Art Buchwald in Paris: Fan Letters from Steinbeck, and an Invite to the Most Famous Wedding in the World

On the Legendary Humorist’s Time with Ben Bradlee, Humphrey Bogart, and the Windsors

Feature image courtesy of Diana Walker

Legendary humorist Art Buchwald would always say that the fourteen years he and his wife Ann spent together in Paris were “the scene of our happiest moments.” Part of the thrill was the extraordinary circle of friends and acquaintances they kept company with. Art played chess with Humphrey Bogart, played gin rummy with Ben Bradlee, and roamed the Left Bank with Orson Welles and Peter Ustinov.

They mingled with Ingrid Bergman; Audrey Hepburn; Lena Horne; Mike Todd and his beautiful young wife, actress Elizabeth Taylor; and the Duke and Duchess of Windsor. Ann and Art spent one bizarre evening with the Windsors when the Duke played recordings of “patriotic German songs” and sang along with great delight. “He was a dimwitted man,” Buchwald later wrote, “and I always believed England [owed] Wallis [Simpson] . . . for making him give up the crown.”

Art thought the Duchess, however, was “a very sharp lady and knew what was going on.” Knowing he was a restaurant critic for the Tribune, the Duchess once asked him to let them know about “any new restaurants [in Paris] you think we’d like—but none with garlic, please.”

Art Buchwald with Humphrey Bogart and Lauren Bacall. Courtesy Joel and Tamara Buchwald.

Art Buchwald with Humphrey Bogart and Lauren Bacall. Courtesy Joel and Tamara Buchwald.

They spent evenings with writers Janet Flanner and James Thurber of The New Yorker. (Buchwald once asked Thurber, who was nearly blind from an injury suffered as a child, what it felt like to lose his vision. In typical Thurber fashion, the humorist replied, “It’s better now. For a long while, images of Herbert Hoover were the only thing that kept popping up in front of me.”)

One evening the Buchwalds attended a dinner with British novelist and biographer Nancy Mitford, who was “one of the most anti-American people” Art ever met in Europe. “I once asked her what American she disliked the most,” Buchwald later recalled. “She replied, ‘Abraham Lincoln. I detest Abraham Lincoln. When I read the book The Day Lincoln Was Shot, I was so afraid that he would go to the wrong theater. What was the name of that beautiful man who shot him—John Wilkes Booth? Yes, I like him very much.’”

On other nights Ann and Art dined and shared gossip with the likes of novelist W. Somerset Maugham (who Art called “one of my favorite British people of all time”), or with legendary journalists Edward R. Murrow and Walter Lippmann, or with novelist John Steinbeck and his wife Elaine.

Art had long been an admirer of Steinbeck’s work—especially The Grapes of Wrath. In 1946, while still a student at USC, Buchwald got a job picking fruit on a farm in Northern California in hopes of gaining enough experience to write his own version of Steinbeck’s masterpiece. His planned adventure, however, quickly turned into a frightening misadventure. Guarded by men with shotguns during the day when out in the fields, then herded into filthy bunkhouses at night; it was a terrifying experience for Buchwald. Although he eventually escaped, he never forgot the terror he felt during the whole ordeal, later writing that he had nightmares about it for the rest of his life.

Now the opportunity to spend time with Steinbeck in Paris was a dream come true for Buchwald. And soon, to his great delight, the Pulitzer Prize– and Nobel Prize–winning novelist became an admirer of Art’s charm and his unique brand of humor:

JULY 27, 1953

[New York] Dear Art:

Have been wanting to tell you for a long time how much I am enjoying your pieces we get in the Trib here. You are getting a fine humorous form and also you are about the only man living who is setting down our ridiculous time in proper and good natured terms. You are developing very rapidly and it is a joy to read. And it’s in the real sturdy tradition of American humor too. At once most deadly and the most ingratiating.

Although the Herald Tribune was one of the most prestigious newspapers in the world, its Paris bureau offices at 21 rue de Berri were notable for their “scruffy” appearance. The whole setting “could not have been better designed by a movie-set director,” Buchwald once joked:

The floors sagged, and when the presses were running, the entire building shook. . . . The elevator creaked in pain. The limited space allotted to me could have gotten the Tribune in trouble with the Geneva Convention. Reporters’ desks were from the Clemenceau period and the lighting had been designed by Thomas Edison.

Ben Bradlee, the Paris bureau chief of Newsweek magazine, which shared space with the Tribune, remembered the offices as being “wonderfully ratty” and “grungy.” During cold months, a lack of heat was always an issue, requiring reporters to sometimes wear gloves while they typed. Buchwald’s typewriter and “cluttered” desk “faced a blind window which overlooked a soot-covered air shaft.” In such cramped quarters, his habit of chain-smoking cigars and laughing out loud at his own columns was a constant source of annoyance to his editors and fellow reporters.

