Friday

Ruth was just out the door for her speaking engagement at the local high school, laptop bag over her shoulder, when the delivery truck pulled into her driveway. She paused with a hand on the knob, fresh fall Minnesota air filling her lungs, watching as the man in brown shorts approached.

She wasn’t expecting a package—was she? Hope was dangerous, but she couldn’t hold back a smile as he handed over the box.

“Something good?” he asked.

“Possibly.”

Taking it, she noted the Vermont return address and heard the soft slide and thud of what could be a rare journal, more than a century old and certainly improperly packed. But she wasn’t about to rebuke the sender. Not when he was trusting her with this, Annie Oakley’s own words, unknown to any scholar.

The sharpshooter had left behind an unfinished autobiography and some everyday correspondence when she’d died in 1926, but little else of substance written in her own hand.

Ruth’s last email exchange with an antique collector who called himself Nieman had ended inconclusively. He’d agreed to send her a few scans or mail select photocopies on the condition that she understood he was in a hurry, with a large-scale purchase planned pending the journal’s authenticity. She promised to take a look, despite his refusal to provide any details on how the item had come into his possession.

Context matters, she had replied. The more you withhold, the less reliable my analysis will be. Also please keep in mind that an original provides much more information than a photocopy. I’ll work pro bono; that isn’t the issue. But I can’t do much without quality source materials.

The journal was only the first step. Nieman had gotten a glimpse of a letter and wanted to purchase an entire set of rare correspondence, all of it somehow related to the journal in terms of content, about which he had offered only meager clues.

Your call, she’d responded, trying to play it cool. I have some time this week. Next month is busier.

The sharpshooter had left behind an unfinished autobiography and some everyday correspondence when she’d died in 1926, but little else of substance written in her own hand.It was a lie. Aside from the speech she was giving to a history class in thirty minutes—make that twenty—Ruth had nothing scheduled for the rest of the year, aside from trips to the chiropractor and putting her house up for sale.

Watching the truck back out, Ruth tried not to wish or want too much. She ran a hand through the curled ends of her auburn hair—styled, for once—trying to prolong this feeling of well-being. She was wearing a corduroy jacket she’d ordered online and her luckiest blue-stitched cowboy boots. She’d removed the knee brace she normally wore under baggy sweatpants in order to squeeze into jeans she hadn’t bothered to take out of a drawer for months. She felt the warm sun on her face and smelled burning leaves.

History is well and good, but the present is worth noticing, too. Remember this. For a few lovely seconds, time didn’t matter.

But as soon as the delivery truck was out of view, it mattered again. No time to slice through the layers of fibrous brown packing tape. Definitely no time to make sense of journal entries. She should be able to summon some patience, considering she’d been stuck with no new leads for several years.

Ruth unlocked the door and hurried to the kitchen counter, planning to leave the box there. Then she spotted the kitchen scissors, sticking out from her jar of wooden spoons.

Just a peek.

She ran the point of the scissors down the flap and pulled. Inside she saw bubble wrap. Bubble wrap! Nieman should have known better. Through the plastic she saw a color: burgundy edged with dark brown. The real thing. Not a set of photocopies. She wouldn’t have taken the risk, but he had, and bless him for it.

Her fingers reached to pull the wrapped journal out of the box, but then she caught sight of her watch. She was due in Holloway’s class at 2:05. The walk, about three-quarters of a mile from the end of her road, down a trail and to the back entrance of the public school, took a fit, healthy person fifteen minutes. For Ruth, it would be twice as long.

She felt her stomach flutter with joy at what she’d received, overlaid by nerves about being late. She shouldn’t have opened the box, but she was too excited to feel any regret. She reached into the ceramic dish next to her mail basket, grabbed the key to her Honda Fit and proceeded through the garage door before reason could stop her.

Door open, laptop bag on the passenger seat, thumb drive with her slideshow ready as backup in case her own computer was wonky and it was easier to use Holloway’s. Garage door up. Seatbelt. Key in the ignition.

