Art Spiegelman: If It Walks Like a Fascist…

On Nazis, Despair, and the Genius of Si Lewen

Like millions of Americans, I’ve spent the past year or so, and the past few months especially, in a state of semi-constant dread. Hard as it is to believe, the host of Celebrity Apprentice is our president. Donald Trump, who led the nakedly racist birther movement, has replaced the very man whose legitimacy he once questioned. His inner circle is meanwhile filled with white nationalists, religious ideologues, and cruel embodiments of our corporate state—men and women set on protecting big business from American citizens.

To defend us against this predatory regime, we’re asked to count on the “resistance” of the Democratic Party—the same party that under Bill Clinton oversaw the deregulation of Wall Street, the gutting of welfare, and the doubling of our federal prison population; that under George W. Bush gave its green light to invade Iraq; and that under Obama embraced both mass surveillance and extrajudicial drone warfare.

For all these reasons, I’m increasingly unconvinced by our self-proclaimed “voices of reason.” People like Barack Obama after all assured us that Trump could never win the presidency. Now they maintain that our democracy still has robust checks and balances; that Trump’s reign will be a mere comma, not a period, in American history. Perhaps they’re right, or perhaps they underestimate the tides into which we’ve just been swept.

*

In these dystopian times, I find myself turning not to politicians and journalists for guidance, but to our most paranoid writers and artists—those whose tone seems suddenly suited to our new reality. One such artist is Art Spiegelman, the cartoonist best known for his graphic memoir Maus. The baseline dread that runs through so much of his work no longer strikes me as neurotic, but, alas, as clear-eyed and prescient. For whether portraying his parents’ experience as Polish Jews in Auschwitz or commenting on September 11th and its aftermath, Spiegelman invariably exposes our false sense of security—our conviction that history’s darkest chapters won’t repeat themselves, not with us as the protagonists.

This belief—call it rational pessimism—is understandable given Spiegelman’s childhood. As readers of Maus will recall, he was raised not just by Holocaust survivors, but in the shadow of a sibling whose young life was claimed by Hitler. Richieu Spiegelman, six years Art’s senior, had been sent to live with his Aunt Tosha during World War II, in a ghetto where his odds of survival were slightly better. But even there Germans eventually rounded up the Jews for Auschwitz, leading Tosha to make an unimaginably difficult decision. Before being captured, she decided to poison herself, along with Richieu and the other children in her care—all to avoid descent into the death camps. This was the family story into which Spiegelman was born in 1948.

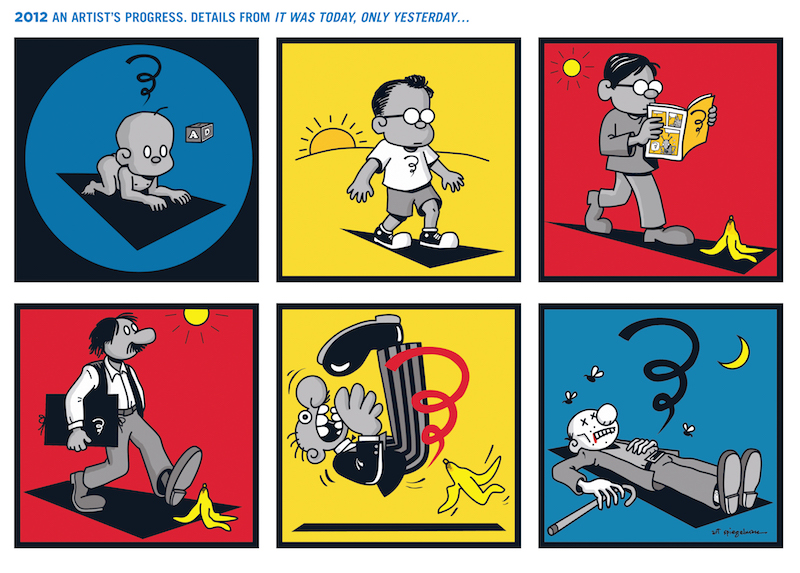

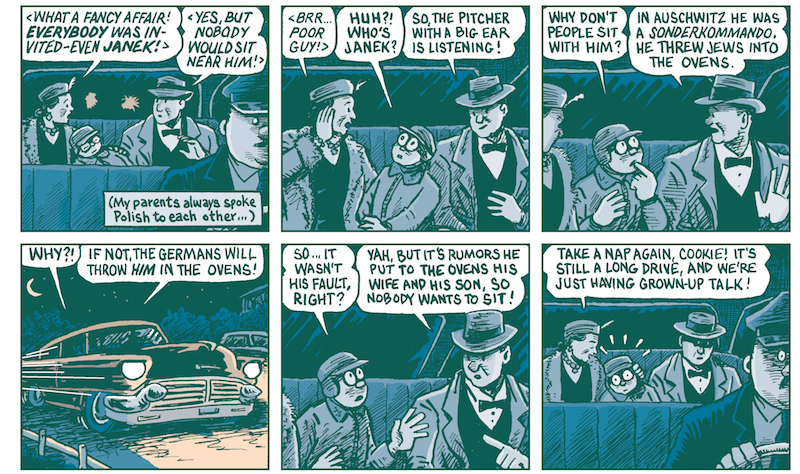

From Portrait of the Artist as a Young %@&*! (2008)

