[A wild wind; wind from the north]

The sound of hooves beating on the sandy ground comes first. Then the breathing, strained and short-winded. Panting. A snort. The white ground splits to allow the emergence of twisted acacias, with their rounded crowns and roots embedded deeply in the earth, and the thorny branches of mesquites, from which hang long, narrow pods and, now that it’s almost spring, these yellow flowers. The galloping doesn’t stop. Horseshoes dodge the spherical barrel cacti, whose burnished spiny tips appear here and there along the road. The white flowers of the anacahuita. The roadrunners. The worm lizards. Hadn’t he been told this was a desert? There’s no time to stop and look. From above, the light of an intransigent sun falls on the creosote bush, the coyotillo, the cat’s claw. And the wind, raising the pinkish, gray, and cinnamon-colored dust of the plain, collides with the prickly pads of the nopal that ascend step by step, toward the sky. The earth crumbles as he passes, and everything around him thirsts for water. His mouth, most of all. His larynx. His stomach. He’s not sure how many hours he’s been mounted on the horse—thighs around the reddish torso, shoulders slumped forward, hands clenching the reins, and shoes crammed into the stirrups—but he’d like to feel he was nearing his destination. He’s been told that there—a day’s ride if he manages to get a change of horse—is where things are really happening. He’s been told that if he wants to see direct action, if he truly wants to change the world, he should head farther north. There, just a stone’s throw from the border, is Estación Camarón.

A strike has just broken out there.

[Gossypium hirsutum]

They are called “stations” because they are transit points, but just as soon as they are erected, people begin to move in. They are rancherias, colonias, settlements that never reach city status but that spring up in the blink of an eye around a crossroads. First comes the railroad; then, a camp. Later, somewhere to eat. From insignificant points on the map of a steppe with a reputation for being uninhabitable or a desert everyone steers clear of, they become places with names: Estación Rodríguez, for the rancher’s name; Estación Camarón, for the reddish tint left by the waters of a river. Things are born and die several times in unpredictable cycles. One fine day, a general who has won the war looks out to the horizon and, instead of seeing a grim, dry wilderness, instead of seeing inhospitable prairies or empty spaces, sees neatly ordered parcels of land, sees crops and harvests. And he thinks: The agriculture will start here. His declaration would sound less grandiose if it weren’t true. In brief memoranda, he orders the construction of a dam at the confluence of two rivers. And that dam also acquires a name: the Don Martín. Then it’s a matter of allotting land. Correction: It’s a matter of expropriating and then allotting land. And so, after decades of lying abandoned, the area was slowly repopulated. After years without a mail service, without telegrams, without a single face peeking through the dirty windows of the railroad carriages, heaps of people are there again. Men and women from Nuevo León and Coahuila, from San Luis Potosí and Texas, from Arizona, California, and heaven knows where else. Men, women, and children. Entire families loaded onto those wagons they call guayins, pulled by a pair of aged mules, plodding slowly and steadily along dirt tracks. Families on foot. People who stop to hunt an animal to have something to put in their bellies: a hare, some species of vesper rat, and, with a little luck, a wild boar. People who light fires to boil water and ward off the coyotes, and who rub their hands together as they stare into the flames. The echo of conversations. Laughter. After so much hardship, hope springs again. Behind him, to the south, is the municipality of Lampazos and gradually, on his focused gallop forward, scattered shacks and lanes, adobe houses, and domestic animals begin to appear. A creek. To the east lies that same bald plain with the occasional white-tailed deer and rabbit. On the other side is the municipality of Juárez, pitted with the pools and sinkholes of coal mining. The Barroterán mines. Rosita. Palaú. Cloete. Las Esperanzas. All those pitheads, the mouths of which swallow men whole every morning. And farther off, toward the mountains, the Cimarronaje—the settlements of the Black Seminoles and Mascogos who, on escaping slavery, became colonists of a territory that asked for their protection in exchange for ownership. But now, not east, west, or south. It only makes sense to continue north, farther north, until he merges into the border.

