Arctic Rush: Inside the 19th-Century Craze to Reach the North Pole

Erling Kagge on the Early Years of Polar Exploration and the Timeless Phenomenon of Human Hubris

Interest in Arctic expeditions and the North Pole exploded in the 1840s and 1850s. In Great Britain, but also in the US, interest was fueled by the rescue operations to find John Franklin and the other survivors, and later the race between nations to reach the North Pole. It was Lady Jane Franklin, wife of the missing Franklin, who triggered what was called at the time Arctic fever.

The North Pole has always been associated with competition. Initially it was simply the race to get there first. But many races have since followed. I have only taken part in one, and that was to be the first to reach the Pole without the help of dogs, depots, and snowmobiles. Others have competed to be the first person to go there alone, the first person from their country, the first to go there and come back unsupported, the first to cross the Arctic Ocean in winter.

When we went there, there were other expeditions, from Russia, South Korea, the UK, and Canada, who were also trying to reach the North Pole. It was a busy time, out on the ice. The British team were our toughest competitors. The expedition was led by the former SAS soldier Sir Ranulph Fiennes, who has been named as the World’s Greatest Explorer in the Guinness Book of Records. Ran, as we call him, set the record for the expedition to get farthest north unsupported in 1986. The 1990 expedition was made up of two men, the other being the English doctor Mike Stroud. (Børge and I never understood why there needed to be a leader for two men.)

The more prestige an expedition could muster, the more money and state support followed.

I was not aware that there was a new race to the North Pole until 1987. That year, I read an article in National Geographic magazine, the publication read by most explorers at the time, in which, having reached the North Pole on foot with aerial support, the Frenchman Jean-Louis Étienne asked: “Will anyone ever reach the Pole under his own power, entirely unassisted?” For me, the question was an invitation to try.

*

The mission of Lady Jane Franklin’s husband had been to explore the Arctic; her mission became to prompt, persuade, and pressure the Admiralty and other private institutions to search for him. Between 1848 and 1859, there was a race to find any survivors. More than fifty expeditions set out from the US and Britain. The search team captured Arctic foxes and attached written messages to them addressed to Franklin and his men, giving the position of rescue ships. Then the animals were released again. The hope was that Franklin might shoot the foxes for food and so find out that a rescue operation was in the vicinity.

A similar message was attached to balloons, which were then released to float over the ice, water, and skerries. Private and government expeditions competed to find clues as to what might have happened. There is no record of how many people died during these rescue attempts, but having read numerous accounts of expeditions to the Arctic and subsequent rescue operations, I think that far more people died in connection with the rescue than with the expedition itself.

Six years after the race to find Franklin had begun, the explorer and surgeon John Rae, from the Orkneys, returned to London in 1854, following one such rescue expedition. He reported that the Inuits had noticed that the British refused to eat the blubber and innards from seals and walrus so essential to the Inuits’ diet, and that they often died from scurvy and starvation as a result. In his report to the Admiralty, Rae described the remains of some bones he had found, presumably from Franklin’s expedition, that looked as if they had been cooked and cut with a metal knife, and from “the contents of the kettles, it is evident that our wretched countrymen had been driven to the last dread resource—cannibalism.” It seems that the men of the Admiralty had grown tired of sending new expeditions north, and wanted an end to it, so they leaked this information to The Times. People were appalled. The idea that civilized men could eat each other was horrifying to the Victorians.

Readers of newspapers, books, and periodicals, and lecture audiences, had lapped up the details of countless rescue operations and the uncertainty surrounding the fate of the polar explorers. In the spirit of Edmund Burke, they were both captivated and repelled by the terrible sequence of events. But, as Burke had predicted, the readers’ experience of the sublime faded into terror when the specter of scurvy, starvation, and cannibalism loomed.

A good “sublime” story should stoke two strong emotions in the reader: first, shock or helplessness, then enormous relief at what rational people can achieve when faced with grave danger. The latter was missing from the story of Franklin’s final expedition.

