Aymann Ismail on Asking the Right Questions (at the Right Time)

“Memoirs ought to interrogate certainties.”

This first appeared in Lit Hub’s Craft of Writing newsletter—sign up here.

Long before I was a writer, I was a photographer and video journalist at ANIMAL New York, a scrappy graffiti and art magazine where my job was to document cool people doing cool things, usually in studios, but more often in alleys or dusty subway tunnels. The staff was tiny. One day, right around the anniversary of 9/11, Marina Galperina, our in-house writer/editor genius, asked if I had a story because, you know, I’m Muslim. I wasn’t sure there was much to tell. My memories felt typical for kids my age. There was ambient fear, the sudden flag-waving at the mosque to prove loyalty, the FBI knocking on our Newark door looking for a “Mohamed Mohamed,” which is basically like a John Doe who eats falafel.

I sat with Marina and spilled everything. She transcribed it, trimmed the fat, handed it back, and said, “Look good?” I was taken aback. She presented it like it was a piece I’d written. She told me they were all my words. “It’s your story,” she told me when I tried to refuse the byline. That’s how I accidentally wrote my first article for the magazine.

Over a decade later, and I’m now a staff writer at Slate, and the process is still hilariously similar. I come up with ten to fifteen questions that are embarrassingly simple, questions I truly do not know the answer to. (Skip the noble thesis questions. They’re performative and you get back performative answers.)

When I wrote my memoir, Becoming Baba, I took a cue from Marina and hit record to interview myself: “What did I expect fatherhood to be like?” “What will I teach my kids about being Muslim in America?” I did the same with my parents (who, as you’ll see in the book, can make discussions feel like a heist), asking, “What do you remember from Egypt?” and “What regrets do you have about raising us here?” My palms sweated asking the shamey ones. That usually means I’m on the right track.

Trust the audience. Let them work. I did my best to plant clues so readers could connect the constellations themselves.

My best confessions came while driving, phone on the dashboard. With family, I call instead of sitting across from them. A visible recording phone makes can make some people too nervous to be honest. I learned that with my family, making them feel like I’m asking for help, not harvesting trauma, was the secret sauce. I cap sessions around forty-five minutes. Trust me, there is such a thing as too much tape. If the vibe gets wooden, I lob a grenade: “That’s not how I remember it.” Nothing animates Egyptian parents faster than a child correcting them.

Once it’s transcribed, first pass is for tempo. Cut the drag. Second is for color. Add in smell, taste, movement. Third is for meaning. The scene reveals what it’s actually about: Quran, food, sibling rivalry, a bottle of breast milk spilled on kitchen floor. By then I’m not writing so much as DJ’ing, just blending tracks until the beat makes sense.

Because my book is about people, I got really nervous that they’d read themselves like cardboard cutouts, just existing for things to happen to them. So I tried to treat every person like a small universe with its own gravity. They want things, fear things, eat oranges and either toss the peel in the trash or let it fossilize on the counter. My editor, Thomas Gebremedhin, repeated to me at every stage of writing “show, don’t tell.” Trust the audience. Let them work. I did my best to plant clues so readers could connect the constellations themselves.

And if you’ve got kids (hi, guilty), the “Play with me!” tug mid-paragraph is not sabotage; it’s a blessing. Go play. You can get back to writing again after bedtime. They will never be this small again. I’ve walked away mid-sentence to build a block tower and come back two hours later with a sharper sense of story.

Now, for the secret weapon. Your worst critic. The least charitable reader imaginable. The troll. I keep that person in the room, not to appease them, but to mine their suspicion for blind spots. Call it my anti-muse. “What will they pounce on here? What’s the lazy assumption they’ll make about me, my faith, my family?” When I feel like I’ve finished, I let that voice heckle. When I wrote about my marriage, that voice went: “Doesn’t this guy’s ‘Kore-annn’ tell him to hate women?” That sneer I’ve heard in real life before, and it jogged a memory: me opening the Quran with Mira, asking what a Muslim marriage actually looks like. Suddenly I felt like I had a scene with stakes. Thanks for your help, racists!

My best writing happens when I use bad faith readings as a metal detector for the buried questions I’m afraid to ask. Memoirs ought to interrogate certainties. Thinking of the troll perspective can help you write out the part they’d try to flatten. They’ve pointed me toward the things I avoid because I didn’t have the language yet. They’ve reminded me to clarify a fact before someone has the chance to “well, actually” in their head. Their presence kept me nimble and interesting. In Becoming Baba, I thought of them as a character too, with motives and fears, whose imagined objections nudged me into the deeper truths that make the book interesting.

If you’re looking for inspo, of course I’m going to tell you to read Becoming Baba. But also pick up Hala Alyan’s I’ll Tell You When I’m Home, Amanda Hess’s Second Life, and Ta-Nehisi Coates’s Between the World and Me. Master classes in asking brave questions. Then open your voice memo app, name it something unhinged like “Voice Recording — Dark Thoughts 3” and press record. If what you reveal scares you, that means it’s working.

___________________________________

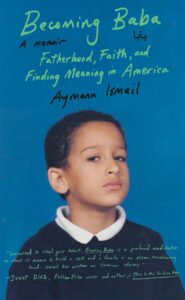

Becoming Baba: Fatherhood, Faith, and Finding Meaning in America by Aymann Ismail is available via Doubleday.

Aymann Ismail

Aymann Ismail is an award-winning Slate magazine staff writer whose journalism focuses on identity and religion. He is the creator of the Slate video series “Who’s Afraid of Aymann Ismail?,” in which he offers an intimate portrayal of American Muslims. Ismail also hosts “Man Up”–a podcast exploring men, relationships, family, race, and sex–which seeks to provide a blueprint for navigating discussions of masculinity. In addition to Slate, his work has been featured on CNN, The New York Times, NPR, GQ, The Atlantic, Columbia Journalism Review, and The Huffington Post. Ismail’s writing has been nominated for the National Magazine Award in reporting and he has won a Writers Guild Award. He lives in Newark, New Jersey with his family.