Annie Proulx on the Lost Ecological Paradise of the English Fenlands

A Story of a Tearing the Infinitely Complex Web of Life

Alexander Pope’s eighteenth-century idea of genius loci appears in his Moral Essays as advice to landscape designers to keep in mind the “genius” or spirit of a natural place. This still has meaning when considering fens, bogs and swamps. I wanted to understand why we are suffering disasters of climate change, deforestation, drought and flood, runaway fires, viral pandemics, headaches, depression and political unrest, and if the loss of natural wetlands was a key element in this unraveling I wanted to know something of how they formed, how they changed and why, when humans ignored the genius loci, they disappeared.

I wanted to know how humans interacted with wetlands in the past and the present. The old image of an infinitely complex “web of life” holding the world together is still serviceable, but the web’s self-healing gossamer has been torn by humans in so many places it no longer functions. I found the story of the English fens was a story of the tearing-apart.

Peat builds up in fens, bogs and swamps and all of these stages are constantly in flux. The wetlands are related through a successional gradation that can end as a field of soy beans or a parking lot. After the marine marsh the fen appears, defined as a “peat-accumulating wetland that receives some drainage from surrounding mineral soil and usually supports some marshlike vegetation.”

In their day the English fenlands were the best-known of their kind. Once as much as 6 percent of Great Britain was wetland, most extensively along the east coast of Norfolk, Lincolnshire and Cambridgeshire known simply as “the Fenlands.” They were a watery mix of fresh water from rivers and streams, sea water and the land around the Wash where the Ouse River entered the North Sea—fen water deep enough for eels and fish and boats. There were hills and islands of dry land high enough for houses and gardens.

The old image of an infinitely complex “web of life” holding the world together is still serviceable, but the web’s self-healing gossamer has been torn by humans in so many places it no longer functions.

My interest intensified when I read Eric Ash’s The Draining of the Fens, his study of the sixteenth- and seventeenth-century drainage projects, an exploration of how vested interests and political clout reshaped a large wetland region and nurtured the nation-state at the cost of its ancient ecology. The generous character and extent of these fens seemed beyond anything I had known of England’s topography. Ash frequently referenced The Fenland, Past and Present by the meteorologist Samuel H. Miller and the geologist Sydney B. J. Skertchly, published in 1878, and one of the first attempts at a descriptive history of the fens.

When my print-on-demand copy of The Fenland arrived I scanned the table of contents, the list of illustrations, and then the Subscriber’s List (a publisher’s old way of making sure there was enough money in the kitty to pay for printing a large book unlikely to be a hot seller) in hope of finding a luminary of the day, perhaps Darwin, who was then still alive. He was not listed as a subscriber but turned up in an appendix as a contributor of unspecified information—possibly on an invasive North American water weed.

Toward the end of the list I saw the name Alfred Lord Tennyson, followed by a black blotch. An inky pen had obliterated the honorific “Poet Laureate” and above the scratched-out words had written “Plagiarist and Ass” in spiky anonymous strokes of his pen. There was more scribbling— much more—throughout the book. Since I knew nothing of the defacer but his strong masculine handwriting I thought of him as the Acerbic Hand.

Where Miller and Skertchly quoted several verses of “Camelot” he wrote “ROT” in two-inch-tall letters. Where the authors referred to “the poet” the Acerbic Hand altered it to “so-called poet.” But when the editors added “a few passages in the writings of the Poet Laureate, whose style bears the impress of Fen scenery and colouring . . .” the Acerbic Hand summed up his opinion of “The Lady of Shallot” with the marginal notation: “there never was a more effeminate rotten minded milquetoast… idiot… than plagiarist Tennyson.”

To give him his due, the Acerbic Hand was knowledgeable on the Fenlands, commenting on regional boundaries, history, etymology, the stones of Ely Cathedral, tillage acreage. When I saw that he had put check marks beside the names of more than 250 butterflies I wondered if he had been a lepidopterist or at least a collector who, with happy memories, was ticking off specimens he had captured. It is interesting that the only insects listed in Miller and Skertchly’s compendium are butterflies. There is no mention of mosquitoes, whose link to malaria was not yet known.

Christine Cheater, in her essay “Collectors of Nature’s Curiosities,” described how in England “By the mid-nineteenth century, the pursuit of nature had become a craze.” One of the most extreme examples is that of a wealthy Yorkshire lawyer who had a penchant for beautiful bird eggs. He fixated on the eggs of an unlucky guillemot who nested in the limestone cliffs, and paid someone to collect the eggs from her nest every year, year after year. This bird did not pass along her genes for beautiful eggs.

Some social scientists have seen the nineteenth-century British passion for butterfly collecting as a reflection of the drive to possess an empire. Others see it as nascent scientific methodology. Cheater notes wryly that studies of the period’s collecting fever ascribe it to “the expansion of the British Empire, romanticism, nationalism, the birth of the natural history museum, interior decorating and the activities of commercial enterprises.”

Among the improbably diverse group of collectors there was also the emergent scientist. When he was young Darwin collected beetles and in his autobiography he declared his love:

I give a proof of my zeal: one day, on tearing off some old bark, I saw two rare beetles, and seized one in each hand; then I saw a third and new kind which I could not bear to lose, so that I popped the one which I held in my right hand into my mouth. Alas! It ejected some intensely acrid fluid, which burnt my tongue so that I was forced to spit the beetle out, which was lost, as was the third one.

