At the Autograph Show: Finding Peace in Saying No to My Mother, Tatum O’Neal

Kevin McEnroe on His Mother’s Struggles with Addiction

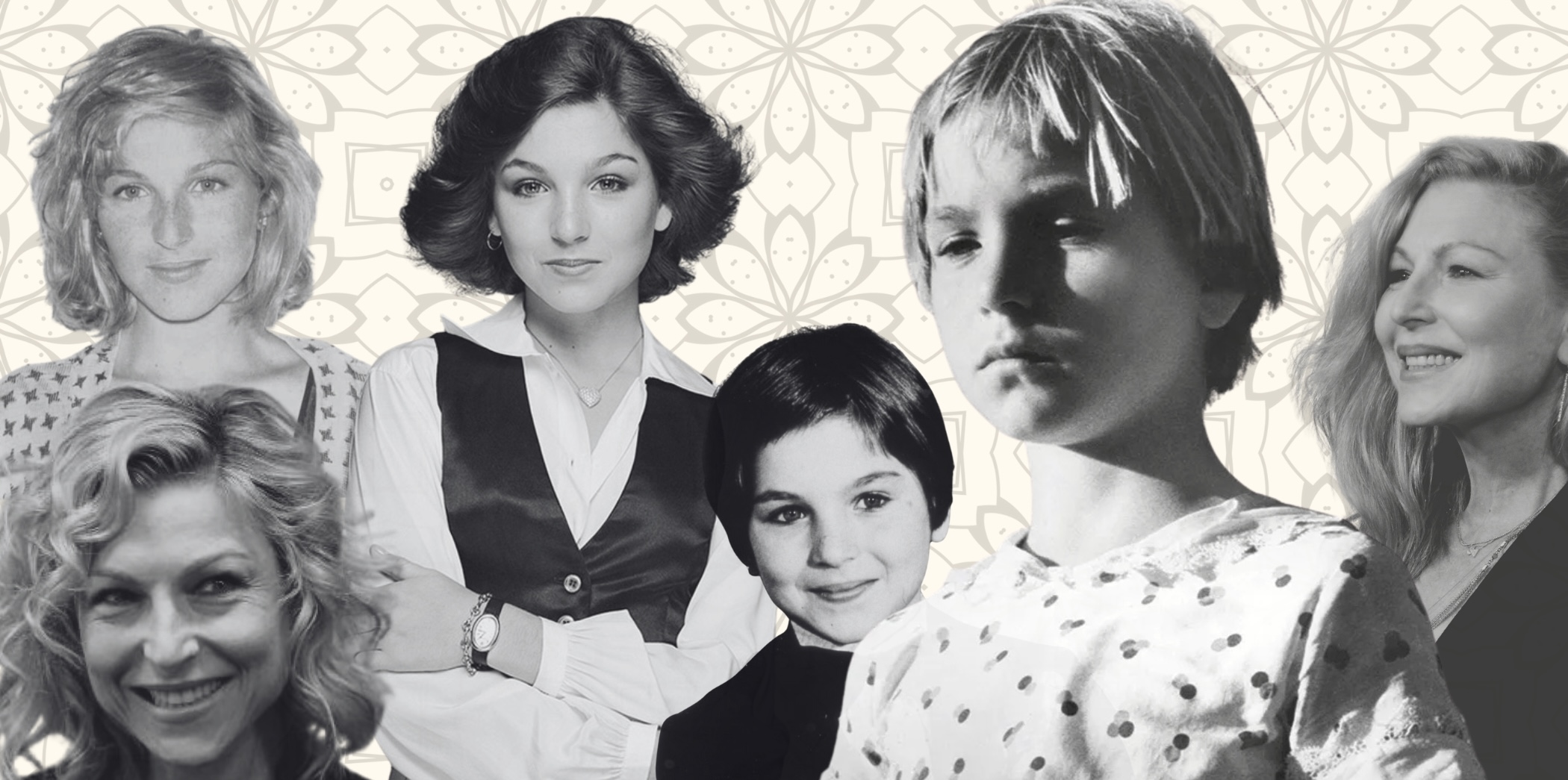

My mother used to draw these pictures when I was little and she was high.