And to help put out each edition of the paper there was an odd assortment of staff on hand. According to Buchwald, the French typesetters in the composing room (none of whom spoke a word of English) sang the Communist anthem “The Internationale” every twenty minutes and, to make matters even worse, the office mail clerk was almost blind, and the phone receptionist nearly deaf.

Despite the close quarters and dingy conditions at 21 rue de Berri, Buchwald loved being a Trib man. His weekly columns were now read and talked about nearly everywhere, and his readership was constantly on the rise. By 1955 his reputation had grown to such an extent that a mock Buchwald column titled “The Cat Prowls Again?” made a cameo appearance in the opening scene of Alfred Hitchcock’s film To Catch a Thief, a romantic thriller about a retired jewel thief named John Robie, starring Cary Grant and Grace Kelly.

By 1955 his reputation had grown to such an extent that a mock Buchwald column titled “The Cat Prowls Again?” made a cameo appearance in the opening scene of Alfred Hitchcock’s film To Catch a Thief.After only seven years in Paris, Buchwald had become a journalistic celebrity, prompting American radio personality Fred Allen to remark that Art’s column had surely “raised the stature of ink.”

The key to Buchwald’s style of humor was to “treat light subjects seriously and serious subjects lightly,” he once said. That formula was on full view in two of his greatest satirical successes while in Europe. The first was an offbeat and fanciful account of one of the most talked about weddings of the twentieth century; the second a comical roast of a powerful yet unwitting presidential aide who was no match for the Buchwald treatment.

*

During the spring of 1956, a fairy-tale story of royal romance took Art Buchwald and his friend Ben Bradlee on the road to Monaco. Earlier that year, American actress Grace Kelly had announced her engagement to Prince Rainier Louis Henri Maxence Bertrand Grimaldi of Monaco, generating a larger-than-life love story covered in newsreels and newspaper headlines around the world.

Just days before the royal wedding, Buchwald, Bradlee, and Crosby Noyes of The Washington Star left Paris and rushed to Monaco to cover the ceremony, despite the fact that none of them had an invitation. Leaving Paris by overnight train, the “Three Musketeers” (as Bradlee dubbed them) headed south, in the hope that their resourcefulness would get them some kind of inside scoop at the wedding. When they finally arrived at the Monte Carlo train station, there was not a cab in sight.

After a bit of scrambling, Bradlee spied a small taxi and waved it down, but he immediately realized that the portly third Musketeer, Buchwald, would never fit in the cab. “There’s no more room, Artie!” Bradlee yelled. Casting all honor aside, Bradlee and Noyes jumped in and ditched Buchwald, both laughing as they sped off to their hotel. However, as in most cases throughout Buchwald’s life, he would have the last laugh. After making his way to the hotel, Art sat down at his typewriter and, as Bradlee described it, “pulled a rabbit out of his hat, with what I have always believed was the best column he ever wrote.”

After making his way to the hotel, Art sat down at his typewriter and, as Bradlee described it, “pulled a rabbit out of his hat, with what I have always believed was the best column he ever wrote.”In a piece filed with the Tribune later that day titled “The Great Grimaldi Feud,” Buchwald wrote a spoof column claiming that the reason he had been “snubbed” and had not received an invitation to the wedding was that the Buchwald and Rainier-Grimaldi families had been feuding since the thirteenth century, and that the bitterness of the rivalry had prevented him from being invited. “The reason for the feud is lost somewhere in the cobwebs of history,” Buchwald facetiously wrote. “You won’t find a page in the history of Monaco where a Buchwald hasn’t offended a Grimaldi or a Grimaldi hasn’t offended a Buchwald.”

A year earlier, Buchwald wrote, he had tried to heal the bickering between the two families by coaxing his aunt Molly to invite Prince Rainier to attend his cousin Joseph’s wedding to a “nice girl from Flatbush.” But his proud and defiant aunt would have none of it. “No Grimaldis!” she told Art.

Now stuck in Monaco with no invitation to the royal wedding, Buchwald playfully declared that he was the latest victim in the seven-centuries-long feud. Sadly, he said with feigned amusement, “the Grimaldis still had it in for the Buchwalds.”

Art’s column was a stroke of genius. The next morning, shortly after the daily edition of the Paris Herald Tribune reached the Royal Palace, an invitation to one of the most magical weddings of the century was hand-delivered to Buchwald at his hotel.

_____________________________

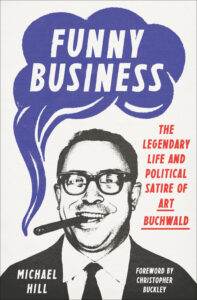

Excerpted from FUNNY BUSINESS: The Legendary Life and Political Satire of Art Buchwald © 2022 by Michael Hill. Published by Random House, an imprint of Random House, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.