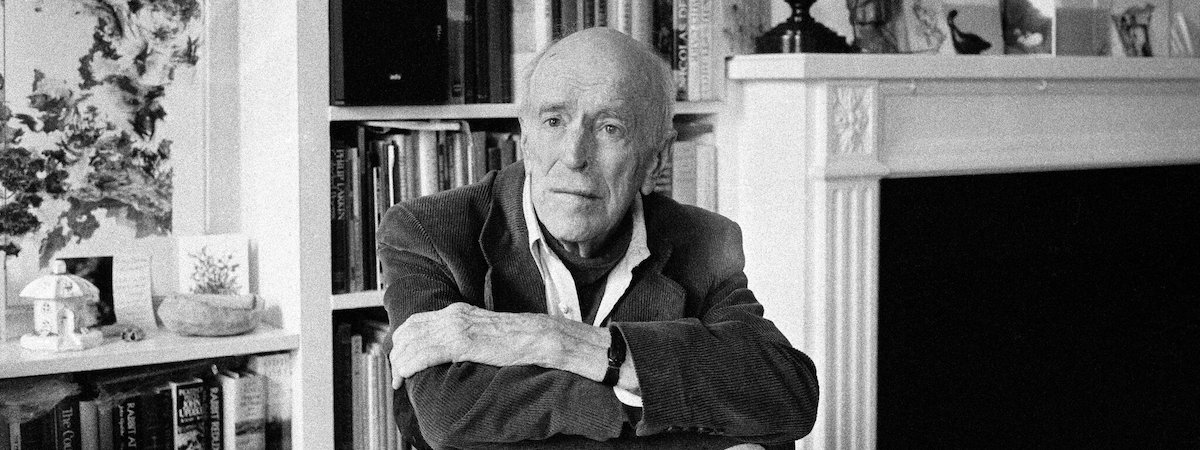

Author as Illusionist: William Maxwell on Literary Magic and Refusing to Give Up as a Writer

Alec Wilkinson Introduces Maxwell’s Speech at Smith College in 1955

This speech was written during a period when William Maxwell was discouraged over what he felt was a lack of public encouragement and he had thought that he might give up writing and just be an editor. In a journal he wrote,

I do not ever want to write again. I want checks to come in and requests for reprint and translation rights from every country under the sun….

The two subjects I have are both highly introspective and lacking in action—the man without confidence, the man who doubts his capacity to love. They are probably the same subject….

Who will I take as a model, as a clue to subject matter. Not Flaubert, because I don’t want it to be cold. Not Conrad, because it has to be not adventurous. The hero must be forty, and not trail along behind me. Wells, Joyce, Dostoievsky? It should have an action, and not begin with a character or a psychological difficulty….

The speech consists of notes that Maxwell had been keeping for a piece of writing and a companion text that he wrote almost entirely on the train to Massachusetts. The section of instructions—”Begin with the…”—are the part that was written beforehand. By the time the train had arrived, he had finished the speech and decided that he liked writing too much to give up.

–Alec Wilkinson

*

A speech delivered at Smith College on March 4, 1955.

One of the standard themes of Chinese painting is the spring festival on the river. I’m sure many of you have seen some version of it. There is one in the Metropolitan Museum. It has three themes woven together: the river, which comes down from the upper right, and the road along the river, and the people on the riverbanks.

As the scroll unwinds, there is, first, the early-morning mist on the rice fields and some boys who cannot go to the May Day festival because they have to watch their goats. Then there is a country house, and several people starting out for the city, and a farmer letting water into a field by means of a water wheel, and then more people and buildings—all kinds of people all going toward the city for the festival. And along the riverbank there are various entertainers—a magician, a female tightrope walker, several fortune-tellers, a phrenologist, a man selling spirit money, a man selling patent medicine, a storyteller.

I prefer to think that it is with this group—the shoddy entertainers earning their living by the riverbank on May Day—that Mr. Bellow, Mr. Gill, Miss Chase, on the platform, Mr. Ralph Ellison and Mrs. Kazin, in the audience, and I, properly speaking, belong. Writers—narrative writers—are people who perform tricks.

