Beauvoir had a kind of genius for being amazed by the world and by herself; all her life she remained a virtuoso marveller at things. As she said in her memoirs, this was the origin of fiction-writing: it began at those times when ‘reality should no longer be taken for granted’.

Sartre envied her this quality. He tried to work himself up into the same state, looking at a table and repeating, ‘It’s a table, it’s a table’ until, he said, ‘a shy thrill appeared that I’d christen joy’. But he had to force himself. It did not wash over him as it did Beauvoir. Sartre considered her talent for amazement at once the most ‘authentic’ kind of philosophy and a form of ‘philosoph ical poverty’, meaning perhaps that it did not lead anywhere and was insufficiently developed and conceptualised. He added, in a phrase that reflects his Heidegger-reading at the time, ‘it’s the moment at which the question transforms the questioner’.

Of all the things Beauvoir wondered at, one thing amazed her more than any other: the immensity of her own ignorance. She loved to conclude, after early debates with Sartre, ‘I’m no longer sure what I think, nor whether I can be said to think at all.’ She apparently sought out men who were brilliant enough to make her feel at a loss in this way—and there were few to be found.

Before Sartre, her foil in this exercise had been her friend Maurice Merleau-Ponty. They met in 1927, when they were both nineteen: she was a student at the Sorbonne, and Merleau-Ponty was at the École normale supérieure, where Sartre also studied. Beauvoir beat Merleau-Ponty in the shared examinations in general philosophy that year: he came third and she came second. They were both beaten by another woman: Simone Weil. Merleau-Ponty befriended Beauvoir after this because, according to her account, he was keen to meet the woman who had bested him. (Apparently he was less keen on the rather formidable Simone Weil — and Weil herself would prove unenthusiastic about Beauvoir, rebuffing her attempts at friendliness.)

Weil’s and Beauvoir’s results were extraordinary considering that they had not come through the elite École normale supérieure system: it was not open to girls when Beauvoir began her tertiary education in 1925. It had opened to female students for just one year, in 1910, before closing the doors in 1911 and keeping them shut until 1927 — too late for her. Instead, she attended a series of girls’ schools which were not bad, but which had less exalted expectations. This was just one of the many ways in which a woman’s situation differed from a man’s in early stages of life; Beauvoir would explore such contrasts in detail in her 1949 book The Second Sex. Meanwhile, all she could do was study furiously, seek outlets in friendship, and rage against the limitations of her existence — which she blamed on the moral codes of her bourgeois upbringing. She was not the only one to feel this way. Sartre, also a child of the bourgeoisie, rebelled just as radically against it. Merleau-Ponty came from a similar background, but responded to it differently. He could enjoy himself quite happily in the bourgeois milieu, while pursuing his independent life elsewhere.

****

For Simone de Beauvoir, independence had come only after a battle. Born in Paris on 9 January 1908, she grew up mostly in the city, but in a social environment that felt provincial, since it hedged her around with standard notions of femininity and gentility. Her mother, Françoise de Beauvoir, enforced these principles; her father was more relaxed. Simone’s rebellion started in childhood, became more intense in her teens, and still seemed to be going in adulthood. Her lifelong dedication to work, her love of traveling, her decision not to have children, and her unconventional choice of partner all spoke of total dedication to freedom. She presented her life in those terms in the first volume of her autobiography, Memoirs of a Dutiful Daughter, and reflected further on her bourgeois background later in her memoir of her mother’s last illness, A Very Easy Death.

It was while she was first beginning to strike out alone as a student that she met Merleau-Ponty through a friend. She noted her impressions in her journal, calling him ‘Merloponti’. He was attractive both in personality and in looks, she said, though she feared he was a little too vain about the latter. In her autobiography (where she gives him the pseudonym ‘Pradelle’), she described his ‘limpid, rather beautiful face, with thick, dark lashes, and the gay, frank laugh of a schoolboy’. She liked him at once, but that was not surprising, she added. Everyone always liked Merleau-Ponty as soon as they met him. Even her mother liked him.

Merleau-Ponty was just over two months older than Beauvoir, born on 14 March 1908, and much more at ease with himself. He sailed through social situations with a relaxed self-possession which (as he himself thought) was probably the result of having had a very happy childhood. He had felt so loved and encouraged as a child, he said, never having to work hard for approval, that his disposition remained cheerful for life. He could be irritable sometimes, but he was, as he said in a radio interview in 1959, almost always at peace with himself. This makes him about the only person in this entire story who felt that way; a valuable gift. Sartre would later write, apropos Flaubert’s lack of love in childhood, that when love ‘is present, the dough of the spirits rises, when absent, it sinks’. Merleau-Ponty’s childhood was always well buoyed up. Yet it cannot have all been as easy as he liked to imply, since he lost his father in 1913 to liver disease, so that he, his brother and his sister grew up with their mother alone. Where Beauvoir had a strained relationship with her mother, Merleau-Ponty remained utterly devoted to his for as long as she lived.

