Are We Comfortable Encountering Strangers Anymore?

Sebastian Matthews on Balancing Suspicion and Good Faith

Beyond Repair is told through a series of encounters with friends and neighbors, colleagues and strangers, from early 2014 to spring 2019. It’s the story of my re-emergence after surviving and recovering from a major car accident. When I finally returned to the world—as father and husband, friend and brother—it became clear that we were all trapped in a traumatized state—reeling from one after another police shooting of unarmed African-Americans, stunned by yet another mass shooting—and that everywhere people were displaying signs of PTSD.

My interactions in daily life became more and more dysfunctional—us against them, red vs. blue, rich vs. poor. That my family and I live in Asheville, NC—a progressive town inside a conservative county in the mountain South—only made things more volatile.

I tried to enter into these experiences as conscious as possible of the potential divides and misunderstandings between us—including my own unearned privilege as a middle-aged white man—while working to make meaningful connection. I started close by then traveled out into the wider world. At the same time, we were raising our teenage boy, doing our best to help him navigate this new, challenging environment.

*

White men in trucks. What is it about them that shoots a brief goose of fear into my bloodstream? Is it imminent threat sounding in the revved engine? Derision caught in the side-view mirror? Or plain old disdain drumming its fingers on the drivers’ side door? A little of each!? All I know is I am walking through our suburban neighborhood, and a truck barrels past, not slowing nor moving over. That another swerves around the bend, almost clipping my dog, meeting my upraised hands with a jutting middle finger. And another drives right up behind me and rides my bumper all the way up the hill.

Just yesterday, downtown Asheville, a man steps around me in line and interrupts the conversation I’m having with an acquaintance. He is showing me a photo of his five-year-old boy holding up a large fish caught in one of the Biltmore ponds.

The man steps in closer. “That a bream?”

He’s got a smile on his face that I read as hostile. He wants me gone. But the father ignores the man, finishing his sentence about the peaceful water and how quiet it is out there with his boy.

I don’t know what gets the young man talking, but soon he is telling me that he is stationed in North Carolina, on furlough for two weeks to visit family back in New Jersey.

“Almost mystical,” he says.

The man interrupts again, smile getting bigger. “Hey, Mike, that a bream your boy is holding?”

Mike bursts into an equally large smile.

“Hell no,” he drawls, and lists all the fish his boy has or could have caught.

I don’t fish, so I don’t follow. Nor can I make clear sense of the quick-fire exchange. The two men have fallen into a bravado-fueled, friendly back-and-forth—it’s as if they’re flashing each other signs or showing each other their good-old-boy badges. I feel as though I am being erased from the moment, No Trespassing signs staked at my feet. The men chat and laugh in the corner as I slip back in line.

Later, at dusk, one more truck appears; it slows to a crawl and follows me up the street. What’s with people these days? Are they so sick of their lives that they need to lash out at strangers? To hate them for being something foreign or different?

I turn to face my nemesis, who has rolled down the window. “Whadya want?”

The man smiles, remains silent. There’s power in a comfort with silence.

“How old is that dog of yours?” he asks, leaning out the window. He’s talking about the lab, just a puppy, bounding over and standing up as if seeking the man’s arms. The man laughs. The look in his eyes is pure sadness.

*

. . . on a flight from Charlotte to Newark

The young Marine stows his carry-on bag in the overhead compartment before sitting down in the aisle seat. He keeps the shiny, white-peaked utility cap on his lap. The flight attendant asks if she can put it in the overhead bin. The young man politely refuses and places the cap under the seat in front of him, arranging his feet around its pristine edges. His hair is dark black, his skin long-winter pale.

I don’t know what gets the young man talking, but soon he is telling me that he is stationed in North Carolina, on furlough for two weeks to visit family back in New Jersey. That he is recently divorced. I ask how long the marriage lasted. He bows his head and mumbles, “Not long.”

He talks at length about the difficulties of living on base as a young married couple; how his ex-wife got lonely and went AWOL.

“If she’s holed up where I think she is, well, you might see me on TV.” He looks directly into my eyes before fiddling again with his headphones. He takes his Coke from the stewardess, smiling politely when she hands him the cup and napkin. “Really, I am a pretty calm guy.”

When I ask him what size family he’s returning to, he smiles, listing off its members.

“Mother, sister, younger brother, a couple of cousins.” There’s a long beat. “And my father…I guess.”

A few more beats: “He’s a nice guy when he’s not drunk.”

