Carolyn (1988)

The town of Ashland rises between two rivers, but you’d never know it. Driving northeast from here to Holderness you sidle along Squam River, then Little Squam lake, and there’s that feeling of being beside water. Going the other way, northwest towards Plymouth, you cross a high steel bridge over the inexhaustible Pemigewasset just outside of town, and again there’s the nearness of the river and the feeling of a moving body of water that is traveling with you. South of town, Rte. 3 finds the Pemigewasset again and there are some campgrounds with river rafting and tubing. But here, on Main Street and all around the town, it is a darkly kept secret that we’re bounded by water on three sides.

Outside of town what you see mostly are farmhouses and New England homesteads. In town there are rooming houses and cottages for one or two families, built for millworkers. Up on Highland Street are some fine mansions. Along Main Street, the ground floor windows are low and tall in the old brick edifices, and there are wide granite steps where I like to sit sometimes. There’s just something halfway about the town. Halfway victories, halfway defeats, not necesssarily sad but for the halfwayness itself. People always telling you how important school is, but it doesn’t prepare us for the things we’ll actually go and do when we’re done. We’re mostly wasting our time here. And then you graduate.

I am sixteen and a sophomore when I sign up for my first writing workshop at Plymouth State, technically as an auditor so I don’t have to pay. It meets twice a week right after school lets out. I take the bus from Ashland and then run the last part of the way, not to be late. The other students are older, but that doesn’t mean anything to me. I remember my first impression of Geoff standing at the blackboard spelling his name. It is as if every other strange thing I’ve ever seen moves aside to make room for the strangeness of him.

After a little while he walks over to the door, closes it and starts talking to us on his way back to his desk. Geoff’s body is weird. Something about how he moves. He’s tall, and his body is loose, almost too loose. I stare at him on the first day, trying to understand, thinking for some reason that his body language is saying the same things he is saying with words in his introductory speech, which I am already struggling with. He moves like a friendly monster. Peaceful and at the same time ruthless, his soft voice and the gentle cast of his eyes, together with the feeling that he doesn’t suffer fools.

It turns out he’s an avid reader of our work. At the end of each week we give him our pages, and when he arrives for the next class it’s with a fire in his eyes and his hands clasping the bundle of pages to his chest. My classmates are an odd group: people who want to write, but who know they’re probably not going to go far, because they don’t have any of the advantages.

Geoff takes me to be sui generis, he says, by which I understand him to mean I’m a local creation, like New Hampshire maple syrup, and in my writing I don’t seem to be imitating anyone in particular. He tells me the second week of class that he hasn’t seen one like me before and doesn’t think he ever will again. He looks happy when he says that. He thinks I have talent coming out of my ears. And how rare genuinely gifted people are. He says most people would never want to be writers if they had any idea what it takes. He also says most of those that really are gifted have fantasies of being just like everyone else. His actual words are, That’s what we mean by success. It means talented people being rewarded so that they can have the things that everyone wants and in that way become normal.

I’m sixteen. I don’t really think he should be saying any of these things to me. But I like him because he is just saying what comes into his head, not censoring himself. I don’t think he’s trying to be nice just for the sake of being nice. I’ve never met someone before who thinks I’m talented.

*

I grow up reading books. I’m always stopping by the Ashland Town Library after school. I know people will say they were changed by one particular book they read. But for me it isn’t like that. I read everything I can get my hands on. There’s no one book. Mostly, I’m not even reading good books, never mind great ones. No one tells me anything. I read romances and laugh out loud. I mean they’re just so funny! I like reading mysteries. Ellery Queen! But almost nothing I read feels very real to me. Mostly, I’m just seeing how other people tell stories, keep you interested, say more than they should and more than they have to. To me, well, writing just means saving stuff, socking it away, like having a bank account of precious observations and memories. It means unpacking silences, that most of all, and seeing what silences are made of. It means teasing the individual threads apart—deconstructing, wrecking, destroying.

If you think of music as the spaces between the notes, that’s what writing means to me. I read so many books of all kinds that hardly seem written to me.