From Portrait of the Artist as a Young %@&*! (2008)

The Holocaust’s shadow darkened Spiegelman’s nascent worldview, and it drew him, in its strange way, to the pages of MAD magazine. Unlike the 1950s culture it satirized, MAD made clear that authority figures are full of shit; that those in power—who’d have us believe everything is chugging along just fine—are, as they always have been, either deluded or lying. By Spiegelman’s account, MAD did more to shape him than any other influence. In fact it led him on a path toward underground comics, where eventually, inspired by friends and mentors like R. Crumb, he portrayed the world as he saw and, even more so, as he felt it—always teetering, behind its sleek façade, on the edge of barbarity.

The strip “New York Journal: “Spiegelman moves to N.Y. ‘Feels Depressed!!!’” captures that psychic atmosphere. In the span of its single page, Spiegelman’s cartoon avatar does the following: squash cockroaches in his infested apartment; go to the Museum of Modern Art and fail to meet women; head out to a meeting and then to a depressing strip club; kill more roaches at his apartment; attend a cocktail party, where he doesn’t know what to do with himself; go back home to read a book called Before the Deluge, about Berlin in the years leading up to World War II; and then contemplate whether to jump off the roof of a nearby hotel or, perhaps, start seeing a shrink like all his friends.

For Spiegeleman—who was briefly institutionalized as a young man, and whose mother committed suicide soon thereafter—we, as a species and as individuals, are always living both before and after a deluge.

*

Throughout the 1980s, Spiegelman collaborated with his wife Francoise Mouly on RAW, the paradigm-shifting comics magazine they co-edited. He also worked on an ambitious new project—a history and memoir of his family’s experience in World War II. Maus, which took him six years to write, is about his parents in the years leading up to their capture and transfer to Auschwitz. But it is also, and perhaps especially, about Art Spigelman, their chain-smoking, good-for-nothing son; the would-be artist who schleps out to Rego Park, Queens to interview his dad about the war, to gather material for his comic book and engage in tedious arguments over trivial matters. By foregrounding this father-son dynamic, Spiegelman highlights both his own selfish desires and his father’s many flaws. In so doing, he resists the common urge to equate suffering with virtue. He reminds us that Holocaust survivors and their children are no better than anyone else; they are human, with all the complexity that entails.

Though its cast of characters consists of mice and cats (Jews and Germans respectively), Maus nonetheless managed to pioneer a convincing new form of realism. At a time before people referred to such books as “graphic novels,” it demonstrated that comics can indeed cover the same emotional range as novels. Almost single-handedly, it ushered comics into the respectable mainstream, inspiring generations of new artists—people like Marjane Satrapi—to tell their own stories in that format.

In 1991, five years after the release of Maus, Spiegelman published its sequel, which covers the time his parents spent in Auschwitz. Maus II also shows him as he copes with the success of his first volume, wrestling with the complex guilt it brought forth. In one spread, Spiegelman sits at his drafting table, listing various seemingly disparate facts for his reader. He mentions deaths in the Holocaust, the deaths of his parents, the birth of his child, and the success of his book. Sprawled at his feet, dozens of bodies resemble both the dead at Auschwitz and a pile of discarded draft pages. As the art critic Robert Storr wrote about that image, “this is not a sick joke but evidence of the heartsickness that motivates and pervades the book; it is the gallows humor of a generation that has not faced annihilation but believes utterly in its past reality and future possibility.”

From Maus II: A Survivor’s Tale: And Here My Troubles Began (1991)

From Maus II: A Survivor’s Tale: And Here My Troubles Began (1991)