Franklin’s wife, Jane, and the writer Charles Dickens were two of the most vocal critics of these claims of cannibalism. It must be understandably hard to accept that your husband may have eaten one of his own crew. Dickens’s explanation of why he thought it was not possible is more interesting—and more revealing. He claimed in his own periodical, Household Words, that the English, with their superior culture, could never be tempted by what he, quite correctly, called “the last resort.” It must have been the more primitive creatures, the Inuits, whom he preferred to call “lying savages,” who had succumbed to cannibalism. Dickens did not accuse Rae of lying, but said that the stories the Inuits had told him were nothing more than “the chatter of a gross handful of uncivilised people” and should be left untold. For Dickens, it was natural to think that a good Englishman would rather starve to death. Unlike other nations and races, they were far too civilized to eat human flesh.

*

The interest in expeditions to the North Pole through the nineteenth century to 1909, when Robert Peary and Frederick Cook claimed to have reached the Pole, must be seen in light of the technological developments in the same period. As interest in the North Pole and polar explorers like William Parry and John Franklin grew, the first steps in the globalization of news and literature propelled their stories around the world. The culture of the international celebrity was born, and polar explorers became famous throughout the greater part of Europe and eventually the US.

Until the start of the 1800s, access to literature, be that novels, poetry, or nonfiction, was limited. In the first half of the century, thanks to new technology, literature started to be mass-produced, and could be distributed more efficiently by train. More people learned how to read, gas lighting became more readily available in people’s homes for them to read by, prices also became more affordable as printing became steam-powered, and as living standards rose, people gained more free time and disposable income. The novel Frankenstein and books by William Parry and John Franklin were sold in bookshops and kiosks, often in train stations.

Telegraph lines were installed along the railways, and suddenly news could reach the towns and cities in no time at all. The expeditions and their heroic feats became headline news. Newspapers published national and international news every day. In August 1858, a telegraph cable was pulled along the seabed between the US and Great Britain. It fell apart three weeks later, and a new cable was laid in 1865, which also broke. Another cable was successfully laid the following year and cross-Atlantic communication shrank from two weeks to two minutes.

Expeditions and newspapers were heavily dependent on each other. The media needed a constant supply of new heroes and dramatic stories. And the more prestige an expedition could muster, the more money and state support followed. Newspaper barons planned and organized their own polar expeditions, and the rights to stories and books were sold before the expeditions had even set off. Sometimes journalists even became explorers themselves, as was the case with Henry Stanley, who went off in 1871 to find David Livingstone in present-day Tanzania.

*

The American polar explorer Anthony Fiala once said that one does not give up until “the command given to Adam in the beginning—the command to subdue the earth—has been obeyed.” It seems that this became a kind of creed for the US, which was starting to claim its position as a polar nation.

The expeditions were militant in their ambitions to conquer nature, map the ocean, carry out scientific studies, and acquire territories on sea, land, and ice. They were also militant in their treatment of other people and cultures, and assumed it was their duty to tame and subjugate the forces of nature. Polar history entered an era that Joseph Conrad described as Geography militant.

Like several other polar explorers, the American Elisha Kent Kane (1820–57) was inspired to travel north when he read about the missing John Franklin. Kane lived in Philadelphia and was involved in the latter part of the US’s invasion of Mexico in 1848 and 1849. He had no experience of the Arctic, but was convinced that America should help to find Franklin. And not only should America offer its assistance, but he himself was the best person for the job. Kane took part in two rescue operations before he put together his own expedition in 1853. It was far smaller than the British expeditions, but he set off north as captain of the brig USS Advance.

As soon as there was the slightest bit of swell, Kane was violently seasick. He also had no idea how to navigate, had no experience of leadership, and was plagued by rheumatic fever. Only one of the men on board the Advance had any relevant experience from the Arctic region. The reason the crew was so unsuitable was that it had been hard to find volunteers. Kane had eventually been forced to take on sailors without work who were hanging around the harbor.

Instead of heading toward the area where Franklin might be, Kane decided to look for him somewhere he was highly unlikely to be: Smith Sound, which lies east of Ellesmere Island, closer to Greenland. His intention was in fact to find a new route to the North Pole, fighting his way through to ice-free waters, so as to be the first to reach the Pole. By saying it was a rescue operation, he cleverly secured financial support and a boat. American sponsors liked the idea that their young nation could take over where Great Britain had failed, and save the superpower’s missing superhero.