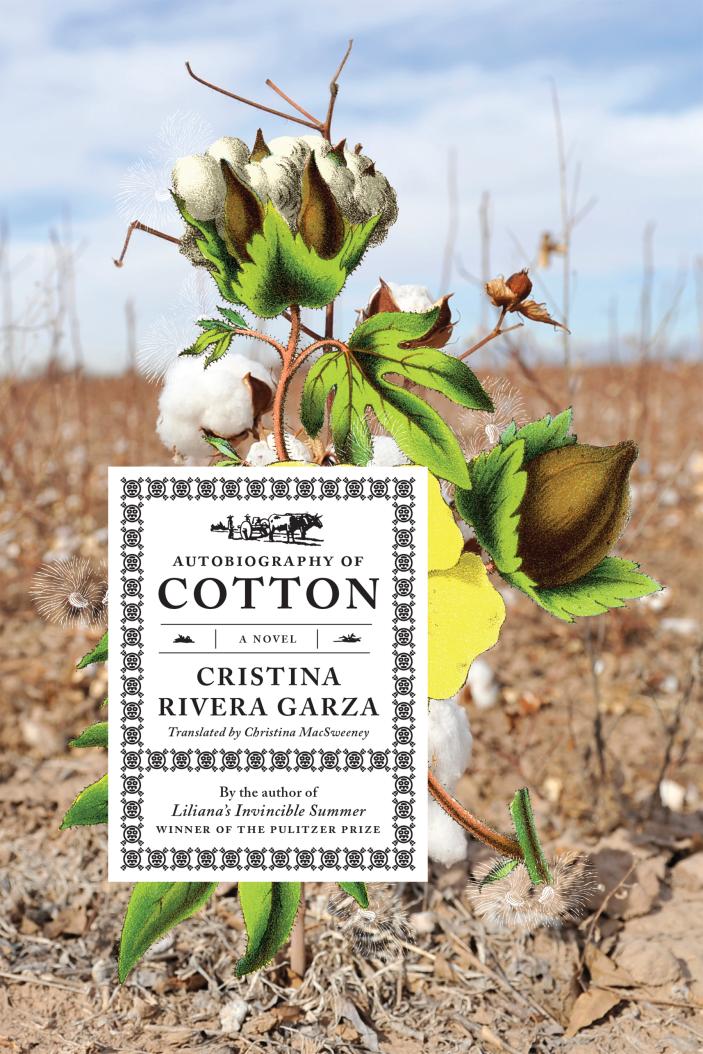

He could stop for a while, but desire is a cruel master. He could slow down, pay more attention to the people walking or chatting in languages he half hears and half understands. But he knows that if he catches sight of the railroad bridge that means he’s just passed Estación Rodríguez, and he needs to cross the Río Salado, now such a meager trickle, it could be taken for a creek. He could also stop here to drink or wet the handkerchief someone had advised him to tie around the back of his neck, but he’s very close now. He could at least pause to stretch his legs and see if that did anything to relieve the pain in his thighs, rising to numb his butt, and up to his hips, but he keeps going. Skin burning. Bone-breaking. He could at least allow the horse carrying him across the scrubland to drink water, but better to dig in the stirrups to spur it on. Something is urging him on. He’s been told that after Estación Rodriguéz, on the other side of the river, is the settlement of Anáhuac. And there he’ll find the banks, the suppliers, the government offices, the theaters, and cantinas. But better just to continue along the wide streets around the circular plaza, a kilometer in diameter. Better just to glimpse, out of the corner of his eye, the obelisk with its modernist air rising up in the center of the plaza and only get a fleeting, distant view of the wind rose at its base. The four cardinal points of space; the three stations of time. When the streets and the plaza and the concrete benches are behind him, when the theaters, the cantinas, and streetlights have passed, he knows he’s nearly there. Desire, which has been his guide during the hours of riding on horseback across the plains, leaves him no peace. Desire fires him, cuts him to pieces, lambastes him. Desire opens up his imagination and closes down his fear. But the desire that has opened his eyes and kept him alert hasn’t prepared him for this. When he reaches the cotton fields on either side of the road, he rubs those eyes. So, this is the white gold, he says to himself. He hasn’t even realized that he has come to a dead halt. The horse, not sensing any guidance on its ribcage, begins to move skittishly in tight, concentric circles. José? They have to repeat his name a couple of times before he finally tears his gaze from the cotton plantation and can answer. José, Pepe? The smile says yes, it’s him. His nod says yes, it’s him. The leap from his mount onto the whitish ground says yes, it is him.

__________________________________

From Autobiography of Cotton by Cristina Rivera Garza, translated by Christina MacSweeney). Used with permission of the publisher, Graywolf Press. Copyright © 2026.