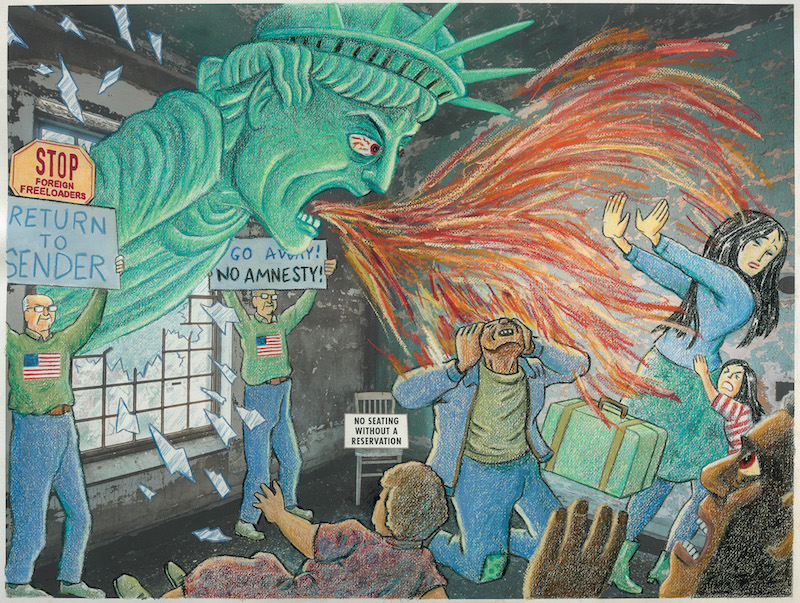

In the years following Maus II, Spiegelman drew a number of covers for the New Yorker, where Francoise Mouly was and still is the art editor. All the while, he continued to occasionally publish short comics, many of them focusing on his obsessions and fears—on the capacity of men to do horrible things to one another. In 1992, for instance, he drew up his visit to Rostock, where a building of Roma asylum-seekers had just been firebombed by skinheads. More recently, in 2009, he reflected on the voyage of the St. Louis—a boat of Jewish refugees fleeing Nazi Germany in 1939. All 900 passengers were denied entry on our shores, and forced to return to Europe on the eve of World War II.

In re-telling that dark episode from our past, Spiegelman explores how the news was covered by American cartoonists, only a few of whom realized its import. Not that we have any standing to get on some high horse about it. “Lady liberty still has plenty to answer for,” Spiegelman writes, as the Statue of Liberty distributes jumpsuits and handcuffs to refugees. A caption explains: “I just read a new report from Human Rights First online. Since 2003 over 48,000 men and women who have fled to America to escape political, religious, or ethnic persecution have been detained by the department of Homeland Security in harsh prison-like facilities for months, even years, often without an immigration court review.”

*

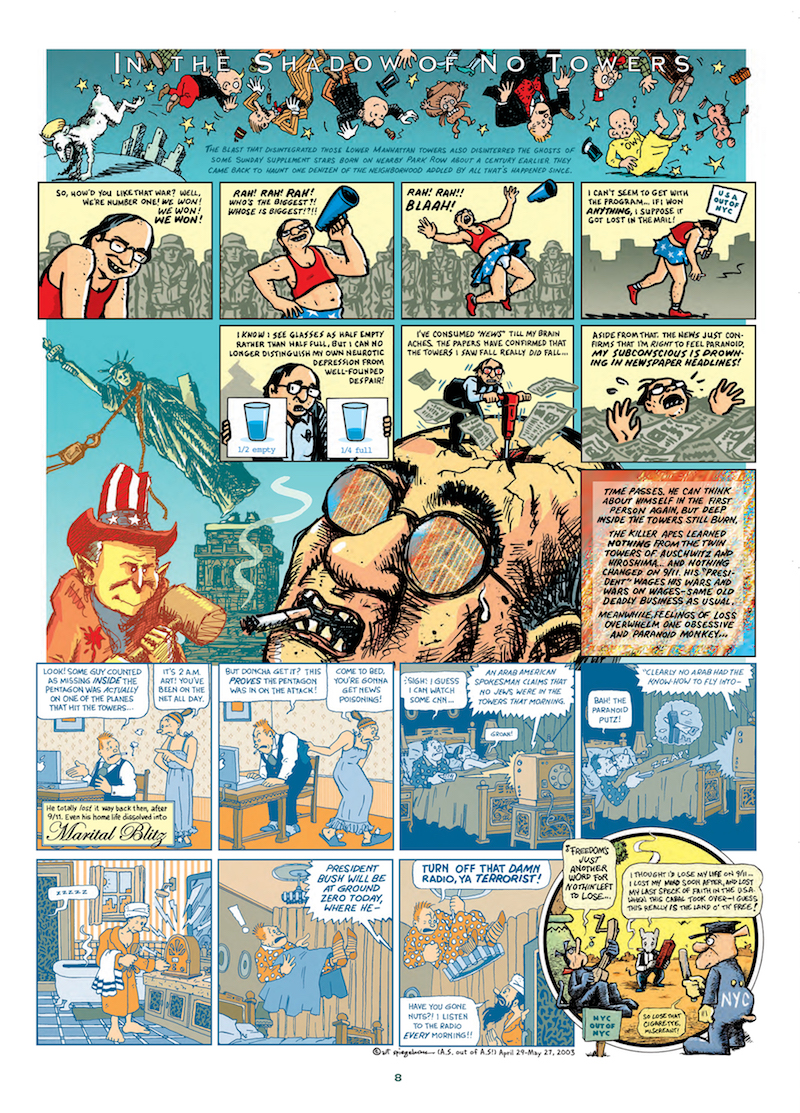

Eight years earlier Spiegelman had witnessed the 9/11 attacks first hand. Having just dropped off his daughter at her downtown school, he watched from the sidewalk as both towers burned and crumbled to the ground. His sense of safety and security were shattered in that instant. More than that, he was horrified by his government’s exploitation of the tragedy, by their use of it as a pretext to erode our civil liberties and wage war. To explore his resulting flood of emotions—paranoia commingled with anger, fear, despair, and guilt—Spiegelman got to work on dense and messy comic spreads. The cartoons he published—first in newspapers, then as the 2004 collection In the Shadow of No Tower—have more in common with the rants of stand-up comics than the measured arguments of essayists.

In one memorable spread, he portrays his brief flirtation with network television, which invites him to participate in a one-year anniversary of 9/11. With cameras rolling, Spiegelman is asked to name the greatest thing about this country. “The greatest thing,” he says, just before being kicked out to the curb, “is… uh, that as long as you’re not an Arab you’re allowed to think America’s not always so great!”