Turns out his dad is a firefighter, or was one until he drank himself out of a job. He was six years from retirement, on his way to being chief. My seatmate leans down and shifts his cap a little. Later, as the plane begins its gradual descent, the young Marine tells me more about his life in the service, about how he often serves as his platoon’s designated driver.

“I drink,” he says, “but only a beer or two. I just turned 19. I watch myself.”

Lately, he says, they have been training for cold weather action. He looks proud.

“I am used to the heat. Not sure about the cold, though. I get shivering pretty fast.”

When I ask him whom he wants as our next president, the young Marine frowns, lips pursed. He puts on his music and disappears into it, eyes closed.

Near the end of the flight, everyone’s awake, preparing to disembark. I ask the soldier about women in the Marines, thinking of the two women officers I just read about who completed the special ranger training. He doesn’t answer at first.

“It’s biological,” he says, as we wait for the plane to taxi to the gate. “Men are programmed to take care of the female first.”

At the register, I noticed an older gentleman hovering by the door. He seemed tuned into my presence.

He shifts in his seat. “And I am not saying it’s right. But it’s true.” I don’t know what to say to that.

“And there is no place for that in battle. There’s a protocol.”

The young man shakes his head sadly, and carefully lifts up his cap, placing it in his lap. He puts his headphones back on and blasts music until the line starts moving. When it’s his turn, he stands up and retrieves his bag. I watch him inch forward to the door, fixing the cap on this head, and I worry for his ex-wife’s safety.

*

Last night Avery needed picking up at Tarwheels, a roller-skating rink one township over. I wanted to get him by 10:30 even though the place closed down at 11. It was a safe scene, still I worried about leaving a preteen out on his own so late. Even though he knew to stay inside, what would it take for him to break that rule? A couple of cool teens urging him out to take a hit off . . . ?

I headed out right around ten, stopping to get gas. At the register, I noticed an older gentleman hovering by the door. He seemed tuned into my presence; by the time I was done paying, he was standing behind me, in my blind spot.

(Which reminds me, there’s this scene in an early episode of The Americans in which the Russian spy—disguised as a normal, suburban American Dad—asks two thugs to get out of his blind spot. He’s talking to this badass boss man. They don’t move. He asks again, looking nervously over his shoulder. They don’t, so he kicks the living shit out of the men. When he’s done, he turns back to the boss and says, “I told them to get out of my blind spot.”)

So I gave my guy a stare. He waited for me to grab my things off the counter before approaching.

“You going out toward Arby’s?”

“I work at the grocery.”

He showed me the apron in his hand. “I need a ride back to my room.”

My first inclination was to shake my head and walk away. But something told me to give him a chance. So I stared a little longer. He didn’t look like a serial killer. Actually, he seemed like an exhausted man in need of some sleep.

“Ok, let’s go.”

The man followed me to my car, climbed in, gave me his name, and sat quietly as we headed east on Tunnel Road.

“You staying at the hotel?”

“At the veteran’s place,” he said.

“The one across from the Dollar Store?”

“Yeah.”

He looked over at me.

“Most people don’t know the place exists.”

“Well, I’ve lived in the area a while now.”

“It’s good,” he said, “to know where things are.”

A few minutes later, we pulled up outside the hotel. The man got out, thanking me as he shut the car door. I watched him join a gathering in the well-lit lobby.

When I got to the roller rink, Avery was waiting for me at one of the tables next to the video games. He looked exhausted.

“Let’s go,” he said.

He skated wearily—and gracefully—to the car. I drove home, passing the vets in their fishbowl, letting the song on the radio serve as talk.

__________________________________

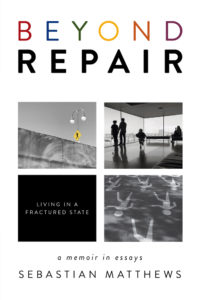

This excerpt is from Beyond Repair: Living in a Fractured State by Sebastian Matthews (Red Hen Press, 2020). Reprinted with permission from the publisher.

Sebastian Matthews

Sebastian Matthews is the author of a memoir, In My Father’s Footsteps, and two books of poetry, We Generous and Miracle Day. His hybrid collection of poetry and prose, Beginner’s Guide to a Head-on Collision, won the Independent Publisher Book Awards’ silver medal. Matthews is also the author of The Life & Times of American Crow, a “collage novel in eleven chapbooks.” His work has appeared in or on, among other places, the Atlantic, Blackbird, The Common, Georgia Review, Poetry Daily, Poets & Writers, The Sun, Virginia Quarterly Review, and the Writer’s Almanac. Learn more at sebastianmatthews.com.