Well worth it, well worth it, the last of the legendary glaciers and cell phone service besides. They have seen a wolf and bighorn sheep and a hundred cheeping pikas in the rocks and a pair of boxing marmots.

But the littlest is a little let down. They have to get back to Ohio, back to the hover-mother and school. He has to pee. So bad. He can’t stand it. So the father pulls off at Sunrise Gorge. There’s a waterfall and people around. Soon the water is falling in the sunlit gorge and the little boy is peeing on a little rock and the big brother pees on a bigger rock and the father has his out, too.

Here a bear appears from between the trees and stands a while to watch them. It’s just watching.

They can’t pee anymore. They have waited so long to see a bear they can scarcely even believe it’s a bear.

“It’s a bear,” says the bigger boy. The father says, lowly, “Boys.”

It will eat me first, thinks the littler boy, and the bear thinks, Indeed.

The father makes a gutsy father sound and stands his ground bravely between the bear and his boys and the bear leaves the path to trot around him. The bear wants that little boy. That boy is doing exactly what his father says and walking backward toward the Escalade but the bear is trotting frontward at him. The boy turns and runs, which you are not supposed to do, but, lucky boy, because the bear turns and opens his mouth at the other brother.

Don’t run, say the pamphlets, don’t shout.

“Don’t run!” shouts the father and now the other brother is running too and you can bet if they hadn’t peed three seconds ago, they would all be peeing now. The bear is closing in on the bigger boy, the bigger boy is the father’s favorite boy, it’s true. The father runs shouting down the path at the bear with his car keys scratching in his pants.

At last the Escalade.

But the doors are all locked, the littlest boy tried, so the boys try diving under the car. The bigger boy is giggling now, it makes no sense but so what.

A crowd has begun to gather, oh, a bear, they have waited so long to see.

The bear takes a swipe at the boys beneath the car. The boys roll across the gravel to the other side, so the bear trots over to the other side and takes a swipe and they roll off again.

The crowd loves it, how like a circus, stupid but you have to admit.

The father shouts and waves his arms and the hover-mother sips iced tea with a sprig of mint with the shades cinched tight while her boys roll fast and away from the face and the terrible yellow claws of the bear and the dreadful meaty breath of the bear and the little one bleeds, nicked in the ribs, and socks his brother for laughing.

The father makes a claw with his car keys thrust between his chubby fingers—to do what, he doesn’t know, go for the eyes, but instead he whips his keys at the bear’s awful face—you guessed it, the car is still locked.

A button springs out from the little boy’s shirt and turns like a top and lies down.

But let’s keep to the bigger picture, to the sipping and swiping and the stone the father heaves and at last to the father on the hood of his car, his beautiful car, at last to the father on the roof of his car, Bluetooth and drop-down screens and, my God, the chrome, the leather, but what passes now through the vast mind of the bear we will never know.

Pity, disgust, despair?

A bush of ripened berries? A juicy beetle? Bees? We can’t know—what a shame, we would like to.

Happily our story stops here. The bear takes a last swipe across the hood of the car and leaves a mark in the luminous pearl they will decode the miles home to Ohio. The mark is a bigger version of the mark on the littler boy’s ribs.

The father takes it to mean: buckle down. He quits carousing. He finds a job he can stand not to hate every day and loves his boys like a crazy man he never was before.

NOW, the day shouts. BE SOMETHING.

Be free, one boy thinks, in a flap tent. Be a bird in an eaten tree. He plans to fell his first goat with a bow he carved and pack the meat out in a rucksack in bloody, cooling slabs. Forage for parsnips and mushrooms. For luck, he will carry that button. For love, he relies on a chickadee who lights on his steady hand.

For now, he’s still under that Escalade his father is pounding on.

His poor father has yanked his shirt off and he is flapping it like a rodeo clown, oblivious at last to his beautiful car and his ugly patchy blubbery gut—it’s alarming, but that’s the idea. He has bloodied his nose with a button. He is shrieking like a peacock and sobbing and clutching himself in the chin.

The bear rears up and walks into the shade like a man he never hopes to be, and a woman claps, uncertain—applause—no lonelier sound in the world.

My heart, my heart, the father sobs, and the sobbing sounds like choking, which it sort of is.

In a minute every tonto watching will hurry off not to miss the nightly feature, happy hour, buffalo tongue, lucky us, we can eat them again, snatched from the brink of extinction. Yippee.

__________________________________

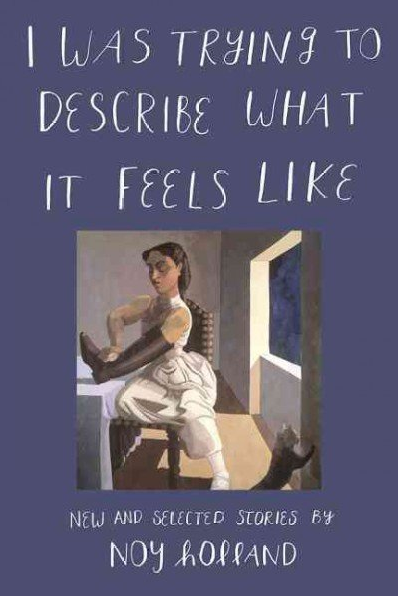

From I Was Trying to Describe What It Feels Like. Used with permission of Counterpoint Press. Copyright © 2017 by Noy Holland.