From In the Shadow of No Towers (2004)

From In the Shadow of No Towers (2004)

A similar defiance characterizes his 2015 collaboration with the photographer JR. His task for that project was open-ended: draw whatever you want about Ellis Island and its abandoned hospital. Rather than look to the past, Spiegelman focused his eye on the present, on the hatred he felt bursting through the seams of Obama’s America. He drew an image that in its way foresaw the rise of Donald Trump. It portrays the Statue of Liberty, eyes bloodshot, bursting through the Ellis Island hospital window—spitting fire at a crowd of immigrants, women and children among them. Behind her, watching the carnage from a safe distance, two bland enough white guys—balding, gray-haired, and in matching American flag sweaters—hold up signs that read: “Return to Sender” and “Go Away! No Amnesty!”

From The Ghosts of Ellis Island: A Project by JR with Drawings by Art Spiegelman (2015)

From The Ghosts of Ellis Island: A Project by JR with Drawings by Art Spiegelman (2015)

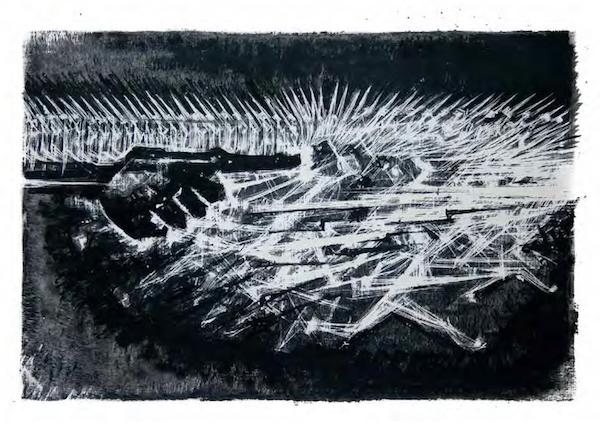

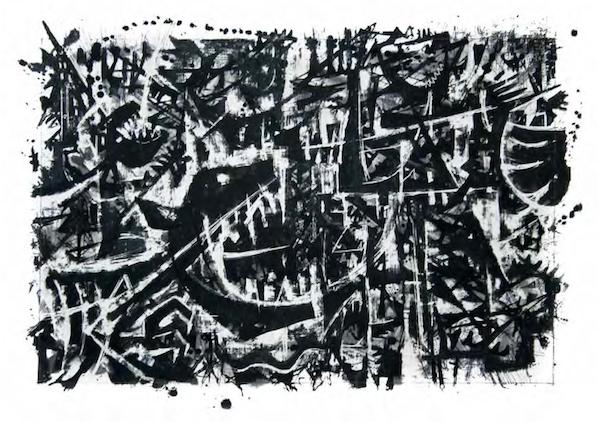

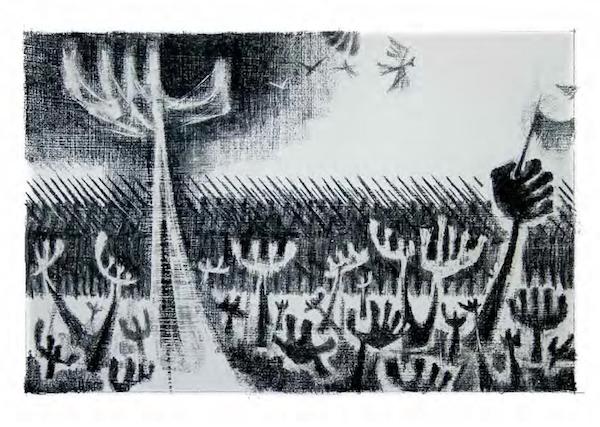

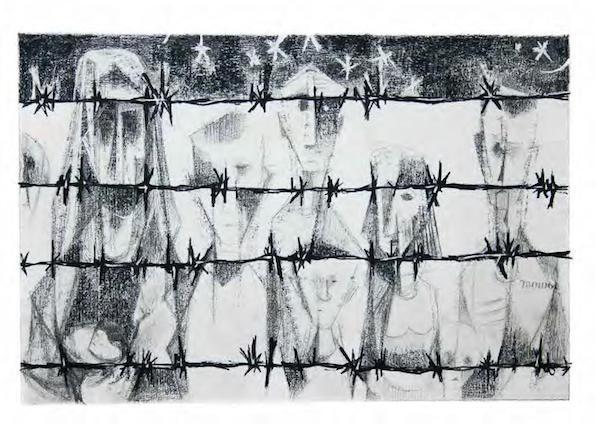

In parallel with these projects, Spiegelman spent much of the past decade delivering a lecture called “Wordless!” which lays out the history of what we now call graphic novels. As part of his research, he one day stumbled on a forgotten book from the 1950s. The Parade, by the American artist Si Lewen, portrays a population drummed into a collective and patriotic frenzy. Set in an undefined place and time, unfolding in stark and expressive black and white, it exposes the ugly sadism of war—of those times when men are freed from even the pretense of civilization.