Before I came up here, I took various books down from the shelf and picked out some examples of the kind of thing I mean. Here is one:

“I have just returned this morning from a visit to my landlord—the solitary neighbor that I shall be troubled with….”

Writers—narrative writers—are people who perform tricks.

One of two things—there will be more neighbors turning up than the narrator expects, or else he will very much wish that they had. And the reader is caught; he cannot go away until he finds out which of his two guesses is correct. This is, of course, a trick.

Here is another: “None of them knew the color of the sky….” Why not? Because they are at sea, pulling at the oars in an open boat; and so are you.

Here is another trick: “Call me Ishmael….” A pair of eyes looking into your eyes. A face. A voice. You have entered into a personal relationship with a stranger, who will perhaps make demands on you, extraordinary personal demands; who will perhaps insist that you love him; who perhaps will love you in a way that is upsetting and uncomfortable.

Here is another trick: “Thirty or forty years ago, in one of those gray towns along the Burlington railroad, which are so much grayer today than they were then, there was a house well known from Omaha to Denver for its hospitality and for a certain charm of atmosphere.”

A door opens slowly in front of you, and you cannot see who is opening it but, like a sleepwalker, you have to go in. Another trick: “It was said that a new person had appeared on the seafront—a lady with a dog….”

The narrator appears to be, in some way, underprivileged, socially. She perhaps has an invalid father that she has to take care of, and so she cannot walk along the promenade as often as she would like. Perhaps she is not asked many places. And so she has not actually set eyes on this interesting new person that everyone is talking about. She is therefore all the more interested. And meanwhile, surprisingly, the reader cannot forget the lady, or the dog, or the seafront.

Here is another trick: “It is a truth universally acknowledged that a single man in possession of a good fortune must be in want of a wife….”

An attitude of mind, this time. A way of looking at people that is ironical, shrewd, faintly derisive, and that suggests that every other kind of writing is a trick (this is a special trick, in itself ) and that this book is going to be about life as it really is, not some fabrication of the author’s.

So far as I can see, there is no legitimate sleight of hand involved in practicing the arts of painting, sculpture, and music. They appear to have had their origin in religion, and they are fundamentally serious. In writing—in all writing but especially in narrative writing—you are continually being taken in. The reader, skeptical, experienced, with many demands on his time and many ways of enjoying his leisure, is asked to believe in people he knows don’t exist, to be present at scenes that never occurred, to be amused or moved or instructed just as he would be in real life, only the life exists in somebody else’s imagination.

If, as Mr. T. S. Eliot says, humankind cannot bear very much reality, then that would account for their turning to the charlatans operating along the riverbank—to the fortune-teller, the phrenologist, the man selling spirit money, the storyteller. Or there may be a different explanation; it may be that what humankind cannot bear directly it can bear indirectly, from a safe distance.

The writer has everything in common with the vaudeville magician except this: The writer must be taken in by his own tricks. Otherwise, the audience will begin to yawn and snicker. Having practiced more or less incessantly for five, ten, fifteen, or twenty years, knowing that the trunk has a false bottom and the opera hat a false top, with the white doves in a cage ready to be handed to him from the wings and his clothing full of unusual, deep pockets containing odd playing cards and colored scarves knotted together and not knotted together and the American flag, he must begin by pleasing himself.

His mouth must be the first mouth that drops open in surprise, in wonder, as (presto chango!) this character’s heartache is dragged squirming from his inside coat pocket, and that character’s future has become his past while he was not looking.

With his cuffs turned back, to show that there is no possibility of deception being practiced on the reader, the writer invokes a time: He offers the reader a wheat field on a hot day in July, and a flying machine, and a little boy with his hand in his father’s. He has been brought to the wheat field to see a flying machine go up. They stand, waiting, in a crowd of people. It is a time when you couldn’t be sure, as you can now, that a flying machine would go up.

Hot, tired, and uncomfortable, the little boy wishes they could go home. The wheat field is like an oven. The flying machine does not go up.

