Annie Proulx on Freewheeling

Nature Writer Ellen Meloy

"Some of the essays seem to have been written last week, so fresh are the topics."

Naturalist and environmental writer Ellen Meloy, who died in 2004, loved the huge red rocks of the Four Corners region where Utah, Colorado, New Mexico, and Arizona come together in a dusty knot, a region of Navajo and Hopi languages and cultures with some of the most profound land views in North America.

Her witty, freewheeling essays on the imbalance between humans and nature lightened up the Cassandra genre known as “environmental literature.” Verlyn Klinkenborg, in an obituary remembrance, quoted her as saying that much nature writing “. . . sounds like a cross between a chloroform stupor and a high Mass.”

She had the rare gift of seeing humor in the wild world and in our attempts to know it. She was a master of the telling phrase as when she described her place as “a tiny town in a land that looks like red bones” and commercial airliners as “flying culverts.”

She gave advice about toads: that we should not carry them around and “When you think about licking them, change your mind.” She was curious about all landscapes and told her readers that when they were in new country they should pay attention and “ask why people call their landscape home, what they love or fear, what is blessed, what is destroyed.”

She often urged her readers and listeners to understand their biological addresses, to count the local wildlife, animals, birds, and plants as neighbors. The twitches of weather and climate were important to her and she wanted us to observe and make notes of what was happening in our backyard worlds as William Bartram or Thoreau did. For years in the 1850s Thoreau noted the blossoming times of wild flowers around Concord in his now-famous journals. Today’s scientists used his meticulous data as evidence of climate change.

Several of Meloy’s essays were instant classics. “Lawn” condenses everything into two fierce sentences: “Throw massive amounts of water and petrochemicals on your grassy plot, let it push up from the soil, then cut it down to nubs before it can grow up and have sex and go to seed. A lawn is an endless cycle of doomed ecology.”

“Tourists in the Wild” lampoons New Yorkers lost in the terrifying Great West with a reference to bears, which we all know are spaced about twenty feet apart from the left side of the Rockies to the Pacific Ocean.

But her essays were not all wit and amusement. Some of the essays are less than benign, as “California” with its acid takeoff on the provocative bumper sticker “I’d rather be hunting and gathering” pasted on a luxe-mobile, or “Cracking Up” with its call to “small acts of defiance . . . against a suffocating culture of meaninglessness.” And she could fire off hard truths dipped in sarcasm, as in “Animal News,” which works up from an unnamed man’s statement that wolves should not be reintroduced in the West because, as he says pejoratively, “The wolf kills for a living,” to her point that we are “so estranged” from the lives of wild creatures that we offer them the choice of only living lives that suit us or dropping dead. Humans also are animals, she says—face it.

Some of the essays seem to have been written last week, so fresh are the topics. In November of 1996 Ellen Meloy was utterly sick of election jabber, of the inescapable faces on television and the incessant brainless repetitive rhetoric. “What,” she says, “has become of the honorable and decent public servant? You won’t find one in either political party, so kill your television.” And she turns hers off. One of her best essays, “Bluff,” (below) is about guns. The subject becomes important when “three anti-government extremists” who have killed a policeman in Colorado turn up not far from the Meloy place. Roadblocks, canine units, sheriffs and cops, and SWAT teams are everywhere. Her husband Mark has an old shotgun, but Ellen Meloy, who describes herself as a “token, squishy, white doughball of liberalism who still believed that if you hated government, maybe you should do something really radical to change things, like vote,” does not have a gun. Readers! Let that sink in. She lives in the West, the American West, and does not have a gun! Yet lives to tell about it.

In the end, what we take away from the essays of Ellen Meloy is her impassioned request to us all to regard what is around us. “Pay attention to the weather, to what breaks your heart, to what lifts your heart. Write it down.”

Amen, amen.

–Annie Proulx , Port Townsend, Washington

*

“Bluff”

Perhaps it began with the wind. For weeks, the wind blew its dry burden of red dust down the canyons and across the open desert into our ears, our pockets, our nerves. The wind lifted up the top three inches of Arizona and dropped it on our heads. The gusts made the roots of my hair ache. No one in Bluff could remember so much wind blowing day and night, day after day.

People grew testy and distracted, but we knew our land well. We knew the stillness would return, even as we longed for it. Then one day the wind did stop. The Earth tilted and Bluff slid.

After killing a policeman in nearby Colorado, three anti-government extremists surfaced east of Bluff, where one of them shot and wounded a local deputy. Within hours, the somnolent little town turned into an armed camp with roadblocks, helicopters, SWAT teams, canine tracking units, and hundreds of edgy men in uniform darting madly about with small arsenals on their persons.