Maybe today. It had to happen sometime. Why else had she put off selling the car, once she’d broken up with Scott and had no one else to drive or even halfheartedly maintain it?

Because you’re going to want to drive again. You’re going to be ready at some point.

The hatchback didn’t look anything like the small Subaru sedan she’d smashed up. This was new and bigger, silver, ridiculously clean. Well, of course it was clean. It had less than fifty miles on it.

But as soon as the delivery truck was out of view, it mattered again.Her hand gripped the gearshift without taking it out of park. She touched her toe to the gas pedal just to feel the positioning—no surprises—then placed the slippery bottom of the boot squarely against the brake. Quick glance at all mirrors. Another squeeze, preparing to shift into drive. Out on the dead-end road, there wasn’t a single car or pedestrian to worry about. Look forward. Look right, even though there were only woods that way; still, there could be cyclists or walkers coming from the trail. Look left. Right one last time.

Ready.

Then she saw it all at once. New Year’s Day. The bridge, the car with its hungover driver braking too fast on the icy road ahead of her, the guardrail.

She knew what would come next—the vision, terror-fed illusion, whatever it had been. She couldn’t let her mind go there, or her body would follow into a full panic attack.

Heart in her throat, Ruth yanked her foot off the pedal and her hand off the gear shift.

“Oh, god,” she sputtered.

She took a deep breath as her mind slammed that door shut just in time. She fumbled with the seatbelt, hands shaking, desperate to be free of the strap. She would move slowly, tricking her body into a state of calm. She would gather up her things and exit the garage without drama. She swallowed and inhaled again. As she opened the door, she checked her watch. Ten minutes to two.

Now you’ve done it.

At the school, Ruth hurried toward the metal detector, eyes focused on the yellow banner beyond: we love our visitors / horizon high. But the seated security guard called her back.

“Quick look at your ID and you’ll be on your way.”

“I don’t have anything on me.”

She took a deep breath as her mind slammed that door shut just in time. She fumbled with the seatbelt, hands shaking, desperate to be free of the strap.“You don’t have a faculty ID?”

“I’m not faculty.”

“But I’ve seen you around here, haven’t I?”

“My fiancé teaches here.” She’d barely spoken the words before regretting them. Scott wasn’t her fiancé anymore. It just slipped out sometimes.

“Another official ID from this list, then. You can’t enter the school without one of these. Plus, you have to sign the visitors log.”

She hadn’t brought anything except her laptop and keys. In her flustered state leaving the garage, she’d forgotten her purse.

Past the security station, classroom doors opened and teenagers spilled out, the halls echoing with squeaky footfalls.

“I’m running out of time,” Ruth said. “Is there something we can do?”

From the corner of her eye she noticed a student, maybe sixteen or seventeen, standing behind her: dark hair, tall. Skinny jeans and a collared plaid layered over a graphic T-shirt, jacket hanging from one hand. The guard gestured for him to go around Ruth and show his school ID, but the boy remained where he was.

“That’s okay,” the boy said. “I’m not in a hurry.”

“Oh, sure.” The guard laughed. “You just want an excuse to be late for class. Tell ’em you were stuck behind a terrorist.” He added for Ruth’s benefit, “This isn’t the airport. We can make jokes.”

“But you can’t make exceptions.”

“No, ma’am.”

So she was not only late, but apparently a “ma’am” at thirty-two. Wonderful.

Ruth asked, “Can you at least get a message to Mrs. Holloway for me?”

Making no move to rise from his chair, he gestured back outside. “Main visitor center. South side. Past lots B and C, then swing a left past the bus zone. Guard there can send someone to hand-deliver a note, but she probably won’t see it till end of the day.”

From the corner of her eye she noticed a student, maybe sixteen or seventeen, standing behind her: dark hair, tall.At the beginning of the year, she’d given herself until December 31st to make a professional appearance—anywhere. When Jane Holloway issued the invitation in September, Ruth knew this was the easiest way to finally check one item off her Rehab Resolution List. Someday she’d work outside the house again, and the last two years, terrible as they were, would be sealed away, moved into deep archival storage.