The writer will invoke a particular place: With a cardinal and a tourist home and a stretch of green grass and this and that, he will make Richmond, Virginia. He uses words to invoke his version of the Forest of Arden.

If he is a good novelist, you can lean against his trees; they will not give way. If he is a bad novelist, you probably shouldn’t. Ideally, you ought to be able to shake them until an apple falls on your head. (The apple of understanding.)

The novelist has tricks of detail. For example, there is Turgenev’s hunting dog, in A Sportsman’s Notebook. The sportsman, tired after a day’s shooting, has accepted a ride in a peasant’s cart, and is grateful for it. His dog is not. Aware of how foolish he must look as he is being lifted into the cart, the unhappy dog smiles to cover his embarrassment.

There is the shop of the live fish, toward the beginning of Malraux’s Man’s Fate. A conspirator goes late at night to a street of pet shops in Shanghai and knocks on the door of a dealer in live fish. They are both involved in a plot to assassinate someone. The only light in the shop is a candle; the fish are asleep in phosphorescent bowls. As the hour that the assassination will be attempted is mentioned, the water on the surface of the bowls begins to stir feebly. The carp, awakened by the sound of voices, begin to swim round and round, and my hair stands on end.

The writer has everything in common with the vaudeville magician except this: The writer must be taken in by his own tricks. Otherwise, the audience will begin to yawn and snicker.

These tricks of detail are not important; they have nothing to do with the plot or the idea of either piece of writing. They are merely exercises in literary virtuosity, but nevertheless in themselves so wonderful that to overlook them is to miss half the pleasure of the performance.

There is also a more general sleight of hand—tricks that involve the whole work, tricks of construction. Nothing that happens in Elizabeth Bowen’s The House in Paris, none of the characters, is, for me, as interesting as the way in which the whole thing is put together. From that all the best effects, the real beauty of the book, derive.

And finally there are the tricks that involve the projection of human character. In the last book that I have read, Ann Birstein’s novel, The Troublemaker, there is a girl named Rhoda, who would in some places, at certain periods of the world’s history, be considered beautiful, but who is too large to be regarded as beautiful right now. It is time for her to be courted, to be loved—high time, in fact. And she has a suitor, a young man who stops in to see her on his way to the movies alone.

There is also a fatality about the timing of these visits; he always comes just when she has washed her hair. She is presented to the reader with a bath towel around her wet head, her hair in pins, in her kimono, sitting on the couch in the living room, silent, while her parents make conversation with the suitor. All her hopes of appearing to advantage lie shattered on the carpet at her feet. She is inconsolable but dignified, a figure of supportable pathos. In the midst of feeling sorry for her you burst out laughing. The laughter is not unkind.

These forms of prestidigitation, these surprises, may not any of them be what makes a novel great, but unless it has some of them, I do not care whether a novel is great or not; I cannot read it.

It would help if you would give what I am now about to read to you only half your attention. It doesn’t require any more than that, and if you listen only now and then, you will see better what I am driving at.

Begin with breakfast and the tipping problem.

Begin with the stealing of the marmalade dish and the breakfast tray still there.

The marmalade dish, shaped like a shell, is put on the cabin class breakfast tray by mistake, this once. It belongs in first class.

Begin with the gate between first and second class.

Begin with the obliging steward unlocking the gate for them.

The gate, and finding their friends who are traveling first class, on the glassed-in deck.

The gate leads to the stealing of the marmalade dish.

If you begin with the breakfast tray, then—no, begin with the gate and finding their friends.

And their friends’ little boy, who had talked to Bernard Baruch and asked Robert Sherwood for his autograph.

The couple in cabin class have first-class accommodations for the return voyage, which the girl thinks they are going to exchange, and the man secretly hopes they will not be able to.

But they have no proper clothes. They cannot dress for dinner if they do return first class.

Their friend traveling first class on the way over has brought only one evening dress, which she has to wear night after night.

Her husband tried to get cabin-class accommodations and couldn’t.

This is a lie, perhaps.

They can afford the luxury of traveling first class but disapprove of it.

