Assimilation and Erasure: How Imposter Syndrome Traps People of Color

Prisca Dorcas Mojica Rodríguez on the Inherent White Supremacy of Ivory Towers

I understood in high school that other people did not see potential in me, but somehow I saw potential within me. Even when I was able to do things that were firsts for my family line and ancestors, I had little doubt internally in my own ability to do well. There was a spark within me that was probably naivete, but also some willpower that I was able to harness.

But then in my twenties I moved to the primarily white city of Nashville, Tennessee. And in this white city, I began to see that people had different expectations for what I was capable of, and there was no one around that looked like me to prove to me and my brain that I could defy those odds. It was not until later in life that I would develop the skills to create my own spaces for representation, like Latina Rebels.

Impostor syndrome is something that almost everyone experiences at some point in their lives. Impostor syndrome is the name for that fear that people will one day discover you to be a fraud. It is the lingering doubt that you are not worthy of your successes. This type of thinking can have negative effects on your mental health, which in turn can affect your physical health.

Impostor syndrome is believed to affect all genders, but early on when the phrase was first coined and gaining currency, it was discussed as a common experience among women in the workplace. I will further Pauline Rose Clance’s theory that it was specifically a white woman problem, because they were among the first to infiltrate the white male corporate world. Women are socialized to be docile, appeasing, welcoming, humble, not opinionated, and deferential to men. Men are socialized to be aggressive, competitive, bold, and proud; they are groomed for power, dominance, and success.

When women began to be recognized for their professional successes, impostor syndrome led them to believe what they had been socialized to believe—that any accomplishments resulted from luck, teamwork, and outside help.

People of color and specifically BIWOC can suffer impostor syndrome in the same ways, but also differently. Society applauds whiteness for the sake of whiteness, and expects greatness from white people, though still within a two-gender hierarchy. These cultural values are affirmed through media, literature, academia, interpersonal interactions, the entertainment industry, and so on. Performing well professionally for BIPOC requires overcoming low expectations; if you do well, white peers now believe you are an exception to a cultural rule. Racial impostor syndrome comes from fears that you will be discovered as a fraud. But the racial dynamics are complex, because you are made to believe that you don’t belong—whether you succeed or fail.

While Black and Latino students are not intellectual frauds, the education system often transmits messages that suggest the opposite. A belief that intelligence is inherited and “fixed” and using culturally incongruent measures that continue to illustrate, symbolically, a hierarchy of intelligence will only continue to reinforce cognitive misrepresentations.

–Dawn X. Henderson

I started to experience intense impostor syndrome in my graduate program. At my undergraduate university, Florida International University, I had graduated at the top of my class. I made the dean’s list almost every semester, and I had a side business of writing papers for people for money. I could ensure an A or B grade to all my clients. I felt pretty invincible in my Hispanic-Serving Institution; I felt seen in my undergraduate experience because I felt validated through grades and accolades. I adapted to college very well, despite being the second person in my family to attend college in the United States and having to learn to maneuver this space without much guidance. Seeing professors who spoke broken English with heavy Spanish accents meant that I saw myself through hearing the familiar.

Performing well professionally for BIPOC requires overcoming low expectations; if you do well, white peers now believe you are an exception to a cultural rule.

But still, I had been on my own to figure out the FAFSA, college applications, credits and electives, and what coursework was required for majors and minors. And it was touch and go for a bit, as it was hard to figure out and even harder to explain to people why I did not already know some things.

Still, I had managed to do well. So well that I thought, “Why not try graduate school?” in a flippant way that I can only describe as Elle Woods–like. I felt so reassured and valued, through representation and grades, that I managed to somehow see a place for myself within academia. Even when I did not really know what grad school entailed and who was there guarding the entrance.

I did not score well on my GRE, because standardized tests are racist, classist, ableist, and designed to weed out those who do not belong inside the pristine walls of academia. Still, I was able to find a program that knew those flaws in standardized testing, and I was admitted into an elite graduate institution: Vanderbilt University in Nashville, Tennessee. But the process of being admitted marked the entire academic experience for me.

I had great recommendations, I had a 3.5 GPA from undergrad, I had served in leaderships positions in various honor societies, and I had also written a thesis for my honor’s college requirement. On paper, I should have been a shoo-in. And then I received this phone call from the admissions director at Vanderbilt Divinity School. On this phone call, I was asked to explain my statement of purpose. As a first-generation student, I did not have much knowledge in terms of what a statement of purpose was supposed to be, and I certainly couldn’t get help from my family or friends. I just did what I had always done, and that was ask the internet and hope for the best. I had googled how to write one.

