I’ve always felt like a plant-person, moss and lichen covered; the land a part of me and me of it. The Irish landscape I grew up in is riddled with stone walls and stories, seventy thousand placenames and countless fairy trees. Irish placenames are derived from hidden histories or trees that used to grow there, ghost forests. Dair means “Oak” and is found in many placenames around Ireland. Townlands contain Cill, Irish for “cell” or “church,” demonstrating how intimately entwined our very cells-selves are with the Catholic church! In the first experiment in colonization, our language was beaten out of us. We had to learn in secret “hedge schools.”

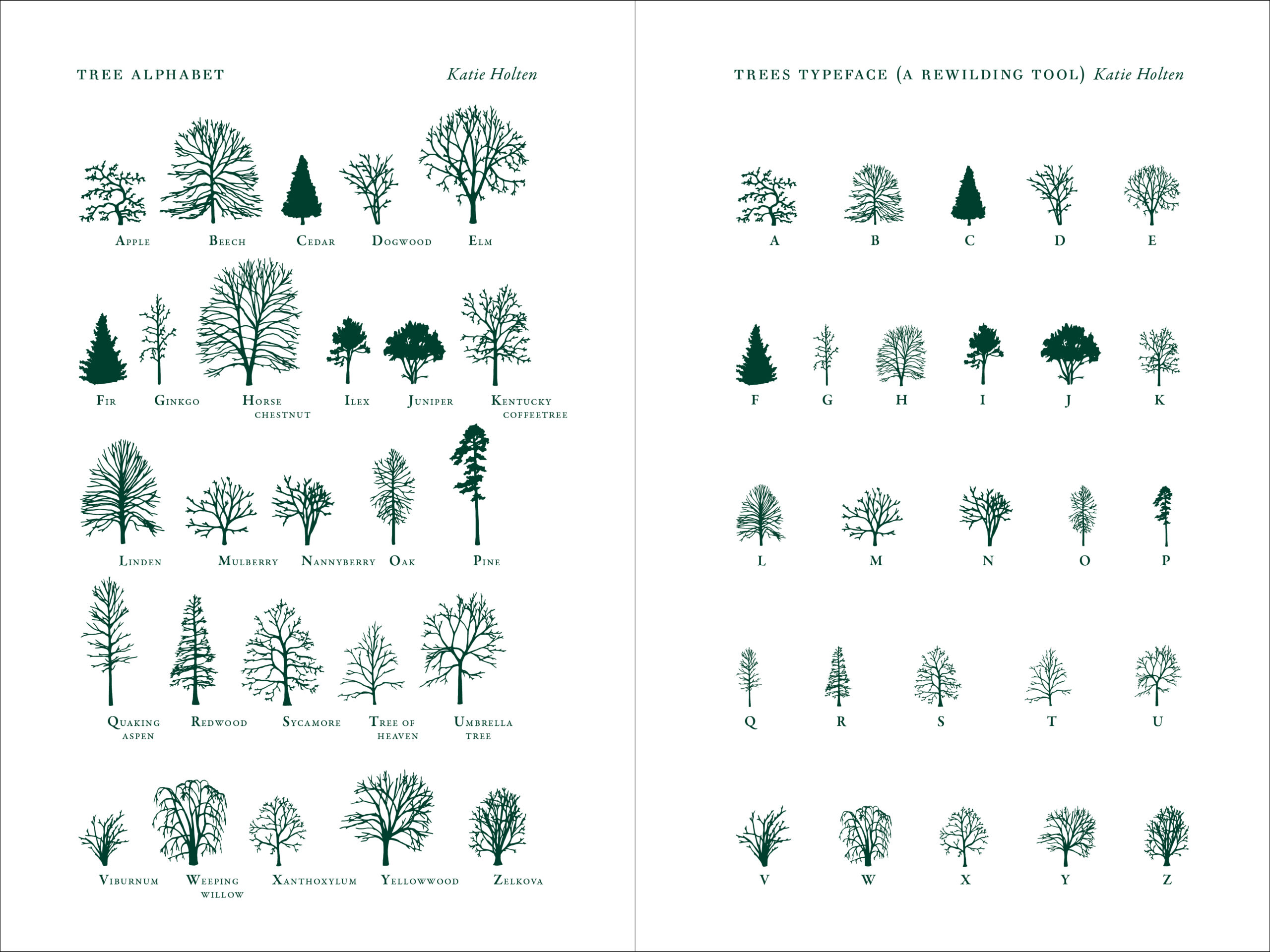

Ireland’s medieval Ogham, sometimes called a “tree alphabet,” used trees for letters. The characters were called feda, “trees,” or nin, “forking branches,” due to their shapes. This ancient writing was read from the ground up—each character sprouting from a central line, like branches on a tree. Journeying from the heartwood of ancient Ogham to today’s emojis, Aengus Woods introduces us to the strangeness of an alphabet of trees.