Early in the manhunt, my husband Mark and I were allowed through a roadblock late at night. We drove to our isolated house above the river. Where Bluff should have been, there was a blank space, an inky darkness. The entire town had disappeared. No one told us that residents had been evacuated.

From some obscure heap of dust balls, Mark unearthed his old shotgun, put it next to our bed. The damaged gun barrel was unnervingly curved. The label on the ammunition box showed a pleasantly plump pheasant.

As a thudding fleet of choppers passed over us, Mark told me that if I had to use the gun, I should aim for the crotch. “Whose crotch?” I asked, certain that the outlaws were all at once somewhere, anywhere, everywhere. When I took a shower, it felt like the movie Psycho.

The Bluff school, used as a command post, swarmed with troops. The testosterone was so thick a woman could get pregnant just by walking down the hall. The map room was strangely chilly, an oasis of detumescence.

When it was discovered that we had not evacuated, that our isolated property had not been checked, and that I was alone while Mark worked, I was given two sets of advice.

A sheriff’s deputy said, “Get yourself some guns.”

The FBI said, “We’ll give you an escort.” I took the escort.

“Get guns?” I mumbled as five FBI guys led me down my driveway. “Get myself some guns?”

Obviously, I was the only person in North America without them. One token, squishy, white doughball of liberalism who still believed that if you hated government, maybe you should do something really radical to change things, like vote.

I wondered if arms against arms created an endless spin into violence. I wondered why the world had turned so vicious. I wondered why the FBI guys wore bulletproof vests and I did not.

They poised their rifles as we reached the house and, with quiet courtesy, asked me for permission to enter.

I stood outside in a limp noodle posture, my wildlife menagerie around me—lizards, rabbits, ravens, the bull snake that napped under the mint bushes, the flycatcher and her nest of baby birds in our eave. I looked through the glass doors at the way too many books, my stupid little piles of river rocks, the fetishes from Mexico, the Navajo mud toys.

The armed search precipitated a wholesale destruction of the lyrical. It felt dreamy and unreal, like hand grenades in a monastery.

These days, people still recount manhunt anecdotes. They recall the endless rumors, such as the one about the outlaws hijacking a UPS truck and terrorizing the Four Corners region in little brown suits.

Countless stories are told, all but the most critical one. That is, what really happened and why did these men disrupt so many lives with their survivalist fantasy, one that arms itself to the teeth and touts violence as a virtue?

Two of the fugitives remain at large. They will likely surface when they become bold or miss their mommies. Meanwhile, people in Bluff slowly reclaim the river and de-spook their yards, trails, and canyons. I look at my neighbors’ faces and see a bone-deep fatigue.

The wind has returned. It comes up every afternoon, pushing heat and dust, rattling the dry cottonwood leaves and thrashing my hair about my face. We long for stillness.

This time, no one is sure that it will come again so easily. In Bluff’s deep peace, there is a severe crack.

July 24, 1998

*

Ellen Meloy was a native of the West and lived in California, Montana, and Utah. Her book The Anthropology of Turquoise (2002) was a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize and won the Utah Book Award. She is also the author of Raven’s Exile: A Season on the Green River (1994), The Last Cheater’s Waltz: Beauty and Violence in the Desert Southwest (2001), and Eating Stone: Imagination and the Loss of the Wild (2005). Meloy spent most of her life in wild, remote places; at the time of her sudden death in November 2004 (three months after completing Eating Stone, she and her husband were living in southern Utah.

__________________________________

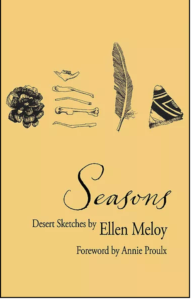

From Seasons: Desert Sketches. Used with permission of Torrey House Press, in partnership with RadioWest. Copyright © 2019 by Ellen Meloy. Foreword copyright 2019 by Annie Proulx.

Annie Proulx

Annie Proulx is the author of the short-story collections Heart Songs and Other Stories (1988), Close Range: Wyoming Stories (1999), Bad Dirt: Wyoming Stories 2 (2004), and Fine Just the Way It Is: Wyoming Stories 3 (2008), and of the novels Postcards (1992), which won the PEN/Faulkner Award, The Shipping News (1993), which won the Pulitzer Prize and the National Book Award, Accordion Crimes (1996), That Old Ace in the Hole (2002), and Barkskins (2016). Her stories have been reprinted in the 1998, 1999, and 2000 editions of The Best American Short Stories and in the 1998 and 1999 editions of the O. Henry Awards: Prize Stories.