They prefer to live more modestly than they need to.

They refuse to let themselves enjoy, let alone be swept off their feet by, the splendor and space.

But they are pleased that their little boy, aged nine, has struck up a friendship with Bernard Baruch and Robert Sherwood.

They were afraid he would be bored on the voyage.

Also, they themselves would never have dared approach either of these eminent figures, and are amazed that they have begotten a child with courage.

The girl is aware that her husband has a love of luxury and is enjoying the splendor and space they haven’t paid for. On their way back to the barrier, they encounter Ber-

nard Baruch.

His smile comes to rest on them, like the beam from a lighthouse, and then after a few seconds passes on.

They discover that they are not the only ones who have been exploring.

Their table companions have all found the gate.

When the steward unlocked the gate for the man and the girl, he let loose a flood.

The entire cabin class has spread out in both directions, into tourist as well as first class.

Begin with the stealing of the marmalade dish.

The man is ashamed of his conscientiousness but worried about the stewardess.

Will she have to pay for the missing marmalade dish?

How many people? Three English, two Americans cabin class. Three Americans first class.

Then the morning on deck.

The breakfast tray still there, accusing them, before they go up to lunch.

The Orkney Islands in the afternoon.

The movie, which is shown to cabin class in the afternoon, to first class in the evening.

The breakfast tray still in the corridor outside their cabin when they go to join their friends in first class in the bar before dinner.

With her tongue loosened by liquor, the girl confesses her crime.

They go down to the cabin after dinner, and the tray is gone.

In the evening the coast of France, lights, a lighthouse.

The boat as immorality.

The three sets of people.

Begin in the late afternoon with the sighting of the English islands.

Begin with the stealing of the marmalade dish.

No, begin with the gate.

Then the stealing of the marmalade dish.

Then the luncheon table with the discovery that other passengers have been exploring and found the gate between first and second class.

Then the tray accusing them. What do they feel about stealing?

When has the man stolen something he wanted as badly as the girl wanted that marmalade dish for an ashtray?

From his mother’s purse, when he was six years old. The stewardess looks like his mother.

Ergo, he is uneasy.

They call on their friends in first class one more time, to say goodbye, and as they go back to second class, the girl sees, as clearly as if she had been present, that some time during the day her husband has managed to slip away from her and meet the stewardess and pay for the marmalade dish she stole.

And that is why the breakfast tray disappeared.

He will not allow himself, even on shipboard, the splendor and space of an immoral act.

He had to go behind her back and do the proper thing.

A writer struggling—unsuccessfully, as it turned out; the story was never written—to change a pitcher of water into a pitcher of wine.

In The Listener for January 27th, 1955, there is a brief but wonderfully accurate description of a similar attempt carried off successfully:

Yesterday morning I was in despair. You know that bloody book which Dadie and Leonard extort, drop by drop from my breast? Fiction, or some title to that effect. I couldn’t screw a word from me; and at last dropped my head in my hands, dipped my pen in the ink, and wrote these words, as if automatically, on a clean sheet: Orlando, a Biography. No sooner had I done this than my body was flooded with rapture and my brain with ideas. I wrote rapidly till twelve….

It is safe to assume on that wonderful (for us as well as her) morning, the writer took out this word and put in that and paused only long enough to admire the effect; she took on that morning or others like it—the very words out of this character’s mouth in order to give them, unscrupulously, to that character; she annulled marriages and brought dead people back to life when she felt the inconvenience of having to do without them. She cut out the whole last part of the scene she had been working on so happily and feverishly for most of the morning because she saw suddenly that it went past the real effect into something that was just writing.

Though the writer may from time to time entertain paranoiac suspicions about critics and book reviewers, about his publisher, and even about the reading public, the truth is that he has no enemy but interruption.

Just writing is when the novelist’s hand is not quicker than the reader’s eye. She persuaded, she struggled with, she beguiled this or that character that she had made up out of whole cloth (or almost) to speak his mind, to open his heart. Day after day, she wrote till twelve, employing tricks no magician had ever achieved before, and using admirably many that they had, until, after some sixty pages, something quite serious happened.