Written on bark, it is no coincidence that some of the first forms of writing used trees. Our capacity to produce language is innate, like a trees’ ability to produce leaves. Buds burst with potential stories. Words are alive, emerging from and evolving with culture. What if we plant living time capsules with secret messages written to our future selves? Why not make our words matter by planting them? We could seed secret messages of resistance, plant blooming poems and cultivate landscapes of renewal.

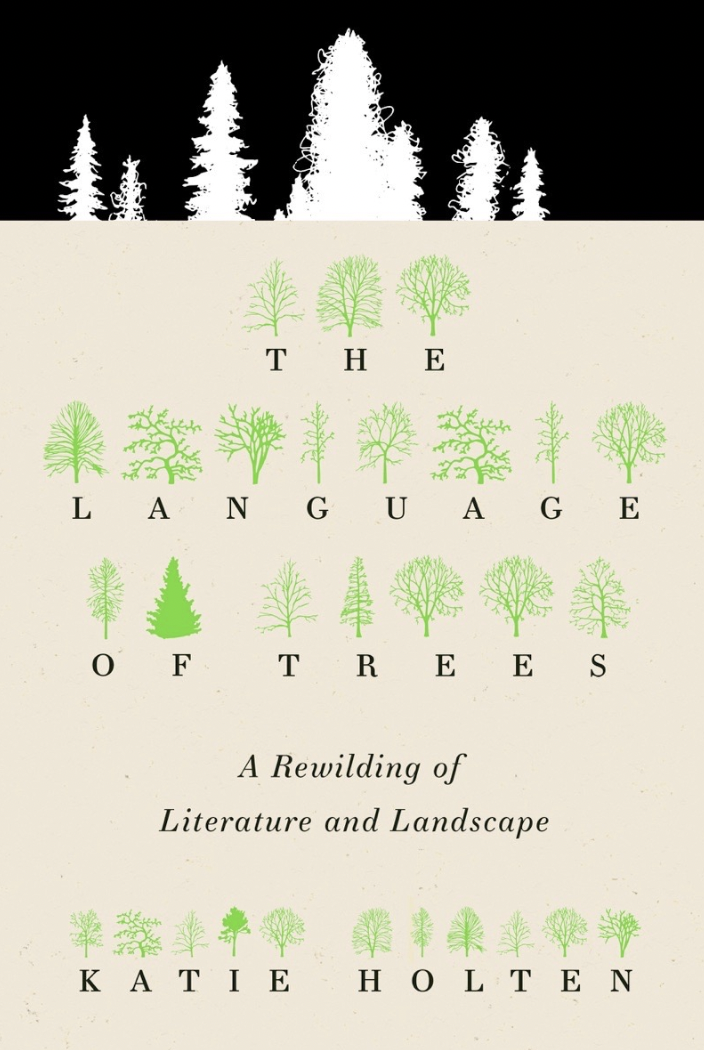

I created a Tree Alphabet—a new ABC—by taking each of the 26 letters of the Latin alphabet and creating a corresponding tree drawing. These new “characters” were converted into a font: a typeface that I call Trees. This font, the first of several, lets us type with Trees, translating our letters into trees, words into woods and stories into forests. I used the font to make the book About Trees, which was published as a limited-edition artists’ book by Broken Dimanche Press in 2015. I’m thrilled to have an opportunity to remake About Trees as The Language of Trees. At the heart of these books is the Tree Alphabet, a living alphabet that can be planted, allowing us to seed stories, watch them sprout and grow.

The Language of Trees is an archive of human knowledge filtered through many branches of thought. I hope the book takes readers on a journey—from prehistoric cave paintings to creation myths, from Tree Clocks in Mongolia and forest fragments in the Amazon to Emerson’s language of fossil poetry, from Eduardo Kohn’s anthropology beyond the human to Robin Wall Kimmerer’s call for a new grammar of animacy—unearthing a grove of beautiful stories along the way.

Written on bark, it is no coincidence that some of the first forms of writing used trees.We have much to learn from trees. Kimmerer and other scientists like Suzanne Simard and Toby Kiers study tree communities, inspiring ways for us to learn from—and live with—the natural world. They show how trees talk to each other using mycorrhizal fungi, an underground hyphal network.