But that was someday. For now, she’d settle for much less: just one good, purposeful, dignified hour.

From among the scattered students still milling around, pocketing gadgets or fumbling with backpacks, a familiar figure emerged.

“Scott!” she called out. “They won’t let me in.”

He paused, squinting. New sweater, same old glasses.

“Jane Holloway’s looking for you.”

“I know. I left my wallet at home. I don’t suppose you could vouch for me? All this new security . . .”

“Tell me about it.” He approached, calling to the boy in line behind her. “Reece, get going. You’re late for your next class. And hey, you weren’t in calculus.”

The boy slid his school ID out of a tight back pocket and handed it to the guard. “Did I miss anything?”

Scott’s most detested question, Ruth remembered.

“Did you miss anything? Oh, no—we were just hanging out. Besides the quiz and the chapter review.” He turned to Ruth. “I’ll send someone to tell Holloway you’ve got a hitch. And Ruth—sorry. I’d drive you to your house if I could, but my own class is starting. You can take the shortcut, right? Ten-minute walk?”

Reece was still lingering, fists crammed into his tight pockets. “I’ve got a car.”

“That’s all right,” said Ruth.

“No, really. I can drive you.”

She glanced at her watch. “It’s okay. You get to class.”

“It’s, what, three minutes by car?”

Surely he couldn’t just leave campus without permission.

“That doesn’t seem . . . weird to you?”

From among the scattered students still milling around, pocketing gadgets or fumbling with backpacks, a familiar figure emerged.“Weird is good,” he said.

Scott frowned at Reece and gestured toward Ruth’s laptop. “Do you have a scanned ID in your files? Passport, maybe? I might have put that in a folder for you when we were . . .”

Planning to go on vacation. Thailand or Vietnam, they’d never decided.

“Maybe. It takes about ten minutes just to boot this thing up.”

“Ten minutes?” Reece said. “That’s messed up.”

Scott shook his head. “He’s right. You’ve got to get that into the shop.”

“Defrag it, at least,” Reece said. “Free up some space on your hard drive.”

“You’re both right.” The computer shop was fifteen miles away, not on any bus route from this side of town. Nothing was easy or quick these days. “I’ll get to the mall this weekend.”

Scott must have heard the catch in her voice. “Reece here could do it for you, after school. Hire him for a house call. He’s a whiz at that stuff.”

“I don’t know—” she started to say, but Scott wasn’t listening.

“Reece, you know the cul-de-sac on Pine Street, behind the school? She lives in the A-frame.”

“All right, all right,” Ruth said, in a tone that meant, Stop. It’s my life now. You were liberated from the landscaping and recycling and laptop fixing. Maybe he was trying to reconnect. Still, this wasn’t his problem. It wasn’t appropriate for him to give out her address, though she hadn’t objected last spring when he’d sent over a pair of students who mowed lawns and cleaned windows.

“Scott, thank you for your concern. You should get to your class. And Reece, nice to meet you, but you’re late, too.”

“Holloway’s my last period,” Reece said. “I can tell her they won’t let you in.”

Resigned, Ruth took a deep breath and really looked at the teenager standing on her side of the guard’s station, refusing to walk through. “That would be a big help. Thanks.”

He was six inches taller than her, long arms jutting out of rolled-up flannel sleeves. There was a black infinity symbol on his forearm. Maybe a real tattoo, or maybe just a temporary pen-inked doodle.

She spotted it and, for a moment, couldn’t look away. So familiar.

The nape of her neck tingled. She didn’t know this kid, but she’d just had the sudden urge to step forward, lean in, tell him something. Something important. Thankfully, she stopped herself. But what had she wanted to say?

Blink, she told herself. Blink and breathe.

Maybe seeing her ex again was a bad idea, as Dr. Susan, her first therapist, had said. Running into him could’ve tripped some switch in her brain, even though she was nearly mended now: stable, rational, mostly delusion-free. Or maybe this was just the price for having sat behind the wheel of a car. Or for having gotten too worked up about the journal.