Orlando changed sex—that is, she exchanged the mind of a man for the mind of a woman; this trick was only partly successful—and what had started out as a novel became a brilliant, slaphappy essay. It would have been a great pity—it would have been a real loss if this particular book had never been written; even so, it is disappointing. I am in no position to say what happened, but it seems probable from the writer’s diary—fortunately, she kept one—that there were too many interruptions; too many friends invited themselves and their husbands and dogs and children for the weekend.

Though the writer may from time to time entertain paranoiac suspicions about critics and book reviewers, about his publisher, and even about the reading public, the truth is that he has no enemy but interruption. The man from Porlock has put an end to more masterpieces than the Turks—was it the Turks?—did when they set fire to the library at Alexandria. Also, odd as it may seem, every writer has a man from Porlock inside him who gladly and gratefully connives to bring about these interruptions.

If the writer’s attention wanders for a second or two, his characters stand and wait politely for it to return to them. If it doesn’t return fairly soon, their feelings are hurt and they refuse to say what is on their minds or in their hearts. They may even turn and go away, without explaining or leaving a farewell note or a forwarding address where they can be reached.

But let us suppose that owing to one happy circumstance and another, including the writer’s wife, he has a good morning; he has been deeply attentive to the performers and the performance. Suppose that—because this is common practice, I believe—he begins by making a few changes here and there, because what is behind him, all the scenes that come before the scene he is now working on, must be perfect, before he can tackle what lies ahead.

(This is the most dangerous of all the tricks in the repertoire, and probably it would be wiser if he omitted it from his performance: it is the illusion of illusions, and all a dream. And tomorrow morning, with a clearer head, making a fresh start, he will change back the changes, with one small insert that makes all the difference.)

But to continue: Since this is very close work, watch-mender’s work, really, this attentiveness, requiring a magnifying glass screwed to his eye and resulting in poor posture, there will probably be, somewhere at the back of his mind, a useful corrective vision, something childlike and simple that represents the task as a whole. He will perhaps see the material of his short story as a pond, into which a stone is tossed, sending out a circular ripple; and then a second stone is tossed into the pond, sending out a second circular ripple that is inside the first and that ultimately overtakes it; and then a third stone; and a fourth; and so on.

Or he will see himself crossing a long level plain, chapter after chapter, toward the mountains on the horizon. If there were no mountains, there would be no novel; but they are still a long way away—those scenes of excitement, of the utmost drama, so strange, so sad, that will write themselves; and meanwhile, all the knowledge, all the art, all the imagination at his command will be needed to cover this day’s march on perfectly level ground.

As a result of too long and too intense concentration, the novelist sooner or later begins to act peculiarly. During the genesis of his book, particularly, he talks to himself in the street; he smiles knowingly at animals and birds; he offers Adam the apple, for Eve, and with a half involuntary movement of his right arm imitates the writhing of the snake that nobody knows about yet. He spends the greater part of the days of his creation in his bathrobe and slippers, unshaven, his hair uncombed, drinking water to clear his brain, and hardly distinguishable from an inmate in an asylum.

Like many such unfortunate people, he has delusions of grandeur. With the cherubim sitting row on row among the constellations, the seraphim in the more expensive seats in the primum mobile, waiting, ready, willing to be astonished, to be taken in, the novelist, still in his bathrobe and slippers, with his cuffs rolled back, says Let there be (after who knows how much practice beforehand)….Let there be (and is just as delighted as the angels and the reader and everybody else when there actually is) Light.

[The writer] spends the greater part of the days of his creation in his bathrobe and slippers, unshaven, his hair uncombed, drinking water to clear his brain, and hardly distinguishable from an inmate in an asylum.

Not always, of course. Sometimes it doesn’t work. But say that it does work. Then there is light, the greater light to rule the daytime of the novel, and the lesser light to rule the night scenes, breakfast and dinner, one day, and the gathering together of now this and now that group of characters to make a lively scene, grass, trees, apple trees in bloom, adequate provision for sea monsters if they turn up in a figure of speech, birds, cattle, and creeping things, and finally and especially man—male and female, Anna and Count Vronsky, Emma and Mr. Knightly.