From “The Parade,” 1957, from Si Lewen’s Parade: An Artist’s Odyssey (2016)

Spiegelman was blown away by what he saw, and he sought to include images from The Parade in “Wordless!” He reached out to Si Lewen, who by that point was in his nineties, living in a nursing home, and still painting on a daily basis. You can use my images, the artist said, but I refuse to be paid for them. By way of explanation, he told Spiegelman the same thing he told the commercial art world in 1985, when he left behind what had been a financially successful career. Then and now, Lewen proclaimed: “Art is not a commodity! Art is priceless!”

The artists struck up a friendship soon after that first exchange. Spiegelman even offered to oversee the re-release of Lewen’s work, which led to the publication, a few months ago, of Si Lewen’s Parade. The book’s accordion format allows readers to view the “wordless novel” as an uninterrupted stretch of images, just as Lewen first intended. And when flipped, it tells the story of his long and eventful life.

Si Lewen was born in Lublin, Poland in 1918. Two years later, his family moved to Berlin, hoping to avoid Polish antisemitism. They soon discovered its German analogue, needless to say, and Lewen was taunted by classmates as “that Polish Jewboy.” When Hitler won the Chancellorship in 1933, the hardheaded 15-year-old made up his mind—despite his parents’ objections—to flee for France. It was only through a series of lucky breaks that the family eventually reunited, when a few years later they earned immigration visas to America.

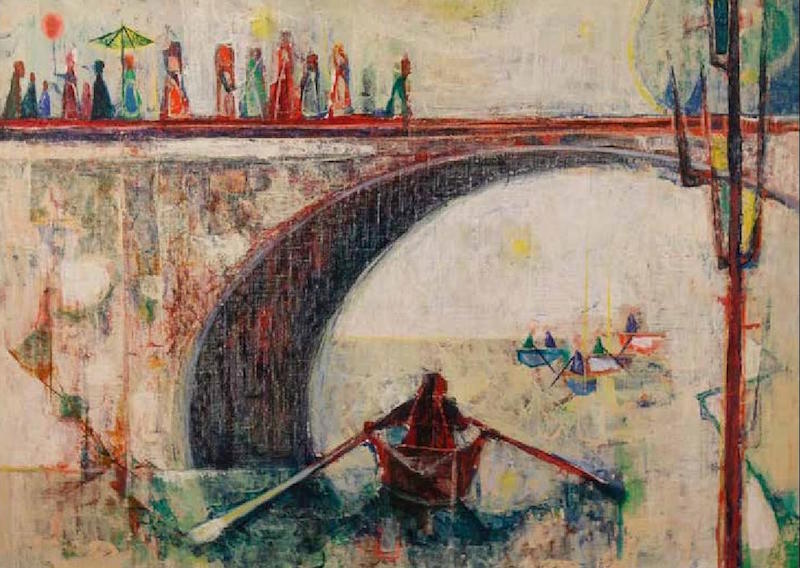

In 1936, early into his new life in New York, Lewen was stopped by a police officer in Central Park. The cop demanded to see his papers, and Lewen complied, explaining that he was a Jewish refugee from Europe. He figured the officer would sympathize with a living embodiment of Hitler’s victims. But instead, the man called Lewen a “Jew bastard”; he ordered him onto a boat and proceeded to beat him senseless. The resulting trauma led to a suicide attempt, which in turn landed Lewen in a mental hospital. Even after his discharge, the episode remained in the background of his work—not just in The Parade, but also in paintings like “Sunday Bridge,” where a boat glides on kaleidoscopic waters. In Lewen’s universe, even that idyllic scene confronts us with the violence of our species—a violence all the more horrifying when obscured by shimmering beauty.

“Sunday Bridge,” 1952, from Si Lewen’s Parade: An Artist’s Odyssey (2016)

“Sunday Bridge,” 1952, from Si Lewen’s Parade: An Artist’s Odyssey (2016)

In 1942, Lewen joined the American army. Though an avowed pacifist, he was willing to make an exception for his childhood tormenters. After Germany’s defeat, he was among the first Americans to liberate the Buchenwald camp. What he found there was first-hand evidence—undeniable proof—that men are not just capable of descending into animalistic madness, but programmed to do so when offered the chance. As he later wrote,

My insides were one wrenching mess. I knew that I was finished as a soldier, seeing the world for what, I thought, it was: a slaughterhouse, a bordello, and an insane asylum, run by butchers, pimps, and madmen. And Man? A festering, putrid, slimy excretion polluting the face of the Earth. A hospital ship brought me back to America, and half a year later I was discharged—“as good as new,” one of the doctors said. I was not so sure.

This feeling—that “the ultimate horror of the Holocaust may be that it was all too human”—is one Lewen went on to dramatize in The Parade, a work praised by all who saw it, including Albert Einstein. “Nothing can equal the psychological effect of real art—neither factual descriptions nor intellectual discussion,” the physicist wrote. He then concluded—this was in 1951—that “our time needs you and your work!”

