting, character interiority, and an unreliable, imperfect narrator. When Shikibu, a lady in waiting, was asked why she would venture to write such an epic work, she claimed that she wrote it merely out of boredom.

It was not until the 18th- and 19th-century English realist novel had come to prominence, in what some now call the “golden age” of fiction, that fiction’s characteristic as a genre came to hegemonic influence. Even contemporary critics, either consciously or not, will measure a new novel against the standards that arose out of this brief epoch, favoring Victorian ideals like cohesion, character “improvement” or change, appropriately timed climactic sequencing, and plot twists that culminate toward a grand denouement, thereby delivering on the phallic promise of a release enacted as closure with “substance.”

Through globalized discourse and Eurocentric literary pedagogy as a gold standard, even among elite institutions outside of the West, these trademarks, originally local to Europe, have now prevailed to near universal acceptance, all but erasing the myriad and variegated fiction traditions enacted across the globe. This seminar, then, takes a look at how poets resist this arbitrary genre hegemony in their respective milieus in order to breach its legitimacy from the 19th-century onward (save for Basho), when genre definitions begin to have more influence on a burgeoning commercialized literary culture.

In other words, although the novel has no truly fixed rubrics, this class focuses on how writers, interested in troubling their epoch’s genre expectations, composed their texts via a subversive and oppositional dialectic that dissolves genre borders toward “hybridity.” More so, we get to see how and why these poets have decided, despite investing so much time in it, that the lyric would no longer suffice their aspirations. What happens, then, when the lyric is not enough? When social and national crises become catalysts for ontological disintegration? This class doesn’t purport to answer all these questions, but at our best, we might widen the theater of curiosity in which a rich and lively discourse might be realized.

Course description

In this class, we will examine possibilities in textual and formal hybridity, paying close attention to how this nascent yet rich lineage of writing blurs, disrupts, and alters the boundaries of genres as it relates to auto-biographical interrogations in literature. What happens when a piece of writing challenges the preconceived parameters of its genre, rendering itself elusive, amorphous, and yet still insisting on its value as a means of intellectual and emotional discovery? What use are genre labels, and can these terms be modified alongside the development of inter-genre writing? How does a writer’s own “hybridity” in identity relate to her intersection in formal enactments?

We will read both the trailblazers and newcomers to the form, as well as try our own hand at creating a hybrid text that surprises, challenges, and confronts our own notions of what fiction, poetry, and the essay should or should not be, and how those notions can change. The goal, in the end, is to expand and enlarge our sense of self and the potentialities within our craft through careful reading, compositional imitation, and rigorous discussion.

Reading list

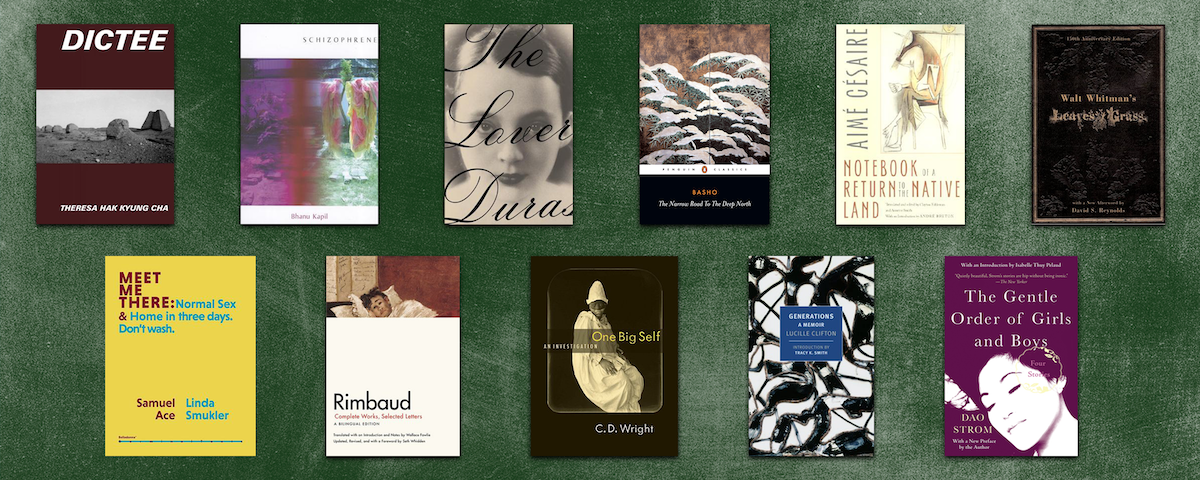

Theresa Hak Kyung Cha, Dictee • Bhanu Kapil, Schizophrene • Marguerite Duras, The Lover • Matsuo Bashō, The Narrow Road to the Deep North and Other Travel Sketches • Aimé Césaire, Notebook of a Return to the Native Land • Walt Whitman, Leaves of Grass • Samuel Ace/ Linda Smukler, Meet Me There • Arthur Rimbaud, Arthur Rimbaud: Complete Works Bilingual Edition • C.D. Wright, One Big Self • Lucille Clifton, Generations • Dao Strom, The Gentle Order of Girls and Boys

Ocean Vuong

Ocean Vuong is the author of the New York Times bestselling poetry collection Time is a Mother (Penguin Press 2022), and the New York Times bestselling novel On Earth We're Briefly Gorgeous (Penguin Press 2019), which has been translated into 37 languages. A recipient of a 2019 MacArthur "Genius" Grant, he is also the author of the critically acclaimed poetry collection Night Sky with Exit Wounds, a New York Times Top 10 Book of 2016, winner of the T.S. Eliot Prize, the Whiting Award, the Thom Gunn Award, and the Forward Prize for Best First Collection. Born in Saigon, Vietnam, he currently lives in Northampton, Massachusetts and serves as a tenured Professor in the Creative Writing MFA Program at NYU.