There is not only all this, there are certain aesthetic effects that haven’t been arrived at accidentally; the universe of the novel is beautiful, if it is beautiful, by virtue of the novelist’s intention that it should be.

Say that the performance is successful; say that he has reached the place where an old, old woman, who was once strong and active and handsome, grows frail and weak, grows smaller and smaller, grows partly senile, and toward the end cannot get up out of bed and even refuses to go on feeding herself, and finally, well cared for, still in her own house with her own things around her, dies, and on a cold day in January the funeral service is read over her casket, and she is buried….Then what? Well, perhaps the relatives, returning to the old home after the funeral, or going to the lawyer’s office, for the reading of the will.

In dying, the old woman took something with her, and therefore the performance has, temporarily at least, come to a standstill. Partly out of fatigue, perhaps, partly out of uncertainty about what happens next, the novelist suddenly finds it impossible to believe in the illusions that have so completely held his attention up till now. Suddenly it won’t do. It might work out for some other novel but not this one.

Defeated for the moment, unarmed, restless, he goes outdoors in his bathrobe, discovers that the morning is more beautiful than he had any idea—full spring, with the real apple trees just coming into bloom, and the sky the color of the blue that you find in the sky of the West Indies, and the neighbors’ dogs enjoying themselves, and the neighbor’s little boy having to be fished out of the brook, and the grass needing cutting—he goes outside thinking that a brief turn in the shrubbery will clear his mind and set him off on a new track.

But it doesn’t. He comes in poorer than before, and ready to give not only this morning’s work but the whole thing up as a bad job, ill advised, too slight. The book that was going to live, to be read after he is dead and gone, will not even be written, let alone published. It was an illusion.

So it was. So it is. But fortunately we don’t need to go into all that because, just as he was about to give up and go put his trousers on, he has thought of something. He has had another idea. It might even be more accurate to say another idea has him. Something so simple and brief that you might hear it from the person sitting next to you on a train; something that would take a paragraph to tell in a letter….Where is her diamond ring? What has happened to her furs?

Mistrust and suspicion are followed by brutal disclosures. The disclosure of who kept after her until she changed her will and then who, finding out about this, got her to make a new will, eight months before she died.

The letters back and forth between the relatives hint at undisclosed revelations, at things that cannot be put in a letter. But if they cannot be put in a letter, how else can they be disclosed safely? Not at all, perhaps. Perhaps they can never be disclosed. There is no reason to suspect the old woman’s housekeeper. On the other hand, if it was not a member of the family who walked off with certain unspecified things without waiting to find out which of the rightful heirs wanted what, surely it could have been put in a letter.

Unless, of course, the novelist does not yet know the answer himself. Eventually, of course, he is going to have to let the cat—this cat and all sorts of other cats—out of the bag. If he does not know, at this point, it means that a blessing has descended on him, and the characters have taken things in their own hands. From now on, he is out of it, a recorder simply of what happens, whose business is with the innocent as well as with the guilty. There are other pressures than greed. Jealousy alone can turn one sister against the other, and both against the man who is universally loved and admired, and who used, when they were little girls, to walk up and down with one of them on each of his size-12 shoes.

Things that everybody knows but nobody has ever come right out and said will be said now. Ancient grievances will be aired. Everybody’s character, including that of the dead woman, is going to suffer damage from too much handling. The terrible damaging facts of that earlier will must all come out. The family, as a family, is done for, done to death by what turns out in the end to be a surprisingly little amount of money, considering how much love was sacrificed to it.

And their loss, if the novelist really is a novelist, will be our gain.