My sister and I would sit there with her and draw, too. My mother loved to be around my sister but my mother couldn’t not use drugs. It created lovely long lunches like this.

My mother had an autograph show in September. She can no longer read or write, but she can sign her name—the celebrity part of her brain remains relatively untouched. She’s still Tatum O’Neal, the actress, after all, which is how she used to introduce herself when she made reservations. She still gets her nails done bi-weekly, by a woman who comes to her, who I have to Venmo. She gets her hair done at the fanciest place in West Hollywood, sometimes near Rihanna. When she gets nervous she needs to be more blonde. She vapes in the Uber, even when they ask her not to. She wants what she wants when she wants it, and she makes “no” feel impossible.

In certain respects, my mother’s stroke, caused by a drug overdose—most of which was prescribed, everything except the meth—has made her the mother I always hoped for. She’s relatively reliable, and accountable. She’s full of love—she’s a fan. I know where she is, and what she’s doing. She cares and she listens, and sometimes she asks how you’re doing, too, and not because she knows she’s supposed to, and not because if she queries then you might be more willing to ask her.

An addict doesn’t not love you, at least in my mother’s case, but an addict robs from you your peace of mind, and they can’t see it.

Because she wants to know. I always knew that was in there—in her. I remember it from when I was a kid, before drugs were prescribed by doctors, and so there was using, or there wasn’t using, and there was clean time, and some of those times were mom times. These usually coincided with periods where she seemed to forget to blonde her hair. And she always, with her kiddos, looks so happy.

And she’s safe. Most importantly, she’s safe. My whole life I thought if I wasn’t around then something bad would happen, because it usually did. Once, I was supposed to visit her over spring break or something, but I had just fallen for a girl and I wanted to take her on a trip. When I got back my mother had overdosed, again, and was in the hospital, and she told me it was my fault. If I had only visited, then this wouldn’t have happened.

An addict doesn’t not love you, at least in my mother’s case, but an addict robs from you your peace of mind, and they can’t see it. You always think the moment you leave them alone that they’re in danger. You monitor their moods—having to take their temperature—because if it falls below a certain degree on the thermostat something like thunder rolls in, and then rain, and it’s difficult to find shelter. I still feel this sometimes, even though I know she’s okay. It’s impractical—unintellectual—but it’s in your bones.

I don’t fight off how I was raised anymore; I don’t run from it. It is neither entirely that I’m traumatized, and need to spend my life healing, or rub some dirt on it, and quit complaining, but both. Embrace the parts you like, change the parts you don’t. I’m attentive, and caring. My mom taught me how to love, and I love big, and I feel big, but that’s okay, too. My life doesn’t have to hinge so much on feelings. I can feel things I don’t like and survive them. I steady my boat, so if I have to reach in the water and grab someone up, they can’t pull me in with them.

I still get nervous when I don’t order the right things for her on Sundays, but only because she won’t leave me alone till I get it right. She currently is in dire need—“now would be best”—of Yerba Mate tea bags. She gets disappointed and scared when she’s running out of vapes. You begin to understand why it may be ever more complicated—or at least different complicated—for celebrities to get clean, because people just don’t say no to them very often. When I go out to dinner with my dad, no matter where we go, he stares over his reading glasses for a while—I guess pretending to scour the menu—before ordering something that he likes to eat at home, that definitely wasn’t written anywhere before him.

“How about like some, uhh, sliced mozzarella with a bit of prosciutto, a couple of pastas—bolognese if you have it—steamed broccoli, and some brown rice?”