This natural language exists beyond our understanding of communication because trees “speak” in frequencies that humans can’t perceive. We can hear leaves rustle, branches creak and squeak in the wind, but trees make more sounds that are inaudible to the human ear but discernible by other beings. For example, trees undergoing stress form tiny bubbles inside their trunks creating ultrasonic vibrations. Trees can also be transformed into instruments of joy, like Yo-Yo Ma’s cello made from spruce and maple.

Artists, writers, activists, musicians, engineers, philosophers, farmers, educators—people everywhere, and throughout time—have loved and learned from trees. Historians, linguists, and mathematicians use tree forms to understand the world. A simple mathematical game of trees shows us that there is a number—tree—that is so large no human can comprehend it and physics can’t describe it.

A few years before I was born, Christopher Stone, a Professor of Law at the University of Southern California, had an epiphany while speaking with his students—what if trees, like people, had rights? “I am quite seriously proposing that we give legal rights to forests, oceans, rivers and other so-called ‘natural objects’ in the environment,” he wrote.

Today the movement to recognize these Rights of Nature is inspiring people around the world, with Indigenous communities leading the way. Almost all successful Rights of Nature cases—so far—protect bodies of water. Why not trees? Paul Powlesland, founder of Law for Nature, told me, “I’m not aware of a draft Rights of Trees in general as they seem more difficult to conceptualize than rivers.” I believe we will soon see Rights for Forests and Trees.