Hell, maybe it was all three, too much adrenaline filtered through an injured brain slowly remolding itself—a process that could take years, all the doctors said. She recorded every incident and setback on her kitchen calendar. Full-on, visually detailed attacks, plus the lesser surges of anxiety. Ripples emanating from a distant splash.

“You okay?” the boy asked. “You look dizzy.”

Without thinking, she took a step toward him to see if he smelled familiar; he did. But it was only stale cigarette smoke and a hint of deodorant spray. Most teenage boys smelled like that.

He was six inches taller than her, long arms jutting out of rolled-up flannel sleeves. There was a black infinity symbol on his forearm.She was tempted to say, Don’t smoke, but that was none of her business. What she actually wanted to say was, I thought you’d quit. That made even less sense.

“No, I’m fine. You should get going. Thanks for telling Mrs. Holloway for me. I’m heading home and will come right back, but the class will be halfway over by then. Can you give her this, so she can have the slideshow up and ready?”

Reece took the thumb drive, nodded and started down the hallway until he was side by side with Scott. Then he swung around and walked backwards. “So, should I come fix your laptop later, then?”

Scott looked back over his shoulder, also awaiting her response.

It wasn’t so much that she wanted to please the man she’d almost married and then lost. She just wanted to reassure him and, more important, herself, that she was okay now. Not afraid or obsessed or stuck, not imagining things, not falling apart. All that was over.

“That would be fine,” she said. “Anytime.”

__________________________________

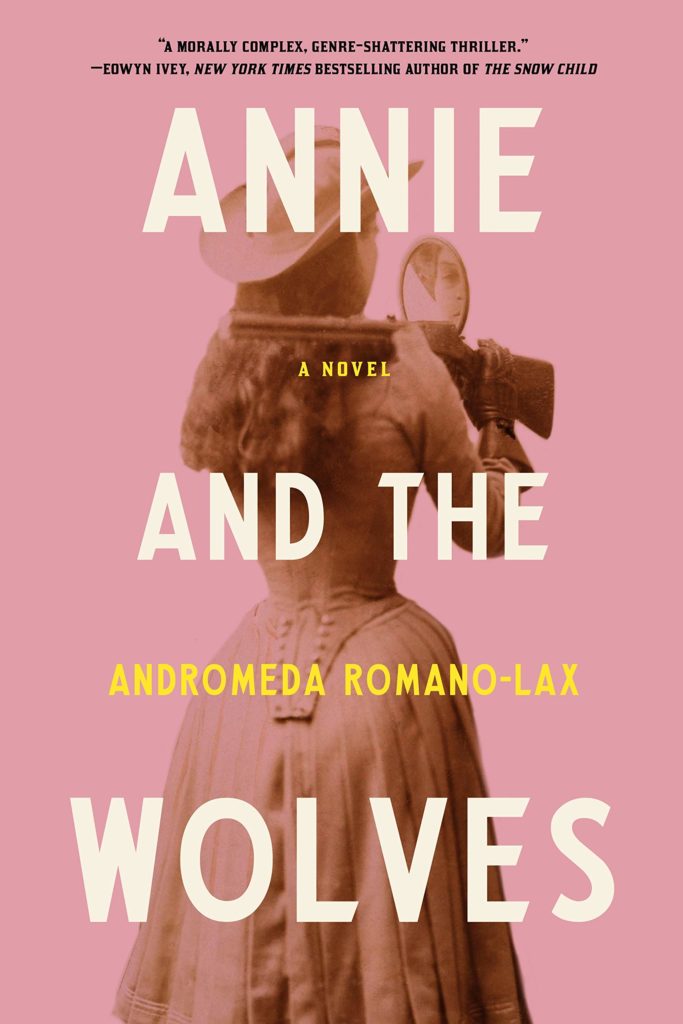

Excerpted from Annie and the Wolves by Andromeda Romano-Lax. Excerpted with the permission of Soho Press. Copyright © 2021 by Andromeda Romano-Lax.