*

In his last years, after nearly a century of painting daily, Lewen grew plagued by the symptoms of his arthritis. The pain was in fact so bad that one day he tried and failed to saw off his hand, scrawling the word “enough” in blood on his studio wall before collapsing. Once he recovered, Lewen embarked on a new phase of artistic creation. He molded sculptures of gnarly, expressionistic white hands, which he installed along the floor of his studio. As Spiegelman writes in Si Lewen’s Parade, “it looked like a zombie apocalypse!”

“Hands,” 2014, both from Si Lewen’s Parade: An Artist’s Odyssey (2016)

“Hands,” 2014, both from Si Lewen’s Parade: An Artist’s Odyssey (2016)

In the run up to the book’s publication, Lewen asked Spiegelman if he planned to tell the truth about his injury. Yes, the cartoonist replied, I’ll have to be honest. “But hey,” Spiegelman added, “it worked for Van Gogh—did wonders for his career!” And who knows, maybe one day keychains and other trinkets will be shaped like Lewen’s hands. Maybe Spiegelman’s book marks the first step in a long rehabilitation. Or maybe Lewen, like so many others, will soon fade into oblivion.

The media’s reaction to his death is in any case instructive. Lewen died on July 25, 2016—a few weeks before the release of his book and a few months before the election of Donald Trump. The New York Times chose not to print an obituary. The editors had apparently concluded that the only notable fact about Si Lewen is Art Spiegelman’s affection for his work.

*

Because I disagree with them—because I think Si Lewen is well worth remembering—I recently reached out to Spiegelman for an interview. This was shortly after Trump’s victory, a month or so before the inauguration, and I wanted to know what he made of our country’s latest turn for the worse. I wanted to know what he made of Donald Trump in light of Si Lewen. Spiegelman obliged, speaking as he always does at machine gun pace—like a man with too much to say and too little time to say it.

AA: I’m curious to hear what you make of Trump’s election, especially in light of your recent work with Si Lewen.

AS: Well, the world has so much going on in it right now, so even though this book is germane, it’s a very disorienting moment… Actually I discovered what they’re calling the alt-right last night. I’d vowed not to draw Trump during the entire last year, because I felt that everything was fuel for that fire, that there’s no such thing as negative attention for a narcissist. But now that it’s entered so deeply into the world, and into me, I have to do it. So I was looking at pictures of Trump, and there’s one that I pushed a close-up on so I could see how his profile works, and then all of a sudden, there I am, on some site called Stormtrooper. It was impressive, because it has the same snark as the rest of the Internet, but with an absolutely murderous agenda.

AA: That’s a dangerous rabbit hole to go down…

AS: This was all the way out. I didn’t follow it exactly, but the punch line was “kill the Jews,” basically, when you get right down to it. I don’t think this is paranoid when we talk about Trump; I think it’s just… observing.

It’s one of the things, when we looked at Si Lewen’s life—he’s 15 years old, he just saw Hitler come to power, 1933, and he’s outta there. He can’t convince his parents, so he takes his 16-year-old brother—he says, you should leave also, you’re crazy to stay, we’re getting out of here. And they left for France, because they saw, somehow—they felt viscerally what was coming. I don’t think there’s anything about Trump that I need to know beyond what I know already to know that it would be smart to leave. I’m just too settled in my ways to go to Canada with the rest of the fantasyland world, looking for the universe next door that we should be living in.

AA: Part of why I wanted to talk to you is because I feel, looking back at your 9/11 cartoons, that at the time you were experiencing a kind of manic paranoia. And in fact you were right to feel that way, even as others carried on with their normal lives. I’m reminded of that now with Trump coming to power, as people seem desperate to convince themselves that, yes, the man is horrifying, but we’re going to make it through.

AS: So-called normalizing…

AA: Even more than normalizing. It’s a form of denial—or a desire people have to be optimistic.

AS: Well, I think just enough time has passed so the Holocaust is now a story. And stories are… interesting. But it doesn’t feel as visceral for most people. You know, I have it built into my epigenetic DNA to be nervous and know that the sky is falling, so if anything, I would move further in that direction. But it did seem that, clearly—and it’s still clear now—9/11 was an important inflection point in the change of what has happened and is happening to us now—the absolute xenophobia that has come up with it—all of those things are very specifically there, with this crazy interesting plot twist of having our first and last black president.

AA: Who could make that up?

AS: Who could make any of this up! If I was just able to be from the universe next door and peek into this one rather than vice-versa, I would go: it’s [the work of] a great novelist! You know? You couldn’t believe that all of these threads actually keep echoing with each other. But there it is. I think the alt-right has to do with the fact that I’m really living in that alternate universe next door. It’s a clue that this is one of the worst dreams I’ve ever had. “Alt-right” is an odd phrase—“alt” is old in German right?

In any case, the fact is that the alt-right has opted—that faction of the right that I was looking at last night has opted—to use all of the strategies of MAD comics in the 1950s. MAD was able to combat the deadening media of the 1950s—by deconstructing it, by twisting it with irony. And that’s the conscious strategy of at least this website I went to last night—to be attractive to nihilistic teens.

