Arthur Conan Doyle, Jack the Ripper and the Fact and Fiction of Criminal Profiling

Rachel Corbett on the Efforts to Find One of History’s Most Gruesome Serial Killers

Through the window of 26 Dorset Street, Arthur Conan Doyle took note of a chair, a bed, and a fireplace. The twelve-square-foot hovel, just off Whitechapel Road, was a “dismal hole,” as a friend with him that day put it, “somber and sinister.” Doyle was examining the scene for clues to an unsolved murder that had taken place in this room seventeen years earlier.

He replayed the sequence of events: Sometime after midnight on November 9, 1888, twenty-four-year-old Mary Jane Kelly entered the narrow, gaslit courtyard on the side of the house. She had been out drinking and perhaps meeting male clients. Right on the doorstep where Doyle now stood was the last place she was seen alive, alongside a young man wearing an overcoat and a felt hat. A witness later told police that Kelly invited the man in, telling him, “Come along, you will be comfortable.”

A neighbor reported hearing a woman scream around 3:30 AM. But she didn’t think much of it; fights were common in those parts.

The next morning, at 10:45, Kelly’s building manager knocked on her door to collect rent, which was six weeks overdue. No answer came. He went to the window, which had been previously broken during a fight between Kelly and her now-estranged husband, and pushed aside the rag covering it. There he saw a terrible scene.

A pool of blood on the floor; a smattering on the wall. Sheets of flesh piled on the table. And a body, or what was left of one, on the bed.

Sherlock Holmes and Jack the Ripper were in many ways perfect narrative foils: two murder-obsessed outsiders—one good, one evil—prowling the fringes of society.

He ran until he found a police inspector. “Another one,” he told him. “Jack the Ripper. Awful.”

*

Doyle was in his mid-forties and already the knighted author of the fanatically beloved Sherlock Holmes stories when he visited the East End that rainy spring day in 1905. He met up with his companions for the tour—an actor, a literary critic, a barrister, and a physician—at the Bishopsgate Police Hospital. They were all members of Our Society, a secretive gentlemen’s group that had recently formed to analyze the most gripping murders of the era and the criminal minds behind them. One of its members, Samuel Ingleby Oddie, had managed to secure an exclusive walking tour around each of Jack the Ripper’s five canonical murder sites, led by detectives and the police surgeon who had performed the autopsy on the fourth victim.

Oddie, who went on to become a coroner for the city, wrote in his memoir years later that of all the murders he’d seen, the one on Dorset Street was the most horrific. “I saw the police photographs of the mass of human flesh which had once been Mary Kelly, and let it suffice for me to say that in my twenty-seven years as a London Coroner I have seen many gruesome sights, but for sheer horror this surpasses anything I ever set eyes on.”

Our Society was popularly known as the Crimes Club and its members over the years included academics, the owner of the Daily Mail, and scores of writers, including P. G. Wodehouse and Bertram Fletcher Robinson. They gathered over dinner to discuss cases such as the serial poisoner Dr. Thomas Neill Cream; the “Brides in the Bath” killer George Joseph Smith, who drowned three of his wives; and now the infamous Jack the Ripper cold cases. They looked at crime-scene evidence, evaluated the police work, and considered whether the laws had been correctly applied. But they also took into account something the police often did not: the killer’s psychology. Fingerprints and blood tests were not yet available during Jack’s season of terror. But by the time the club formed, its members were learning about exciting developments in forensics, as well as a new field called criminology, which explored the root causes of and responses to criminal behavior.

Most members, including Doyle, had few reasons to visit the East End then. Home to around a million people, many of them Jewish and Irish immigrants, it was separated from the City of London by Whitechapel High Street. To the occasional West Londoner paying a visit, it felt almost like another country altogether, while many in the East End never went to West London at all. There were few opportunities for mixing in Victorian London. “There is no Prater, no Thiergarten, no Champs-Élysées,” a journalist wrote at the time. There was no central place “where all classes flock during the stifling heat of summer in a great city.” And one of the rare times they did meet was during the deadly 1887 class uprising in Trafalgar Square—a midpoint between the West and East Ends—where police beat working-class protesters in what became known as Bloody Sunday. So when news of the gruesome murders in the east reached residents in the west, many viewed the savagery as if it were happening in a distant land.

The Crimes Club members chose a particularly bustling day to visit the neighborhood. It was the eve of Passover and the area’s many Jewish residents had left their tenements and boarding houses to go shopping in such droves that Doyle couldn’t even free an arm to open his umbrella. The author delighted in the chaotic scene: wigged women clutching hens at the Petticoat Lane market, men herding cows through the streets and then dragging them squealing into slaughterhouses. Many of the locals worked in factories and slept in flophouses. The Shakespeare scholar on the tour, John Churton Collins, joked that even The Tempest’s disfigured slave Caliban “would have turned up his nose at this.”