I then wrote about my desire for a theological education. When I explained my statement of purpose to the admissions director, she gave me the acceptance over the telephone. I had been accepted without ever having received an admissions letter. I had been accepted into Vanderbilt Divinity School through a screening process.

I remember being confused about this phone call. I also remember being shocked and elated that I had been accepted to this prestigious program. I was so caught up as a first-generation student that I did not question the process that I had just undergone. Many months later, during our new-student orientation, I remember asking other students how they were accepted—because by that point I had had more time for doubt to seep in. The process that I had undergone felt off, and I didn’t know why I was screened. So, I sought out answers, and in asking around I discovered no one else I asked had been called.

Also, I was one of only two self identifying Latinas in my cohort of seventy or so graduate students. The other Latina is mixed, and she had attended Duke University for her undergraduate program. In my mind, I thought maybe I was screened because I had attended a large state school (FIU enrollment at the time was more than forty-five thousand students) as opposed to a small and elite private university. But these were all speculations.

The more I asked people if they were screened, the more strange looks I got, and the more I was convinced that my peers now knew what I assumed they had already suspected: that I did not belong. Perhaps the university, and my cohort, knew something I had not yet fully discovered within myself. That screening process should have been the red flag for my journey ahead at Vanderbilt University.

I couldn’t help but see that message—you do not belong—everywhere. I once mispronounced a word, which I had only ever read but had never heard said out loud, in a question during a lecture, and my professor giggled and corrected me under his breath, in front of the entire class. I remember being asked if I even knew how to write, by a teaching fellow in a discussion group in front of twenty of my peers. I remember my classmates using obscure academic references I had never heard before. That lingering feeling, that seed of doubt that had been planted during that screening call, that seed began to grow roots within me.

When faced with a need to perform, [impostors] experience doubt, worry, anxiety, and fear; they’re so afraid they won’t be able to do well that they procrastinate and sometimes feel they’re unable to move at all toward completing the task. In other cases, they overwork and overprepare and begin much sooner than needed on a project, thus robbing themselves of times and effort that could be

better spent.

–Pauline Rose Clance

As a way of managing my growing impostor syndrome, I began to overprepare. I would tell professors about my proposed thesis for our final paper during the first few weeks of school, and it became a running joke among my peers. In my attempt to assert my worth, I was ridiculed. There was a lack of understanding from my peers in what it meant to be the first in my family to achieve this level of academic success, and a lack of understanding of what it meant to enter elite spaces that signal your “otherness” often.

I also began to self-sabotage. During my second semester of my first year, I got a B on my first exam for our New Testament class. Most students had failed this exam, and the professor told everyone that a C grade from her was equivalent to an A grade for any other class. Those words haunted me, and I never got a better grade from that teacher. I remember wanting to get a handle on my worth, and wanting and trying to do better, and yet continually getting Bs and Cs. The A grades were elusive, and I blamed myself. I was exerting myself beyond what I knew to be my own capacity, and I still felt like I was grasping at straws. I felt like a fraud.

I was reading books my peers had already read in undergrad, and I was researching theories my peers had already studied years ago. I was playing catch-up, and I blamed myself. I had been taught, and had believed in, things like perfectionism and meritocracy—teachings that made me believe there was only one right way to do things, and that hard work paid off. None of that served me when I was trying my hardest and doing my damnedest and still could not compete in this academic environment.

You see, what was missing was that I was trying to find my worth and validation from an institution designed for white intellectuals. The ivory tower is ivory for a reason; it is not ebony, it is not the color of honey, nor the color of café con leche, and I was never meant to thrive there. Until I understood that my validation was not going to come from my predominantly white institution (PWI), I was going to keep struggling.

But back then, I was not well versed in white supremacy and the various systems that uphold it. I had none of the advantages that my peers had from their white privilege; no tutors, no private education, no SAT or GRE courses, no network of family members who had gone to elite universities. My lack made my professors and peers uncomfortable, and I was constantly made to feel that I didn’t belong and that any time I fell short I confirmed their suspicions. My modest grades became a marker of my otherness. And my body began to show the signs of buckling under all these pressures.

I began to experience palpitations, and I would sweat through my clothes from anxiety when talking to any person with power, which usually meant that they were white. I felt misunderstood and weird. I could not sound brilliant enough, and I could not bolster my arguments with enough citations, and I could not seem to make sense to my peers, and I began to shrink right before their eyes. When I had once felt invincible, I began to want to be small, to be invisible. It felt like I was in an abusive relationship with an institution, seeking its validation and only receiving criticism, and none of that made sense to me.