Everyone who knew Merleau-Ponty felt the glow of well-being emanating from him. Simone de Beauvoir was warmed by it at first. She had been waiting for someone to admire, and it seemed he would do. She briefly considered him as boyfriend material. But his relaxed attitude was disturbing to someone of her more combative disposition. She wrote in her notebook that his big fault was that ‘he is not violent, and the kingdom of God is for violent people’. He insisted on being nice to everyone. ‘I feel myself to be so different!’ she cried. She was a creature of strong judgements, while he looked for multiple sides to any situation. He considered people a mixture of qualities, and liked to give them the benefit of the doubt, whereas in youth she saw humanity as consisting of ‘a small band of the chosen in a great mass of people unworthy of consideration’.

What really irked Beauvoir was that Merleau-Ponty seemed ‘perfectly adapted to his class and its way of life, and accepted bourgeois society with an open heart’. She would sometimes rant to him about the stupidities and cruelties of bourgeois morality, but he would calmly disagree. He ‘got on perfectly well with his mother and sister and did not share my horror of family life’, she wrote. ‘He was not averse to parties and sometimes went dancing: why not? he asked me with an innocent air which disarmed me.’

In their first summer after becoming friends, they were much thrown on each other’s company, as other students were away from Paris for the holidays. They went for walks, first in the gardens of the École normale supérieure — an ‘awe-inspiring place’ for Beauvoir — and later in the Luxembourg Gardens, where they would sit ‘beside the statue of some queen or other’ and talk philosophy. Notwithstanding the fact that she had overtaken him in the exams, she found it natural to take on the role of philosophical novice beside him. In fact, she sometimes won their debates, almost by accident, but more often she was left happily exclaiming, ‘I know nothing, nothing. I not only have no answer to give, but I haven’t even found a satisfactory way of propounding the questions.’

She appreciated his virtues: ‘I knew no one else from whom I could have learnt the art of gaiety. He bore so lightly the weight of the whole world that it ceased to weigh upon me too; in the Luxembourg Gardens, the blue of the morning sky, the green lawns and the sun all shone as they used to in my happiest days, when it was always fine weather.’ But one day, after walking around the lake in the Bois de Boulogne with him, watching swans and boats, she exclaimed to herself, ‘Oh, how untormented he was! His tranquillity offended me.’ It was clear by now that he would never make a suitable lover. He was better as a brother figure; she only had a sister, so the role was vacant and perfectly suited to him.

He had a different effect on her best friend, Elisabeth Le Coin or Lacoin (called ‘ZaZa’ in Beauvoir’s memoirs). Elisabeth too was unnerved by Merleau-Ponty’s ‘invulnerable’ quality and his lack of anguish, but she fell for him passionately. Far from being invulnerable, she was prone to emotional extremes and wild enthusiasms, which Beauvoir had found intoxicating during their girlhood friendship. Elisabeth now hoped to marry Merleau-Ponty, and he seemed keen too — until he suddenly broke off the relationship. Only later did Beauvoir learn why. Elisabeth’s mother, thinking Merleau-Ponty unsuitable for her daughter, had warned him to back off or else she would reveal an alleged secret about his mother: that she had been unfaithful, and that at least one of her children was not her husband’s. To prevent a scandal engulfing both his mother and his sister, who was about to get married, Merleau-Ponty bowed out.

Beauvoir was even more disgusted after she learned the truth. How typical of the filthy bourgeoisie! Elisabeth’s mother had shown a classic middle-class combination of moralism, cruelty and cowardice. Moreover, Beauvoir considered that the result literally proved lethal. Elisabeth had been very upset, and in the middle of the emotional crisis she caught a serious illness, probably encephalitis. She died of it, aged just twenty-one.

There was no causal connection between the two disasters, but Beauvoir always thought bourgeois hypocrisy had killed her friend. She forgave Merleau-Ponty his role in what had happened. Yet she never ceased to feel that he was too cosy and respected traditional values too much, and that this was a fault in him — a fault she swore never to allow into her own life.

****

A little after this, Beauvoir’s ‘violent’ and opinionated side got all the satisfaction it craved when she met Jean-Paul Sartre.

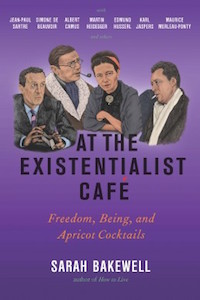

From AT THE EXISTENTIALIST CAFÉ. Used with permission of Other Press. Copyright © 2016 by Sarah Bakewell.