I always shake my head, hoping that they’ll say we don’t have that, but they always say yes. Sometimes I imagine a manager running to the back of the house and telling one of the bus boys to go to the nearest Gristedes and buy brown rice, broccoli, and maybe even easily sliceable mozzarella cheese, because they’ve already accounted for the cheese in house for the dishes that they have to make. The bus boy comes back sweating, with a plastic bag tied to his forearm, having biked the six blocks back and forth from the only 24-hour supermarket in the area, just in time for my dad to be looking at his watch while they drop his custom order before him, somehow frustrated that it isn’t quite as he’d imagined it should be.

The best part of being a celebrity, it seems to me, is that sometimes you can make someone else’s day, and my mother knows that.

The point I’m making, fundamentally, has very little to do with the way my mother is only just starting to hear no, as she’s become a person, or that my dad still doesn’t much, outside of his wife and his daughters, who, thank god, NO him eternally, but just that the heartbreak that this causes Academy Award-winner Tatum O’Neal might be saving her life, and mine. My refusal to buy her vapes is teaching her that she can’t get whatever she wants whenever she wants it—which is, for some, the definition of addiction—and it teaches me, again, how to say no. What’s right and what feels good are most often not the same thing, and often opposite things. Sometimes after you do what’s right you feel better though. Perhaps that’s integrity, and perhaps that’s what leads to the sustainability of being grown up.

And so back to the autograph show, where other very grown-up former stars find ways to pay for their surgery co-pays and concierge psychiatrists. My mother used to do these in the 2010s as the money got thin. When I was in the hospital, she flew to New York and held my hand while got my vitals read every few hours. She was mired in her own issues as she sat by my bedside, wearing surgical gloves to protect her from the mites she had decided were burrowing through her skin, so it wasn’t necessarily a meeting of the minds. I was there for a month, and she watched 90 Day Fiancé beside me, but what I didn’t know was that she was staying at a nearby hotel, and that it wasn’t a cheap hotel. On the back end, she had an autograph show to do. This is how she planned on paying for said month-long stay at her suite.

This is how she lived her life. Money was spent—we’d figure it out later. Before she overdosed, the last time, the stroke time, my mother had spent almost all of her money buying dresses from Marni online, because I think she’d decided that there wouldn’t be a later. But she made it, and there are still beautiful dresses. I think my sister wears them. She’s been through a lot. She deserves it.

I got a call the other day from an old lady who claimed to be organizing the event. She called me from a landline—a 310—with her 90-year-old husband on the other line in the kitchen, to explain that they would send a car—I believe they even said stretch limo—provide the images for her to sign, and take care of her. Sometimes I wonder how these people get my number, but it usually comes back to money. When there’s money involved they tend to figure it out.

My mother’s hair is dark, and she sits in her chair, most of the day, doing Zoom meetings and watching episodes of The First 48 between airings of Meet the Press. Not always happy, but content. But she gets to feel like a star again, and, even though it might pull on her equanimity, I think she’s ready for that not to be her everything.

I was here when they did a photoshoot for Variety. My mother was great that day. She lit up with the camera on her. She smiled and that smile rolled past her shoulders and then hit the ground like a wave, and the water from that wave washed over, and, for some—for me—through—the onlookers, the fans, who watched her. Her smile—the moneymaker, the parasite—infected us all, and I thought to myself—“my mother’s great at this.”

The best part of being a celebrity, it seems to me, is that sometimes you can make someone else’s day, and my mother knows that. She lets in sunshine, but only for you to feel. She can make your day, and will, so you let her, even if it sometimes hurts. If your boat’s strong enough to withstand the tide, which is really hard to do and requires a lot of patching, why not try and pull ‘em all up.

Kevin McEnroe

Kevin Jack McEnroe is the author of the novel Our Town. He was raised in New York and received an MFA from Columbia University. He currently lives in the Hudson Valley with his wife and dog, Sunday. https://substack.com/@kevinjackmcenroe