Impostors are very perfectionistic in almost every aspect of their performances.

–Pauline Rose Clance

My impostor syndrome came from internalizing white-supremacist models of meritocracy and perfectionism. White supremacy promotes the idea of individualism, because that keeps us busy and unfocused on what the real problems are. Through individualism we do not analyze the systemic problems, the institutions that keep so many of us down. Because of individualism, I was unable to see that this was not about me, but about us all. Our wins are ours, and our losses are ours, and they belong to our communities who encourage us. When we don’t seek white approval in PWIs, we can look to our Black and Brown peers and our chosen family, who show us how to resist and how to be seen by one another.

The ivory tower is ivory for a reason; it is not ebony, it is not the color of honey, nor the color of café con leche, and I was never meant to thrive there.

Because I was not yet aware of how much racial impostor syndrome impacts us all and how much white supremacy can infiltrate your sense of worth, by my second year of graduate school I had developed an eating disorder. I felt like I could not control how others saw me, so I spiraled. I felt that when white people saw me, all they saw were my flaws, and I experienced that to be true. It was not just a feeling, it was happening and it was true. So, I began to shrink my body. I wanted to take up less space. I felt that I couldn’t be good enough, and the white gaze felt suffocating. Waiting for validation from white people was sucking my ability to value myself outside of their gaze.

I tried to escape the voices in my head that told me I did not belong. American society dictates that whiteness, and proximity to whiteness, was always going to be the measure of success. I was starting to learn about racism, sexism, and classism, and slowly I began to find the language for the forces around me. But while my brain and my lips could finally name the oppression, my heart still hurt from feeling like an outsider all the time, all while trying to graduate.

Two years later, I would develop a mentorship relationship with the admissions director who I had spoken to in that screening call. And I asked her directly why I had been screened before attending. By this time, I had often been made to feel inferior by my peers and professors. I knew that there was an underlying presumption of my incompetence, and I was in search of real answers.

When I asked her about being screened, she told me it was not because of my grades or competence. The school wanted to know that I was willing to learn and grow in my theological training. My statement of purpose reflected my charismatic Christian, fundamentalist, conservative upbringing. Some students with my background are resistant to learning progressive theologies, and Vanderbilt Divinity School saw itself as a progressive theological institution. I did see students on campus from conservative backgrounds who seemed like they were fighting the program, and those people felt like outcasts. Then again, I also saw people struggle who had liberal backgrounds, so that screening process was not free of faults. Knowing the reason should have alleviated my initial fears, but by this time it was too late. My self-confidence had been worn away by years of negative messaging within my PWI, and the damage would affect me in ways that I would only discover much later.

We rarely have control of the ways impostor syndrome traps people of color. To assimilate requires erasing your ethnicity; you have to perform in a way that puts white people at ease, to the point where you earn honorary whiteness: “You’re not like the others.” Students like myself who choose not to erase their ethnicity, or who cannot downplay their differences, are othered and quietly outcast. Succeeding through Americanized, white definitions of success means performing to reinforce, or to spite, the greatness of whiteness. We either reinforce or upset the low expectations built by white supremacy. And many of us develop anxiety and other mental illnesses when we are daily asked to compromise ourselves, all while trying to juggle schoolwork, or do our jobs, or live our lives. We dared to believe that degrees and promotions meant success, but no one ever said that success came at the cost of our well-being.

By the time I graduated, despite knowing that the screening process was not meant to delegitimize me, it had. That one seed that had sprouted roots had become a full ecosystem by the time I got home from graduate school. And while my mind and my lips can consistently articulate the ways that I know impostor syndrome was something that was cast onto me, I still cannot shed it.

_____________________________________________________

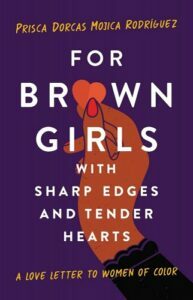

Excerpted from FOR BROWN GIRLS WITH SHARP EDGES AND TENDER HEARTS: A Love Letter to Women of Color by PRISCA DORCAS MOJICA RODRÍGUEZ. Copyright © 2021. Available from Seal Press, an imprint of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

Prisca Dorcas Mojica Rodríguez

Prisca Dorcas Mojica Rodríguez is a writer and activist working to shift the national conversation on race. The founder of Latina Rebels, her work has been featured by NPR, Teen Vogue, Huffington Post Latino Voices, Telemundo, and Univision. She was invited to the Obama White House in 2016 and has spoken at over 100 universities in the past three years. She lives in Nashville, Tennessee.