AA: It’s a conscious strategy of the alt-right, and on some level of Trump himself…

AS: Well, we now have a short attention span consciousness—because of all the stuff that came with this relatively recent invention that just ran out of batteries before you and I talked—the portal to the universe. It doesn’t encourage digging in and thinking something through. It’s how we got to this place where—what are they calling it now—a “post-fact culture”? You get to choose whatever bubble you want to live in. I’m sure I’ve chosen mine as well, and within that you put every other bit of—in quotes—“information”—in a constellation around that. So Trump understands that in the same way that, from what I remember reading back in the day, Kennedy understood television. He’s a creature of that.

AA: Did you ever talk to Si Lewen about Trump?

AS: Not about Trump—it was hard to take him seriously. But I did ask Si if he was for Bernie or Hillary, which seemed like the choice at that time. He said Hillary, because he believes deeply in the matriarchy. It’s the first words of The Parade. The dedication is “to our children,” and it deals with a mother, horrified, having to let her boy go into the war fever that consumes them. And it ends with a mother hugging a child while the dogs of war continue to howl for the next round of destruction. It’s the essence of that book, and for what he felt was the male project—that it wasn’t grounded in keeping children alive. He wanted a matriarchy.

AA: Do you think he would be as despairing as you are now?

AS: Like I said, he had his early radar warning out in such a way that as a 15-year-old kid he left his family and just moved to France, not knowing what that would mean. He just went across the border and ended up working on farms and things like that. That’s a big move! You’re 15 years old, you’re in the cradle of an intelligent family, and you flee—and you tell them they should be fleeing too? He knows what these people are. It’s right after Hitler came to power. So to answer your question: yes. I don’t think Si would be able to put this in some perspective that would make anybody feel better.

AA: What was it about The Parade that first caught your attention?

AS: I guess that it was not an ironic work. It was made during the period of modernism, let’s say, but on the other hand it didn’t seem kitsch. You know, I think I coined this phrase “holo-kitsch” when I first saw Life is Beautiful—which, by the way, I was horrified to find had been inspired by Maus, and if I could go back in time, one of the many things I would do, as well as assassinating Hitler, would be plucking that book out of Roberto Benigni’s hands at a crucial moment.

But yes, Si’s work was emotional and convinced, and convincing, without being kitschy. That really knocked me out, that it’s such a universal story. It doesn’t feel contrived, it feels just like a very pure wail of poem or song. It didn’t bother with the narrative complications that would make the story a really specific one, and it really got to the heart of something that one can do with pictures, which is tell something that can resonate across language and cultures and be such a basic thing—which is… we’re just watching this cycle, and as we dip towards more and more conflagrations, this becomes a compass.

AA: Do you think we’re in it now—the cycle portrayed in The Parade?

AS: Well, I’m afraid so. A lot of The Parade uses as its metaphor the feverish seduction of the group mind, right? The parade: everybody getting in line to go off a cliff. And that’s all I can see as this thing happens—as we’re told that, you know, about half your countrymen are already lined up, so get in line.

AA: And it’s easy to forget that half the population was horrified whenever these same forces emerged throughout history. It’s not that everyone needs to fall in line, necessarily—it’s just that the people who don’t fall in line need to be powerless.

AS: That’s what scares me at the moment, there’s so little place to hang on. We’re back to, like I said, a very flawed system indeed, but where all of it is tipped into one half of the scales. Boy oh boy, there’s hell to pay. And the fact that it’s international means that it’s not just our bubble. It’s the western civilization bubble.

AA: Plus the people now in charge seem genuinely uninterested in this country’s history, or uninterested in it outside of some gross mythology…

AS: Yes, “making America great again” consisted at one of time of giving typhoid-filled blankets to Indians to keep them warm… and now trying to mow them down as they try to protect whatever little scrap of earth they’re still standing on. It’s quite something to be able to talk about how it should be great again. Like, meaning what? Northwest European in its roots, and everything else has to go?

But what I’m trying to look at with Si is how he was able to keep joyous things in his work. There are some parts of them that have a joyous sexual energy, you know? And that kept him going.

AA: There’s a line that stood out to me from Si Lewen’s Parade. He’s talking about the Cold War, about the nuclear threat that came up after World War II: “Try as I might, I could not keep pretending I did not see what I saw. In almost schizophrenic confusion I tried to expunge my vision of a horror-filled past by ever-more light-filled paintings while at the same time pursuing that very same nightmare-filled vision.” Do you think he was ever able to escape that dread, or to work without it?

AS: I think he had to enfold it, you know? I’m finding more and more that I’m really interested in Sam Beckett. I just keep returning to him as some kind of bedrock—“can’t go on, must go on, will go on.” Godot is called a tragicomedy, and I’ve been thinking about that word a lot, because it doesn’t mean tragedy and then comedy; it’s trying to conflate them into being one word, so that these things are simultaneous. Looked at one way, from an Olympian point of view, it’s hilarious! And from another point of view, it’s an absolute tragedy, with all of the depths of meaning that that has.

And that simultaneity, I think, is what I was hearing in Si as well. His work was so thoroughly informed by the pain that he lived through, having been so close to the heart of the darkness of the first half of the 20th century. That kept him sensitive to the darknesses that were coming along. At some point he even took his wife on a vacation to Hiroshima, because he had to understand what had happened there. But at the same time, he was able to make paintings that, you know—some of them really were kind of funny, and a number of them, like I say, were there for their psychedelic beauty.