Along the way, Doyle and his companions took note of the various escape routes at each murder site, all of them dark and private. The backyard of the lodging house on Hanbury Street, where Annie Chapman died, had three possible exits through neighboring yards; there were five at Mitre Square, where forty-six-year-old Catherine Eddowes bled out in a dark corner. That was only four hundred yards away from Berner Street, where the forty-four-year-old housekeeper Elizabeth Stride was killed just hours earlier. Stride’s throat had been slashed but she was left unmutilated, seemingly because a passerby interrupted the attack. Eddowes was not so lucky.

The police surgeon, Frederick Gordon Brown, coldly recounted the details to the group. In just eleven minutes, he explained, Jack the Ripper had cut out Eddowes’s kidney and uterus, as well as part of her colon. Next to her feet he arranged a few “presents”: a thimble, a comb, an empty mustard tin, and a coin. Police had found a bloodstained scrap of apron at the scene, which the killer may have used to wipe his hands. There was also a cryptic message written in chalk on a nearby wall: “The Juwes are the men that will not be blamed for nothing.” Its author was never identified.

The double murder raised the tally to four victims in a single month and plunged Scotland Yard into a panic. Robert Anderson, its chief of investigations, decided he needed to call for outside help. He wrote to Thomas Bond, one of London’s top forensic surgeons and a regular expert witness for the Crown, who was known for his opinionated testimony and calm temperament during some of the highest-profile murder trials of the day. Anderson asked whether Bond would consider examining the Ripper files and issuing a report.

Bond spent two weeks reviewing the detectives’ notes and forensic evidence from the murders of Polly Nichols, Chapman, Stride, and Eddowes. Then, in the midst of his research, a fifth woman—Mary Jane Kelly—was killed. When the police arrived at her home, they discovered a situation much like the others. Kelly, too, was a working-class woman living in Whitechapel. Her throat had also been carved open from ear to ear, and nearly all the way through. She’d been posed with her legs spread, slip pushed up to her waist, and she’d been gutted. Several organs, including her heart, were missing; her kidney and liver had been cut out and placed on the bed next to her.

But Kelly’s murder was even more gruesome than the previous four. She was the only victim Jack killed indoors, which gave him more time and privacy to do his butchery. Kelly’s face had been hacked so violently that her nose, ears, and eyebrows were missing entirely; so were her breasts. Her legs and forehead were skinned.

Bond performed the autopsy himself. Comparing the cases, he noticed that, in each, the first cut was to the throat, from left to right. The purpose of course was to kill, and possibly to prevent screaming, but the murderer’s true motivation was the mutilation that followed, leading Bond to conclude that all the women were killed by the same person. He probably used a large butcher or surgeon’s knife, at least six inches long.

The police surgeon who originally examined the body of the second victim, Annie Chapman, determined that “obviously the work was that of an expert—or one, at least, who had such knowledge of anatomical or pathological examinations as to be enabled to secure the pelvic organs with one sweep of the knife.” But with Kelly, the gashes to the face and body were crude and violent, nothing that suggested to Bond a skilled surgical hand. In fact, the stab wounds indicated that the killer had no understanding of anatomy whatsoever, not “even the technical knowledge of a butcher or horse slaughterer.”

Given that there were no indications of an accomplice, Bond predicted that the killer was physically strong and middle-aged. He likely had a “quiet, inoffensive” appearance, unlike the ghoulish caricatures printed in newspapers at the time, which would have made more memorable impressions on witnesses. Up to that point, Bond’s assessment was typical for medical examiners at the time. But he understood that Jack the Ripper wasn’t an ordinary killer. There was no discernible motive for the killings, which usually helped lead police to a suspect. So Bond did something different. He began to think beyond how the perpetrator killed his victims, to wonder why he killed them like this. What kind of a person would go to such extreme lengths to inflict bodily harm for no reason?

In what is now commonly considered the first known criminal profile, Bond put himself in Jack’s shoes to write his report. Jack would want to blend in, Bond reasoned, so he probably dressed respectably. A cloak or overcoat seemed a plausible choice for the nights of the murders, which would have the added benefit of hiding bloodstains on his clothes. As for Jack’s personality, Bond imagined it would take a man of “great coolness and daring” to grab a woman off the street, kill her before she could make a sound, and then excise her organs one by one, all out in the open for anyone to see. Clearly the killer had a methodical temperament, but he was undeniably also mad, and it was unlikely he would have been able to suppress that side of himself entirely. Therefore, he probably tried to avoid notice by remaining a “man of solitary habits,” Bond wrote, and earned a living through odd jobs rather than a steady occupation, for which he’d have to sustain relationships with other people.