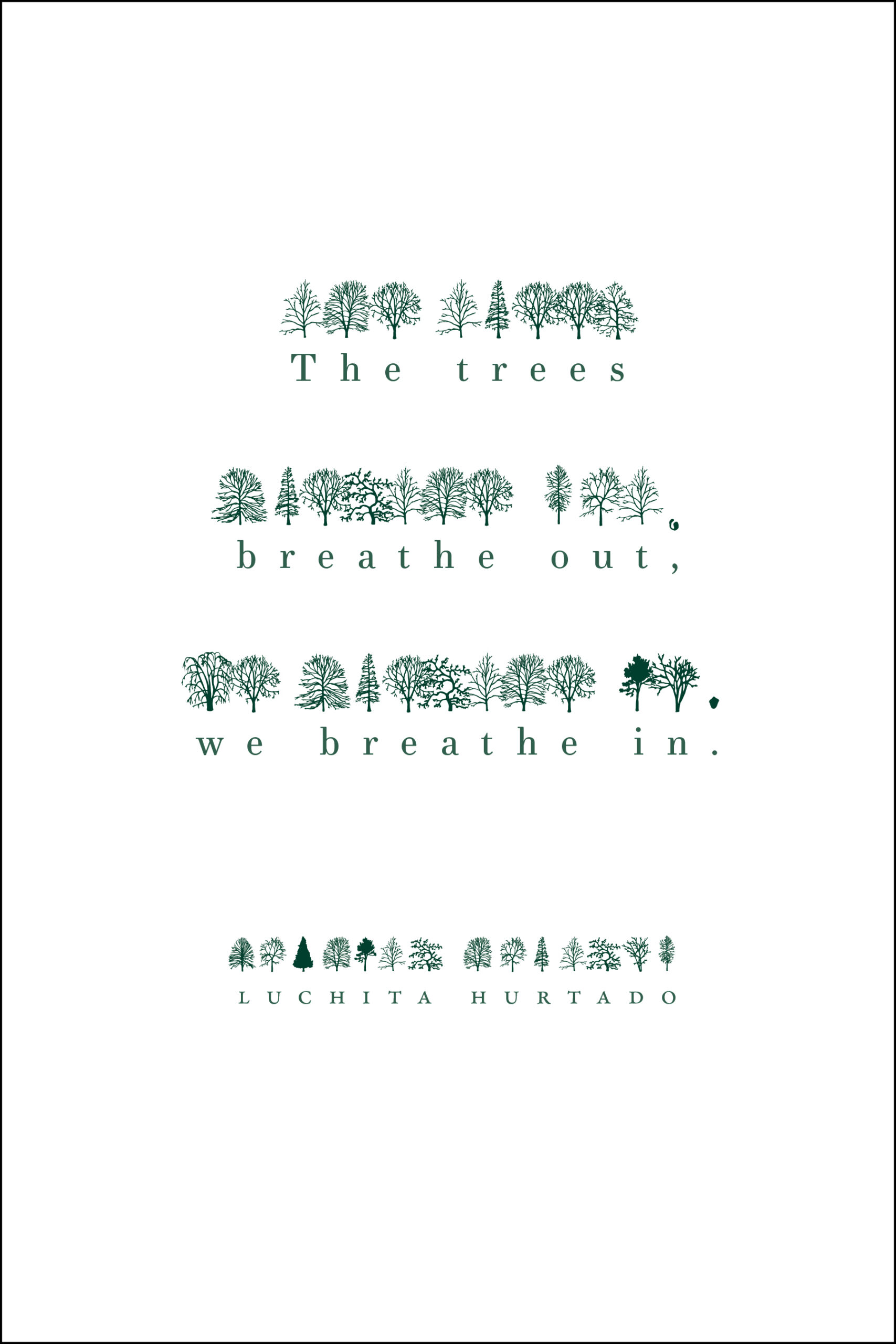

Luchita Hurtado, courtesy the estate of Luchita Hurtado and Hauset & Wirth.

Luchita Hurtado, courtesy the estate of Luchita Hurtado and Hauset & Wirth.

The Climate Emergency demands that we learn the languages of trees and speak on their behalf. Learning other languages creates empathy, compelling us to reconsider our relationships with other beings. If trees have memories, respond to stress, and communicate, what can they tell us? And will we listen?

Listening, speaking, reading and writing are how humans communicate and make sense of the world. The alphabet is how we organize information and knowledge; our networked world depends on it. Trees, the font, lets us renew our relationships with language, landscape, perception, time, memory and reading itself by slowing the reader down to decipher words in the woods.

Translation is perhaps the most intimate form of reading. When we translate our words into glyphs, such as trees, it forces us to re-read everything. The Tree Alphabet forces us to revisit the past, re-present the present, and reimagine the future by translating or rewriting what we think we already know.

Artists, writers, activists, musicians, engineers, philosophers, farmers, educators—people everywhere, and throughout time—have loved and learned from trees.And so letter by letter, tree by tree, we can reforest our stories, communities and our imaginations, reimagine public spaces, reconsider “monuments” and restore biodiversity while rewilding language. We can also ingest the alphabet, seeding our stories in plant DNA, encoding messages at the molecular level. History shows us that we become the stories we tell ourselves and our children. What stories do we want to leave behind? What do we want our ancestors to remember us for?

