While they slept, the sun lifted itself above the mountain surround to spread light on the little city below. Inside that city, urban deer glided across frozen November lawns to return to their hollows under backyard pines. Feline huntresses licked the blood off their paws and went home for kibbles and stomach rubs. A tied-up, shivering dog made three tight circles in the dirt and began to bark. Two joggers with lights on their shoes panted grimly and stepped up their pace. An old Falcon moved slowly, ejecting rolled newspaper onto front steps. And then a roseate calm prevailed, and the mountains moved in closer.

While they slept, in their boxes inside the bigger box of their four-story building, street sounds began: the buses, the early workers. The river moved with low-water deliberation through the center of town, carrying oblong shards of ice beneath one bridge and then another. A muttering man with crazy hair dragged a lumpy sleeping bag from a stand of tall bushes and resettled himself beneath the second bridge, up under the trusses, a few yards from the coffee place on the ground floor of the new bank.

They slept not far from the river in a neighborhood thickly planted with maples and tall old homes, in a twenty-four-unit residence for senior called Pheasant Run.

In a normal autumn, the maples put on showy displays, fanning high into the sky, then shattering into slow red waterfalls until the branches were lattices, not crowns, and the sky was twice as large. This year, the leaves have refused to drop. They have clung, ash-colored, to the branches, inspiring general unease and several letters to the newspaper, which invited a certified arborist to weigh in. He explained that the normal separation process between leaf and twig produces a membrane that seals off the leaf and enables it to fall. Extreme cold at the wrong time, like the shocking, subzero stretch of days that happened in October, can derail that process, he said. The tree “basically clutches,” and the leaves stay attached. They were strange those gray leaves, abiding in the wrong place at the wrong time. They turned the trees to sepia-toned photographs, or remembered trees, or witnesses to some sapless aftermath.

While they slept, the sun lifted itself above the mountain surround to spread light on the little city below.

They slept at Pheasant Run, and then they woke and prepared to move into a day with nothing, yet, about it to suggest the small and large shocks to come.

Faint, predictable smells trickled into the hallways: oatmeal, burned toast. Some televisions were turned on for talk shows or weather, and a few were loud enough, because of their owners’ hearing difficulties, that the adjacent tenants began another day feeling cranky and contemplating notes of complaint.

The morning noises tended not to include conversation, as most of the residents lived alone or with an ailing, late-sleeping spouse.

*

At six-thirty, Cassie McMackin in #412, an early rise by habit, drank her coffee and counted the pills she had accumulated during her late husband’s long decline. There were relaxants that had unsuccessfully addressed his night roaming, plus several versions of painkillers, prescribed after two falls and some broken ribs, and so dizzy-making for Neil that he started giving them wary, sidelong looks whenever she urged one on him, and it soon became clear that nothing was better than something.

Now she had a couple of fistfuls in the narcotic and soporific categories, and this evening she would take them all, with antinausea medication and as much wine as she could get down. It was time. She had become tired of the world. Her blood didn’t want to go anywhere anymore, and it had not been for the instructions of her bossy and indefatigable heart, it wouldn’t. She didn’t want to occupy some interminable waiting room where nothing was wrong and nothing was right, her motions mechanical, eyes on the tyrant clock. It was time.

At eighty-seven, she was fine-boned and straight-backed, and she tended to wear interesting clothes, like the silk robe she’d thrown on over her nightgown, a shimmering gold-toned garment with bat-wing sleeves. Her silver hair framed her face in a short pageboy. The red lipstick and frank black eyebrows of her earlier days had muted to softer shades, but it was a face that echoed unusual beauty, still.

Right this moment, what she missed was the prospect of a second cup of coffee with her friend, John Quant, who had moved, a year ago, into an apartment on the third floor of the building, directly beneath her own. Soon after they met, they had progressed from polite greetings to longer conversations, to morning coffee, to dinner in Cassie’s apartment every week or so, with candles and maybe a TV movie with dessert. She had felt in his company as if she was emerging from years of emotional and physical hibernation. Her happiness shocked her.

At six thirty, Cassie McMackin in #412, an early rise by habit, drank her coffee and counted the pills she had accumulated during her late husband’s long decline.

She liked his looks—tall and sharp-shouldered, his eyes an inquiring blue—and she liked his wit, his laughter, and his combination of irreverence and courtliness. Eventually, she had felt between them a tacit acknowledgment of an alliance that could only be called romantic, in the sense that it fawned outward into whatever futures they would be granted, and it shimmered with excitement in that space.