*

Look at the mountains, just look at them. That’s how long it takes to do anything that will last. It isn’t any different for us. We need many, many lifetimes. But we only get one. To me, my afternoons reading, with my father’s mother in town sometimes, beside mama a lot, with Edith, the afternoons reading with these women I trust completely, is as close as I could ever get to the other side of the problem of living, and that’s writing. You watch the stories unfold. Reading is something we do, a spiritual exercise. With Geoff, I’m having this experience with a man for the first time. My brain resists this and my heart resists this. I am synchronized in my refusal of the idea of a man being able to do this with the necessary tenderness. You have to imagine something first in order to experience it, even when you smash right up against it. A man’s tenderness does exist in the same way as talking animals do. You can see it in their eyes. I do believe in the existence of tenderhearted men, I believe they’re everywhere, all around us, and animals that can speak intelligently to us of what they see and what their experience is. You just have to be able to understand the ways they communicate these things to us.

__________________________________

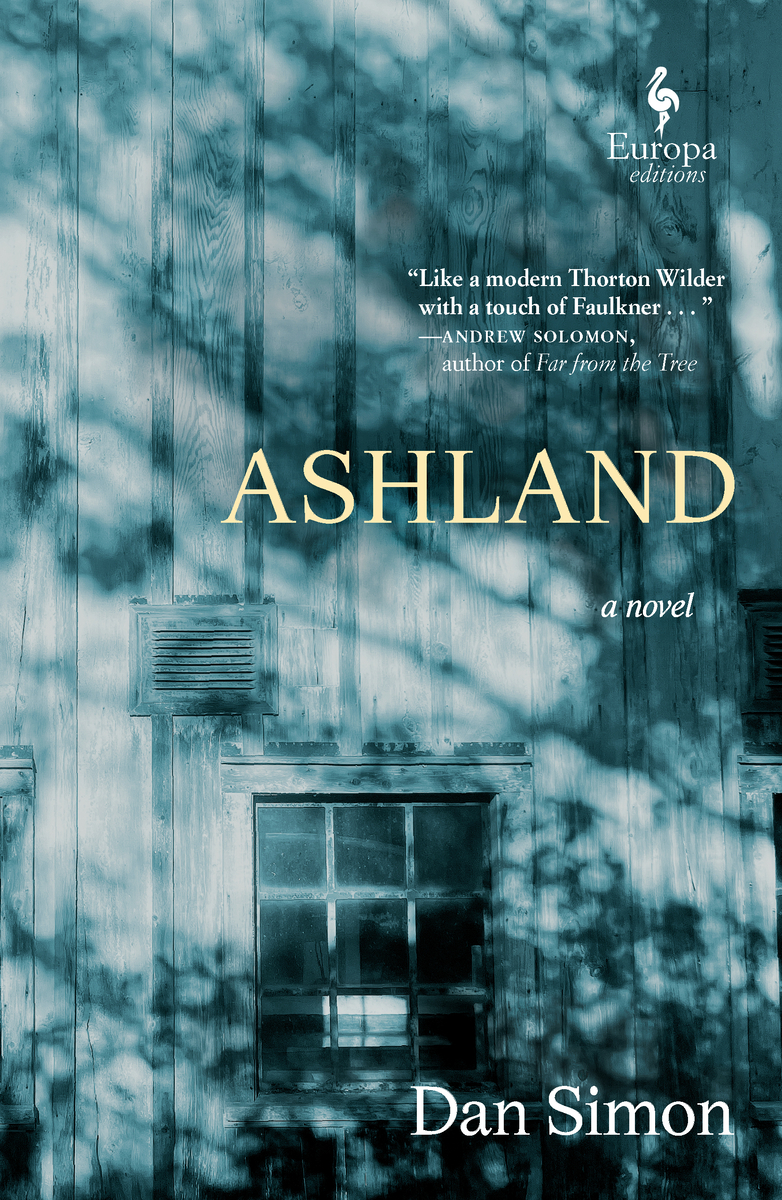

From Ashland by Dan Simon. Used with permission of the publisher, Europa Editions. Copyright © 2026 by Dan Simon.