I think in some ways, despite the things that he went through personally, that give him an authority to speak—I feel that in some ways I wear bleaker glasses than Si does.

AA: Do you feel any agency in this moment?

AS: Well, it’s all so out of whack, and it’s so big. That’s why what comes to my mind at this point is: we don’t have a lever of government to work with, but we have to resist this thing, and we’ll figure out what resistance means the same way as little bands of people living in forests in Europe, trying to figure out what they could do.

But I have to keep using this metaphor of the universe next door, because what I read somewhere outside of science-fiction is that they all exist, all these universes, and there’s one that makes a lot more sense than the one we’re freefalling through right now. Isn’t it terrible? Like, there’s no way to talk about anything but this. It’s hard to get one’s brain around it.

AA: I guess if we’re always imagining the different scenarios that might play themselves out, the prospects going forward just got a whole lot worse. All roads now seem to lead to either a minor or total apocalypse…

AS: I’ve got to say, as long as we’re talking about the election, that I didn’t feel that Hillary was going to save us either. It’s just that she’d keep things a little bit more rational as we tried to fight our way through. But her inclination toward hawkishness, reading about her input in the last administration, didn’t seem like a great way to survive. That’s why I say, this is so big. Reading about the far right wing and the further right wing in France doesn’t make me believe that there’s anything to accept, or that one can get purchase to move things away and postpone some kind of absolutely terrifying endgame—to quote another Beckett title.

AA: Have you drawn anything yet relating to this mess?

AS: Just making notes over the past few days. I have notions, but I don’t know where they are yet. As I’m settling in now, I feel like I’m aimed at a grind table. I have to be in order figure out what’s happening to me.

AA: Before this call, I was looking back at Breakdowns, your first book. It was interesting to see how many of those comics express your nightmare visions—you know, dreaming about being in a bathroom stall and this mob comes in, out for the blood of homosexuals; or one of your fingers comes to life and starts screaming “JEW!” Were you exorcising demons on some level—drawing those fears so they wouldn’t become reality?

AS: No… I mean, I’ve always been exorcising demons, but there are demons. There just are. So what I was doing was trying to take a reading. You make the work in order to find out what’s around you, and I was just epigenetically, if that can be said, programmed to see the worst by seeing what my parents had come through. It’s just part of the lens. You know, there’s a quote from Philip K. Dick that says something like, “reality is what won’t go away when you choose not to believe in it.” It’s crazy that Philip K. Dick should be the real avatar of science fiction now, instead of the more nostalgically tinted Ray Bradbury, or the more technologically focused Isaac Asimov of my youth. Philip K. Dick seems to have nailed it. Those kinds of things seem uncannily prescient.

AA: It’s discomforting to realize that the people who had it right were also those who went kind of nuts…

AS: I remember my mother warning me away from thinking too hard about the Holocaust, or about knowing myself. My mother had said, when I was younger, don’t write about this, because people who write about the Holocaust end up killing themselves. That was before Primo Levi. There is always that danger. But it is kind of amazing what artists’ antennas can find, and I think Philip K. Dick, who was a touchstone for me, just seems to be so clear-eyed.

AA: It makes you wonder if one of the markers of being civilized—or of being perceived as civilized by the common denominator you’re interacting with—is having enough of an ability to deny that the train’s going to crash.

AS: Yes, denial is part of our survival mechanisms. People going to sleep in Auschwitz dreaming of meals they’d had…

AA: Maybe there’s some wisdom in that. It’s not like it’ll make a difference one way or another that I’m playing out dystopian scenarios in my mind.

AS: Well, if more people, since we’re using mainly the World War II paradigm, if more people took Hitler seriously when he was seen as a useful buffoon… it would be unnerving to have to deal with that, but it probably would have been useful for more people to keep their eye on the ball. One does what one can. And you have to leave room for pleasure. That’s one of the themes I’ve been coming back to as we talk about Si’s work, is, you know, the work wasn’t all the bleakest, darkest, Otto Dix, George Grosz reality—even though that’s a strong aspect of what struck a responsive chord for him. It was bigger than that. It’s important to find reasons to want to keep going, rather than saying, let’s blow the whole damn thing up and see the universe start over, this was just a mistake. One does what one has to do, but that has to include some degree of… finding the people and things one appreciates and loves… I’m trying to keep those things in a mix, rather than just saying, “the sky is falling, the sky is falling, the sky is falling.”

AA: Are you better equipped to survive this—mentally, I mean—than you would have been had Trump come to power in the 1970s, when you published Breakdowns?

AS: Well, you know, I was making those comics in the midst of the Vietnam War; and then making others when Reagan came to power. And then, oh my God, there was the Iraq War… These threats are always there, but they do seem to somehow get larger, not just because they’re foreshortened and closer in time. Reagan now looks like an august statesman to me. Like I was saying earlier, if one could just look at it with enough Olympian distance, it’s one hell of a tale. And it does seem to be getting bigger and worse, and that’s what one finds when one reads good trashy novels. Their dilemmas get bigger and bigger until something explodes.