Are We in the Middle of a Black Art Renaissance?

A Spiritual Manifesto for the Global International African Arts Movement

There has been a virtual saints and soul revival processional in the canon of Black arts globally since 2014—Amiri Baraka, Maya Angelou, Ruby Dee and Walter Dean Myers, and before that Chinua Achebe. Our griots—the repository of our culture(s) and original technologies—are moving to the other side of our cosmic reality where creativity and audacity color the demarcations between day and night.

Most recently, there have been the literary giants and our laureates of the 21st century: Toni Morrison and Derek Walcott. We would include Gabriel García Márquez, Carlos Fuentes and Julio Cortázar in that tribe for their engineering of the Latin American Boom which set the global stage for a new school of thinkers outside the conventions of Faulkner and Hemingway. Mission accomplished: New Age dawned.

Amiri Baraka, our firebrand and godfather of the Black Arts Movement (BAM), was one of the first to jump in line and light the celestial fire, so others could see it was time to ascend. His movement, our Black Arts Movement, was born from Malcolm X’s assassination in 1965. In fact, in the poem “Black Art” penned by Amiri for BAM trumpets, he writes:

We want live

Words of the hip world live flesh &

Coursing blood.

Or as Harvard’s Werner Sollors observed, Amiri observed the need to commit the violence required to “establish a Black World.”

BAM helped to usher in the boom of hip-hop, born in the 1970s when block parties became increasingly popular in New York City. Popcorn raps, freestyle battles and sheer rhymes over beats went “viral” in communities all over the USA before that term even existed (events not unlike 2014’s 16th-annual Harlem Book Fair).

The Global International African Arts Movement . . . is about moving our people forward through artistic and intellectual expression into spiritual expression.

From Afrika Bambaataa to Lauryn Hill, from A Tribe Called Quest to J Dilla, hip-hop packages together liberation, creativity and social commentary, and it is a global gift that the youth, marginalized and voiceless patrons embrace and cherish. Hip-hop stands on the shoulders of BAM. Lady Griot Poet Magistrate of the Black Arts Movement, Sonia Sanchez, certainly acknowledges the direct legacy:

Because when the bebop people started to play nobody could keep up with them. It was so fast you couldn’t even hear. I would always say to my kids when I first heard hip-hop, “I can’t hear it/I can’t understand” … It came at a fast pace and if you turned your head, you missed it. It was gone. The bebop, the bam, and the hip-hop.

Now, if we turn our heads to the future, we can see that a current movement seems to have been seeded, certainly in part, by President Barack Obama’s literary ambition and accomplishment, with Dreams of My Father and The Audacity of Hope, seeding a transcendent moment for America and the peoples of the world, where hope and change were homogenized and momentarily materialized in 2008 as a north star.

Perhaps, this could just as soon be dubbed “The Age of Obama,” but it is not. It is something much more. As Obama has noted, “I stand here… on the shoulders of giants.” Indeed, a generation of writers, artists, intellectuals, creatives, entrepreneurs, seers, visionaries, healers, mystics, clairvoyants, knowers, followers and more is awoken and activated. Names like Zadie Smith, Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, Jason Reynolds, Ta-Nehisi Coates, Kwame Alexander, Denene Millner, Colson Whitehead and Paul Beatty become standard bearers of powerful voices going back to antiquity, with the invention of culture, language and story.

The Global International African Arts Movement (or the Global I Aam) has grown organically from the Harlem Book Fair, beginning as a way to round out the global self-perception the diaspora holds of itself through mass media. For a quarter-century, the Quarterly Black Book Review’s (QBR also runs the Harlem Book Fair) mantra has been, “Our words, our lives, our stories.”

As such, it publishes reviews of books and provides literary content for, by, and about writers of the African Diaspora: this includes American, African, Caribbean, Latino, British, and other writers of African descent. It is fitting that the Harlem Book Fair holds space from the Harlem Renaissance, bridging the 19th to the 20th century for a movement which will bridge the 20th to the 21st.

In the 21st century we look to increase that consciousness and build upon this 20th-century platform. Max Rodriguez’s Harlem Book Fair and Quarterly Black Book Review occupy the same space as the independent book movements in New York City and Chicago in the 1960s and 1970s. We hold firm to director Shekhar Kapur’s observation that: “We are the stories we tell ourselves. A story is the relationship that you develop between who you are, or who you potentially are, and the infinite world.”

QBR has been called “The African American book review of record” by Martin Arnold, cultural critic of the New York Times. Along with the traditions of Troy Johnson’s African American Literature Book Club, Mosaic Literary Magazine, Cave Canem, Aaduna Literary Magazine, Black Bird Press, African Voices, Kweli Journal, Black Orpheus, Jalada, Callaloo, Killens Review of Arts & Letters, Chimurenga, Black Renaissance Noire, Third World Press, Xavier Literary Review, Home Slice and other online periodicals we see an effort made to precisely define ourselves.

We can also note QBR and the Harlem Book Fair, the Leimert Park Village Book Fair, Ujamaa Book Festival, Virgin Islands Literary Festival and Book, Anguilla Literary Festival, African American Children’s Book Fair, Schomburg Literary Book Fair, the Sacramento Black Book Fair and dozens of others are a continuing record of the global African expression.

In short, the Global International African Arts Movement (or Global I Aam) is about moving our people forward through artistic and intellectual expression into spiritual expression. We recognize that triumph and tribulation have brought us to our current place as the world’s single greatest ongoing eternal creative force. We are a celebration of our culture and an exaltation of people who have mastered the art form of spiritual rebirth and pure inspiration. Afro-form.

We cherish the moments when we, folks of African ancestry, connect and find each other in space and time.

We proverbially, literarily and perhaps one day literally, march, for enlightenment, higher consciousness, just human being. We celebrate our being members of a single human race. As BAM’s and Harlem Book Fair’s Sonya Sanchez has spoken:

The first writings I did were to my grandmother, this woman who loved me unconditionally. She would say to the Aunts, “Just let the girl be. She be alright. She going to stumble on gentleness one of these days.” I am not sure that I have stumbled on gentleness. But what I did know is I stumbled on people who were like me. People who decided they had to change the world.

The Global I Aam is this. We are now from different shores, with different stories, languages, but we are one. We are one. Through the Global I Aam, we can discover our collective uniqueness and common thread, curated in a way that only the Global I Aam can.

We cherish the moments when we, folks of African ancestry, connect and find each other in space and time. We find each other in history. We find each other through our differences, like the beautiful accents we infuse into and the manner in which we transform the English language, and of course, the diversity, yet oneness, of our artistic expression. Yes, we be alright. We be more than alright. Yes, We Be. Our sacred moments have dawned.

The Global I Aam, the spirit of togetherness, the divine inspiration that emanates from our ideas, voices and bodies.

The Global I Aam has already been moving, germinated in the first part of the 21st century. We simply aim to chart its course, giving form to the spiritual.

__________________________________

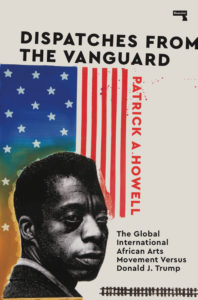

This is an excerpt from Dispatches from the Vanguard: The Global International African Arts Movement Versus Donald J, Trump edited by Patrick A. Howell, published this month by Repeater Books.

Patrick A. Howell and Mavin L. Mills

Patrick A. Howell & Mavin L. Mills are co-founders of the Global International African Arts Movement.