Then there was the matter of motive. Bond considered the possibility that the killer was acting in the throes of religious fervor, or perhaps engaging in a revenge fantasy. But given the sexualized nature of the mutilations, it seemed most likely that Jack was afflicted with a case of “satyriasis,” a condition marked by uncontrollable sexual urges that, here, had manifested in periodic bouts of “homicidal and erotic mania,” Bond wrote.

Bond’s detailed predictions conflicted with those of other experts on the case. Other considerations included a doctor whose body was found in the Thames seven weeks after Kelly’s murder; a local Jewish barber who was known to hate women; a father who sought revenge against Kelly for supposedly giving his son syphilis; an unidentified midwife dubbed “Jill the Ripper”; and a thief who targeted prostitutes at knifepoint, known among locals as “Leather Apron.”

One Crimes Club member, Arthur Diósy, an expert in Japanese culture, suggested police look for a practitioner of black magic who killed women to source ingredients for an elixir of immortality. Another member, Oddie, believed the killer was probably an “insane medical man,” whose mania “culminated in the wild orgy of Dorset Street and was followed by his own suicide.”

The problem with all of these theories was that there was no evidence to support them. Britain’s police force was still relatively young and relied almost entirely on eyewitnesses, all of whose accounts, so far, had been uselessly vague. The frenzied press coverage of the murders further buried police in a flood of false tips. “The difficulty of our work,” one detective told a reporter at the time, “is much greater than the general public are aware of.”

Some officials blamed the community for its failure to catch the perpetrator. A few witnesses reported that Jack the Ripper had black hair and “foreign” features, reinforcing a popular belief in Scotland Yard that he was Jewish. But even though the police had knocked on every door in Whitechapel, none of its residents offered up a single suspect. It seemed impossible to Robert Anderson, Scotland Yard’s head of criminal investigations, that not one person living in the communal tenements had ever spotted a man acting erratically, or with bloodstains on his clothes. “It is a remarkable fact that people of that class in the East End will not give up one of their number to Gentile justice,” he wrote in his memoir.

“One did not need to be a Sherlock Holmes to discover that the criminal was a sexual maniac” and “that he and his people were low-class Jews.”

Anderson felt that Doyle and the Crimes Club criticized the police too much. He appreciated the underlying message in Doyle’s stories: “to think analytically…to think backward.” But it was not a lesson for police officers. “By none is it more needed than by those who fancy they need it least, our scientific experts and teachers of science,” Anderson wrote.

It’s worth remembering that it was the fiction writer Doyle—not Holmes—who tried to name the killer, and the real-life detective who covered it up.

But as the unsolved case languished year after year, it started to seem as though the police might need Sherlock Holmes after all. By the time Doyle and his club took their tour, some detectives hoped it might lead to a much-needed break in the case.

*

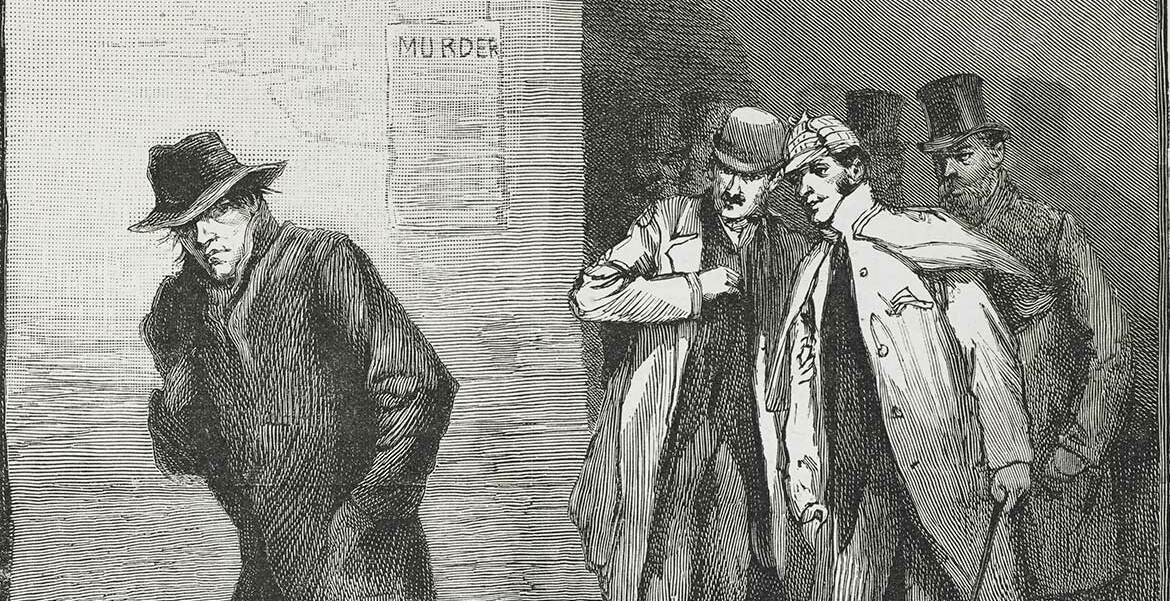

Sherlock Holmes and Jack the Ripper were in many ways perfect narrative foils: two murder-obsessed outsiders—one good, one evil—prowling the fringes of society. Illustrators even tended to portray them in a similar fashion: from the side, collars up, lurking in the shadows. Jack was identifiable by his signature top hat and knife; Holmes by his deerstalker cap and pipe.