For it turns out that this old woman—eighty-three she was, with a bad heart, dreadful blood pressure, a caricature of herself, alone and lonely—knew what would happen and didn’t care; didn’t try to stop it; saw that it had begun under her nose while she was still conscious; saw that she was the victim of the doctor who kept her alive long after her will to live had gone; saw the threads of will, of consciousness, slip through her fingers; let them go; gathered them in again; left instructions that she knew would not be followed; tried to make provisions when it was all but too late; and then delayed some more, while she remembered, in snatches, old deprivations, an unwise early marriage, the absence of children; and slept; and woke to remember more—this old woman, who woke on her last day cheerful, fully conscious, ready for whatever came (it turned out to be her sponge bath)—who was somehow a symbol (though this is better left unsaid), an example, an instance, a proof of something, and whose last words were—But I mustn’t spoil the story for you.

At twelve o’clock, the novelist, looking green from fatigue (also from not having shaved), emerges from his narrative dream at last with something in his hand he wants somebody to listen to. His wife will have to stop what she is doing and think of a card, any card; or be sawed in half again and again until the act is letter-perfect. She alone knows when he is, and when he is not, writing like himself. This is an illusion, sustained by love, and this she also knows but keeps to herself.

It would only upset him if he were told. If he has no wife, he may even go to bed that night without ever having shaved, brushed his teeth, or put his trousers on. And if he is invited out, he will destroy the dinner party by getting up and putting on his hat and coat at quarter of ten, causing the other guests to signal to one another, and the hostess to make a mental note never to ask him again. In any case, literary prestidigitation is tiring and requires lots of sleep.

And when the writer is in bed with the light out, he tosses. Far from dropping off to sleep and trusting to the fact that he did get home and into bed by ten o’clock after all, he thinks of something, and the light beside his bed goes on long enough for him to write down five words that may or may not mean a great deal to him in the morning. The light may go on and off several times before his steady breathing indicates that he is asleep.

And while he is asleep he may dream—he may dream that he had a dream in which the whole meaning of what he is trying to do in the novel is brilliantly revealed to him. Just so the dog asleep on the hearthrug dreams; you can see, by the faint jerking movement of his four legs, that he is after a rabbit.

The novelist’s rabbit is the truth—about life, about human character, about himself and therefore by extension, it is to be hoped, about other people. He is convinced that this is all knowable, can be described, can be recorded, by a person sufficiently dedicated to describing and recording, can be caught in a net of narration.

Why does he bother to make up stories and novels? If you ask him, you will probably get any number of answers, none of them straightforward. You might as well ask a sailor why it is that he has chosen to spend his life at sea.

He is encouraged by the example of other writers—Turgenev, say, with his particular trick of spreading out his arms like a great bird and taking off, leaving the earth and soaring high above the final scenes; or D. H. Lawrence, with his marvelous ability to make people who are only words on a page actually reach out with their hands and love one another; or Virginia Woolf, with her delight in fireworks, in a pig’s skull with a scarf wrapped around it; or E. M. Forster, with his fastidious preference for what a good many very nice people wish were not so.

But what, seriously, was accomplished by these writers or can the abstract dummy novelist I have been describing hope to accomplish? Not life, of course; not the real thing; not children and roses; but only a facsimile that is called literature. To achieve this facsimile the writer has, more or less, to renounce his birthright to reality, and few people have a better idea of what it is—of its rewards and satisfactions, or of what to do with a whole long day.

What’s in it for him? The hope of immortality? The chances are not good enough to interest a sensible person. Money? Well, money is not money any more. Fame? For the young, who are in danger always of being ignored, of being overlooked at the party, perhaps, but no one over the age of forty who is in his right mind would want to be famous. It would interfere with his work, with his family life.

Why then should the successful manipulation of illusions be everything to a writer? Why does he bother to make up stories and novels? If you ask him, you will probably get any number of answers, none of them straightforward. You might as well ask a sailor why it is that he has chosen to spend his life at sea.

______________________________

Excerpted from The Writer as Illusionist: Uncollected & Unpublished Work by William Maxwell. Copyright © 1955 by William Maxwell. Introduction Copyright © 2024 by Alec Wilkinson. Excerpted with the permission of Godine.

William Maxwell

William Maxwell was an American editor, novelist, short story writer, essayist, children’s author, and memoirist. He served as a fiction editor at The New Yorker from 1936 to 1975.