The expeditions were…militant in their treatment of other people and cultures, and assumed it was their duty to tame and subjugate the forces of nature.

When Kane’s expedition reached northwest Greenland, he proved that while he might be a poor sailor and inexperienced polar expedition leader, he was a sound pioneer. He brought something new to polar exploration. Unlike Parry and Franklin, he spent time with the Inuits to learn how to drive a dogsled, the best mode of transport for crossing the ice.

In 1854, Kane’s plan was to abandon the Advance when she became beset by ice, and carry on north. But he made the same mistake as countless polar explorers. He gave in to his restlessness and set off too early, when the temperature was around -40°F. He ended up having a mental breakdown along the way. This seems only natural to me, given that he had started the preparations to become an explorer only some years before, by spending a few nights in a tent close to his home city of Cincinnati.

As they trekked north, Kane became convinced that a member of the expedition was a polar bear and gave orders for him to be shot. Fortunately, no one obeyed the order. But two of the crew died later on their return: one from tetanus and the other after his foot was amputated. Kane did not let the deaths or his own mental health deter him. He headed north again the same summer, with those who were still healthy enough to go. At some point, one of the team climbed a ridge to look around. To the northwest, he saw open water and clouds heavy with rain, and believed that the expedition had discovered the ice-free Arctic Ocean.

Pierre Berton concluded in his book Arctic Grail that it was a combination of wind, waves, and wishful thinking. It is hard to know how convinced the man was of his discovery, but Kane, who was waiting down by the sleds, was in no doubt. His expedition had achieved what generations of explorers had dreamed of: open water all the way to the North Pole and the Pacific. The sensational discovery would justify the expedition, but still he felt they could achieve more. Just like myself, Kane also wanted to impress his father. His hope was to be able to “advance myself in my father’s eyes by a book on glaciers and glacial geology.”

The intention was to sail home again in late summer 1854, but the ice did not melt as they had hoped and Advance remained trapped. Kane decided that they would all stay with the boat for a second winter. They had managed to keep the temperature on board the boat above zero the winter before thanks to the Inuits who had taught them how to insulate it with moss and peat. But the crew mutinied, and some of the men started to walk south in the hope of avoiding another winter.

Nearly a year later, on May 20, 1855, Advance was still stuck in the ice. Kane and the remaining men abandoned the boat and walked for eighty-three days to Upernavik, on the west coast of Greenland. In a farewell letter left on board, in case they too went missing and someone found the boat, Kane wrote that they had so little coal left that they would soon have to start burning the ship’s timbers. Staying aboard was no longer an option. The last things they did on board were to pray and quietly pack a portrait of John Franklin.

Only one man died on the return journey—no mean feat, given all that they lacked and the number of men with scurvy. The US dispatched two ships to find and rescue the expedition in summer 1855. Two years of arduous struggle, frostbite, hunger, and very poor hygiene had rendered the men unrecognizable. Even Kane’s brother, who took part in the rescue operation, failed to recognize his dirty, exhausted, bearded brother when they met.

__________________________________

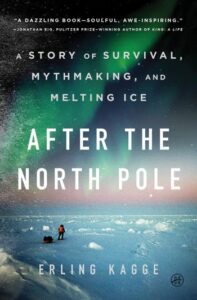

From After the North Pole: A Story of Survival, Mythmaking, and Melting Ice by Erling Kagge. Copyright © 2025. Available from HarperOne, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers.

Erling Kagge

Norwegian adventurer, philosopher and acclaimed writer Erling Kagge is the first person to complete the “Three poles challenge”—reaching the North Pole, the South Pole, and the summit of Mount Everest on foot. After this record-breaking feat, Kagge attended Cambridge University to study philosophy. He is the author of such beloved books as Silence: In the Age of Noise and Walking: One Step at a Time. He has written for the Financial Times, the New York Times, and The Guardian. He lives in Oslo, Norway.