The line between fiction and reality blurred when it came to Doyle, too, who had become synonymous with Holmes in the public imagination. Fans mailed letters to Holmes’s fictional address, 221B Baker Street, asking for help with various conundrums. And, to some extent, the figures merged in Doyle’s own mind: “A man cannot spin a character out of his own inner consciousness and make it really life-like unless he has some possibilities of that character within him.” As an ophthalmologist by training, Doyle shared with his amateur detective an exceptional sense of perception. And there were other parallels between the professions. Both detectives and doctors solve mysteries, starting with physical clues—forensic evidence or a patient’s symptoms—and then work backward to identify the cause. They tend to be calm under pressure, are trained in testing hypotheses, and are unfazed by blood and viscera.

*

In the more than 130 years since Jack’s murders took place they have been revisited by scores of armchair “Ripperologists,” who’ve offered up dozens of possible suspects. Among them are the artist Walter Sickert, who painted disturbingly accurate depictions of the crime scenes; author Lewis Carroll, who supposedly planted anagram confessions to the murders throughout his writings; Algernon Charles Swinburne, a poet of sadomasochistic motifs; and even Doyle himself—because who else could have invented such a thrilling, episodic murder mystery?

Scotland Yard commissioner Robert Anderson wrote in his memoir decades after the investigation that police had actually identified the culprit shortly after the murders took place, even before Doyle took his walking tour around Whitechapel. He explained that officers had sent an eyewitness—“the only person who ever had a good view of the murderer”—to visit the suspect, during which he was “unhesitantly” identified. “With his hands tied behind his back,” the man was later sent to a workhouse and then committed to an asylum.

Anderson gave only a vague explanation for why police never revealed the killer’s name: “No public benefit would result from such a course, and the traditions of my old department would suffer.” We may never know what those “traditions” were, or why they took precedence over the truth.

But in a roundabout way decades later, Anderson’s book did end up naming the likely suspect. The grandson of chief inspector Donald Swanson, a former colleague of Anderson’s, found an old copy of the book in the 1980s. In the margins, Swanson had written: “Kosminski was the suspect.”

Today, many analysts agree that the killer likely was Aaron Kosminski, then a twenty-three-year-old Jewish barber from Poland who moved to Whitechapel in the early 1880s. Scotland Yard’s assistant commissioner, Melville Macnaghten, wrote in an internal memo that Kosminski, who was on the official list of suspects, “became insane owing to many years indulgence in solitary vices,” which apparently meant masturbation. “He had a great hatred of women, especially of the prostitute class, and had strong homicidal tendencies.” He also reportedly heard voices and once threatened his sister with a knife. He died in an asylum in 1919, at the age of fifty-three.

In recent years, biochemists examined a silk shawl that was said to have been found next to Eddowes’s body, and which a Ripperologist bought at auction in 2007. They found fragments of DNA on it that matched descendants of both Eddowes and Kosminski. Still, many experts believe that mitochondrial DNA matches are insufficient to prove a suspect’s guilt, and that not enough of the sequences were published to enable a judgment.

In the end it turned out that Doyle’s detective work, like much of Lombroso’s criminology, was better suited for fiction. The killer apparently wasn’t a medical expert, and the “Dear Boss” letter that Doyle had examined turned out to be a hoax, written by a young Canadian woman living in England. She was convicted after investigators discovered copies of the letter in her home.

But perhaps a convincing narrative is what the public needed the most then. The flourishing penny press that had made Jack the Ripper a celebrity ran relentless reminders of the murders. Papers speculated endlessly about his identity, even when there was no new information to report. Perhaps Doyle’s calm, rational detective, who always prevailed in the face of madness, was a solace for the times. But it’s worth remembering that it was the fiction writer Doyle—not Holmes—who tried to name the killer, and the real-life detective who covered it up.

__________________________________

Adapted from The Monsters We Make: Murder, Obsession, and the Rise of Criminal Profiling by Rachel Corbett. Copyright © 2025 by Rachel Corbett. Used with permission of the publisher, W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. All rights reserved.

Rachel Corbett

Rachel Corbett is the author of You Must Change Your Life, which won the Marfield Prize, the National Award for Arts Writing. She is a features writer at New York magazine, her writing has appeared in The New Yorker, New York Times Magazine, and The Atlantic. She lives in Brooklyn, New York.