And then, four weeks ago, there had been a sharp knock on her door, and he told her he was moving back to the little town up north where he had been a boy. For the first time since she’d known him he seemed evasive; he said only that Pheasant Run was not a good fit for him anymore, that he didn’t like the feel of the place, and he particularly didn’t like the new on-site manager, Herbie Bonebright. He told her he didn’t feel he had a choice. He wouldn’t look at her straight on. He had closed and locked the door to himself.

And he was gone, in a blink. She’d heard not another word from him, and knew she wouldn’t. All she could do was add him to her list of those who’d left. John Quant, and before him her only child. And her husband of six decades. They’d flown away, leaving her craning her head skyward, aghast, as they became pinpricks and disappeared. She couldn’t fully believe it, still. The flights. This final aloneness.

__________________________________

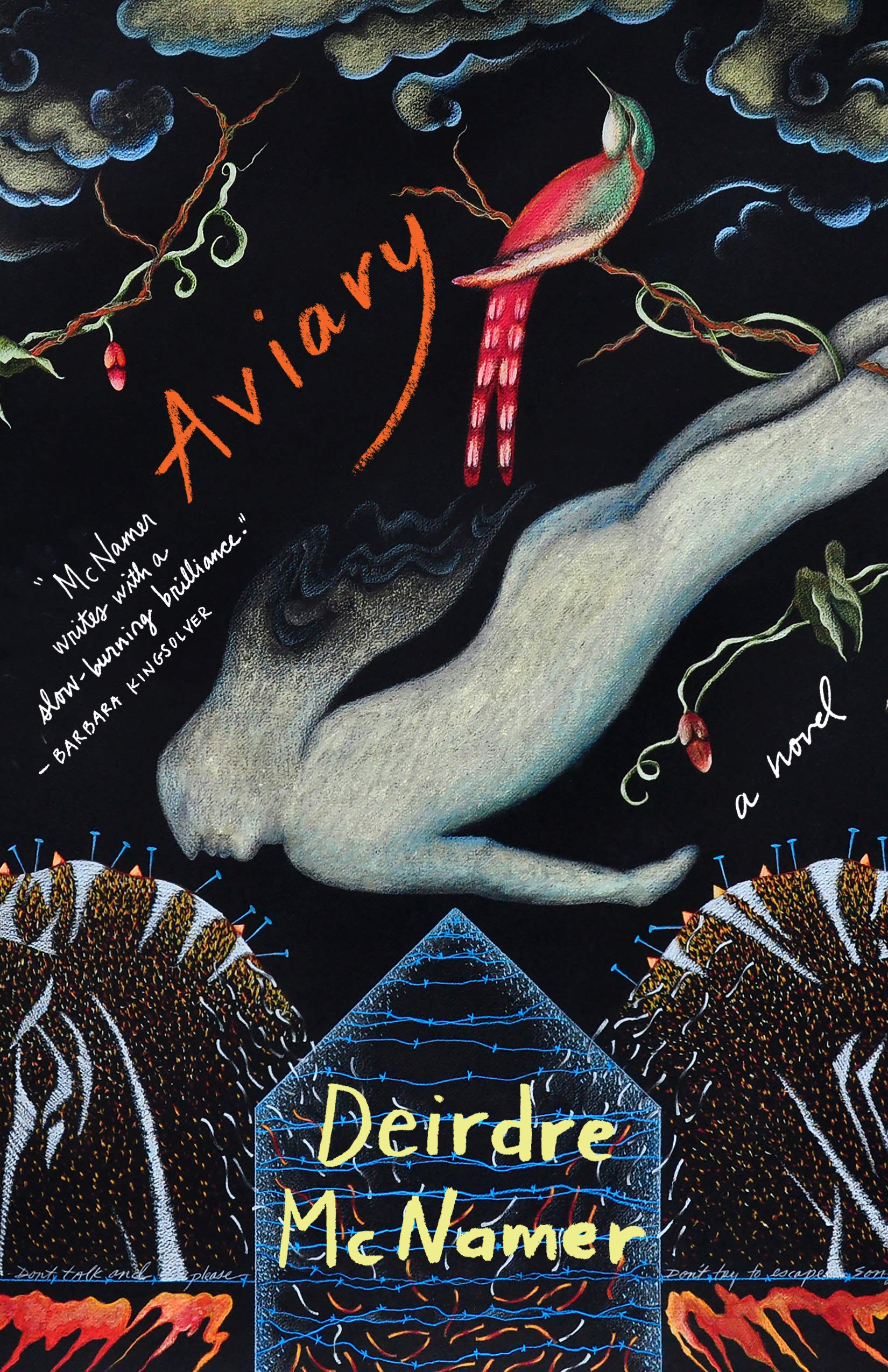

Excerpted from Aviary by Deirdre McNamer. Excerpted with the permission of Milkweed. Copyright © 2021 by Deirdre McNamer.