The depth of a collector’s passion is exemplified in Alfred Russel Wallace’s first glimpse of Ornithoptera croesus, aka the “golden birdwing,” a denizen of damp Indonesian forests. “My heart began to beat violently, the blood rushed to my head, and I felt much more like fainting than I have done when in apprehension of immediate death, I had a headache for the rest of the day.” Vladimir Nabokov described his personal fixation:

“Few things indeed have I known in the way of emotion or appetite, ambition or achievement, that could surpass in richness and strength the excitement of entomological exploration.”

There may be yet another reason for the collectors’ attraction to the iridescent and brightly colored insects. The English were sensitive to vivid hues after the accidental 1856 discovery of aniline dyes. A young genius, William Perkin, loved chemistry. When the precocious youth was eighteen he began to search for a synthetic way to make quinine, the only known treatment for bone-shaking malarial diseases. When he tried coal tar as a base he did not get quinine but only a thick brown sludge.

This too is part of the human psyche—a burning sense of irrevocable loss yoked to a fatalistic acceptance of “progress” and “improvement” and the hubristic idea that “now”—the time in which we live—is superior to all previous times.

Cleaning out his flasks with alcohol he was startled to see the sludge change to an eye-searing magenta. It was the first synthetic dye and he named it Mauveine—a wonderful name perhaps for the heroine of a period novel. The brilliant and intensely saturated magentas, heliotropes, flames, buttercups and malachite greens captivated the fashion world nourished by Britain’s dominant textile industry. It took but a turn of the head and open eyes to start collecting brilliant butterflies.

Even in the last quarter of the nineteenth century when the Acerbic Hand was marking up his copy of Fenland, England was home for a large number of native butterflies, with the fens particularly rich hunting ground.

There was mile after mile of short-cropped downland sheepwalks alive with Adonis and Chalkhill Blues; every parish contained ancient woods managed as coppice with a regular supply of warm, sheltered, flower-filled glades for Fritillaries, White Admirals and Hairstreaks. There were no insecticides, no artificial fertilizers, filling-stations or out-of-town supermarkets. Major roads and highways only infrequently criss-crossed the landscape… Pollution was confined to the larger cities. The patchwork countryside, which since time immemorial had supplied hay and pasture for horses and farm animals, timber and fuel-wood, corn and orchard was also a paradise for insects.

All that changed with fen drainage. Such rarities as the large copper, whose larval food was the great water dock (Rumex hydrolapathum), and the Manchester argus, when deprived of the heath and cottongrass it needed, disappeared. Whittlesey Fen was the large copper’s habitat and when that fen was drained in 1851 the insect was doomed. The swallowtail, which depended on milk parsley plants in sedge fields, was another victim. The piecemeal drainage of the fens over centuries by various “projectors” made fatal problems of fragmentation. No longer were the fens’ many distinct habitats parts of a water-connected whole. The ecologist Ian Rotherham explains how species were lost when the fens were drained.

…in an isolated pocket of habitat, literally an island in an unfavorable sea of farmland, the results are disastrous. Here we see evolution in action. The conditions most favor individuals that do not disperse widely, but which remain in their original breeding site. This may help them survive but it also encourages inbreeding and discourages any wider dispersal to new areas. This appears to be what happened to the swallowtail in the Fens.

When Whittlesey Fen was drained Charles William Dale, the collector son of the famous lepidopterist J. C. Dale, observed: “What was once the home of many a rare bird and insect became first a dry surface of hardened mud, cracked by the sun’s heat into multitudinous fissures, and now scarce yields to any land in England, in the weight of its golden harvest.”

The protestors were the fen people—poor, and considered of low social class. They fought against the drainage “projectors” but were worn down and overcome after centuries of protest. In the seventeenth century the Crown laid its heavy weight on the side of drainage projects. Laws, patents, “rights”—all the machinery of bureaucracy pressed on the fen people. The drainage movement had changed over the years from a few protested local projects to a broad regional movement for drainage that was lamented but accepted.

Here and throughout Skertchly’s Fenland we see the Victorian mindset—while many English people during the final years of draining the fens expressed deeply felt sorrow and loss, in the same breath they praised the crops of wheat and maize that replaced the wild wetlands. I am reminded of the comment of one of the men opening the American west who opined that the defeat of the Indian was “essential albeit tragic.” This too is part of the human psyche—a burning sense of irrevocable loss yoked to a fatalistic acceptance of “progress” and “improvement” and the hubristic idea that “now”—the time in which we live—is superior to all previous times. The proofs given are usually technological “improvements.”

__________________________________

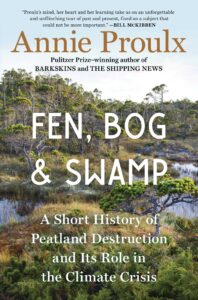

Excerpted from Fen, Bog & Swamp: A Short History of Peatland Destruction and Its Role in the Climate Crisis by Annie Proulx. Copyright © 2022 by Dead Line, Ltd. Excerpted with permission by Scribner, a division of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

Annie Proulx

Annie Proulx is the author of the short-story collections Heart Songs and Other Stories (1988), Close Range: Wyoming Stories (1999), Bad Dirt: Wyoming Stories 2 (2004), and Fine Just the Way It Is: Wyoming Stories 3 (2008), and of the novels Postcards (1992), which won the PEN/Faulkner Award, The Shipping News (1993), which won the Pulitzer Prize and the National Book Award, Accordion Crimes (1996), That Old Ace in the Hole (2002), and Barkskins (2016). Her stories have been reprinted in the 1998, 1999, and 2000 editions of The Best American Short Stories and in the 1998 and 1999 editions of the O. Henry Awards: Prize Stories.