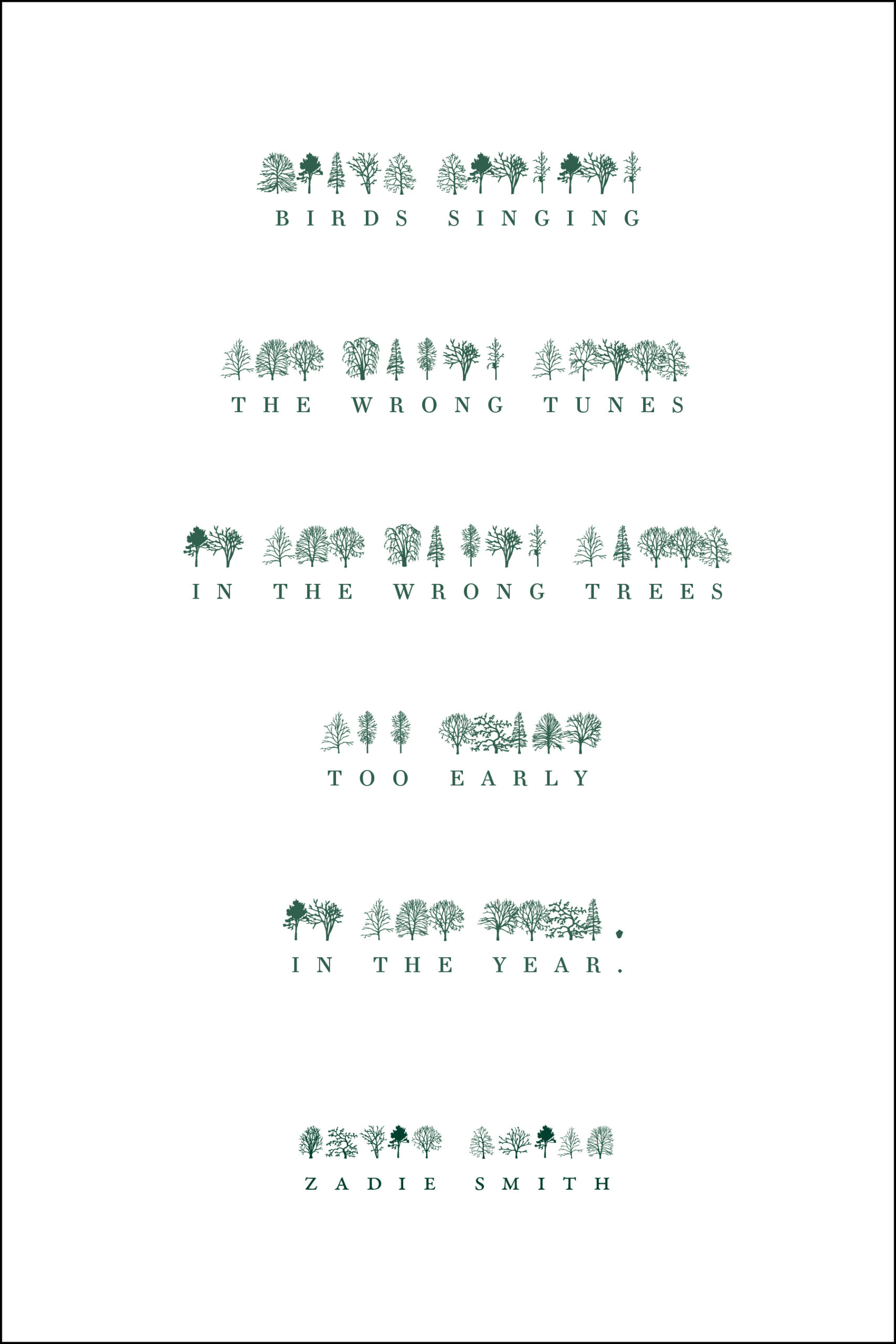

Courtesy Zadie Smith.

Courtesy Zadie Smith.

The Language of Trees gathers many voices, both human and nonhuman, offering ways to learn from, through and with trees. Activists, healthcare workers, guardians and warriors like Winona LaDuke, Nemo Andy Guiquita, Kinari Webb and Valerie Segrest articulate the urgency of this moment by sharing their indigenous knowledge acquired through many generations. I am grateful for Tree People.

People and trees have always been entwined. When we protect plants, we protect ourselves. Today we are teetering on the edge of extinction along with most of life on Earth. The Amazon is on the verge of tipping from life-sustaining rainforest to savannah. Our civilization is sleepwalking into apocalypse. But when I’m shouting in the streets at climate protests I am surrounded by thoughtful, kind, powerful, joyful, determined people fighting to protect people, plants, water, trees and truth by working to create a better world. We need to nurture their messages of hope.

The alphabet is magic, a way to love the world intimately. With these 26 little letters we can create any word in the universe. Letters of the alphabet are like seeds planted on a blank page. I offer the Tree Alphabet as a gift for those who want to fall in love with the world by rewilding their words.

Learning the language of trees can help us think like the multicellular organisms that we are, inspiring new ways to live and work together. Trees can help us rewrite the broken stories that we have been telling ourselves. Today, in this time of planetary emergency, we need to reread origin stories and rediscover other ways of living in harmony with our kin. Beautiful re-imaginings are happening everywhere—people are Rewilding, Reforesting, Restoring and creating Radical Hope.

I offer The Language of Trees as a celebration of trees and our entangled relationship with them. I hope this book inspires us to consider how our human nature might re-merge with the state of nature. The book is also a call to action. An ecological civilization based on Rights of Nature is a survival imperative. Please join me in declaring emergency and advocating for the Rights of Nature, the rights of trees, forests, peatlands, rivers, and planet Earth.

Dear reader, I invite you to download the free Trees font. Translate your words—your tweets, thoughts, and twigs of reason—into trees. The act of compos(t)ing love letters to our future selves might just be what makes our future selves possible.

When I feel overwhelmed by what we’ve caused—climate change, pandemics, poverty, biodiversity loss, migration, war, ecocide—I find solace in the beauty of the living world, especially in trees. Trees are truthful. They fill my heart with joy. Their simplicity and quiet beauty—alone on a city sidewalk or together in a forest—slows down time. Tree Time occurs in ever widening circles, like tree rings. If humans embraced Tree Time we would understand that time is not linear. Past and future are as real as now, meaning our actions today will resonate with as yet unfurled leaves on our family tree.

Shortly before she died in August 2020, aged 99, the extraordinary artist Luchita Hurtado told Andrea Bowers, “Trees breathe out. We breathe in.” Another world is possible. Together—with trees—we must breathe her into being.

__________________________

From the afterword from The Language of Trees, by Katie Holten. Courtesy Tin House Books.