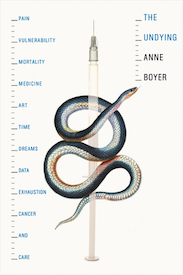

Anne Boyer: What is the Language of Pain?

An Ugly Gathering of Adjectives

To be a minor person in great pain at this point in history is to be a person who feels inside their body when most people just want to look.

There’s expository pain like an X-ray machine, illuminating the difficult mysteries of the interior. There’s the pain that becomes metaphor and there’s the pain that’s read as if it’s the canon. Then there’s trash pain—the libertine pain of malingering, which is more like a texture than an image. Then there’s the epic pain of a cure.

If this were a work of philosophy, I would argue that the spectacle of pain is what keeps us from understanding it, that what we see of pain is inadequate to what we can know, that a problem with understanding pain at this point in history is the generalizing effect and market saturation of vision, but I am 1) not a philosopher and 2) don’t really know.

My pain’s naked grammar was:

how doe sone go on like htis the days gone finally in a way that can’t be though I have a light on my face to hceer me and I took an advicl will take more take vitamin d fake every sunlight the world on fire last night while I slept in such rgitheous pain

True/False:

1. As pain incapacitates a person, it also incapacitates the

2. Pain is an ugly gathering of adjectives

3. Any word for pain is always in a language we cannot yet understand.

A widely held notion about pain seems to be that it “destroys language.” But pain doesn’t destroy language: it changes it. What is difficult is not impossible. That English lacks an adequate lexicon for all that hurts doesn’t mean it always will, just that the poets and marketplaces that have invented our dictionaries have not—when it comes to suffering—done the necessary work.

If pain were silent and hidden, there would be no incentive for its infliction.Suppose for a moment the claims about pain’s ineffability are historically specific and ideological, that pain is widely declared inarticulate for the reason that we are not supposed to share a language for how we really feel.

An example of this assertion about the ineffability of pain is found in Hannah Arendt’s The Human Condition, in which she describes pain as “the most private and least communicable” of all experience. She goes on to write that pain is “the true borderline experience between life as ‘being among men’ . . . and death,” claiming that its subjectivity is so intense that pain has no appearance. Contrast this philosophical truism about pain’s lack of communicability with your own experience of witnessing another living creature in pain. The howls, cries, screams, shrieks, and whimpers of another in pain are unequivocal. The words “that hurts!” or “I am in pain” or “that burns” or “this aches,” and various exclamations like “ow!” and “ouch!” and “motherfucker!” are also generally undeniable communications of pain. A dog or cat in pain is equally communicative. The look of a face in pain—even a non-human face—cannot be mistaken for a look of contentment. Winces, agonized expressions, leaking tears, and gnashed teeth are so communicative, for example, that “a pained expression” is a common turn of phrase.

The drive to stop the pain of others because pain is so loud, so vividly expressed, often takes the form of wanting to do anything at all to end the pain of another precisely because of the way that this pain inflicts the experience of an impossible-to-bear sympathetic discomfort—sometimes in the form of annoyance, sometimes in the form of anxiety, sometimes in the form of pity—upon one’s self. This drive to end the immediate pain of another creature in one’s own proximity is so strong that it can sometimes compel the witness to pain to inflict greater pain upon the sufferer, as when adults threaten to give children “something to cry about” in order to make them quiet. Pain is so communicative, in fact, that the source of much violence could well be found in reaction to pain’s hyperexpressivity. It is the clearness of pain that gives sadists their reward. If pain were silent and hidden, there would be no incentive for its infliction. Pain, indeed, is a condition that creates excessive appearance. Pain is a fluorescent feeling.

That pain is incommunicable is a lie in the face of the near-constant, trans-species, and universal communicability of pain. So the question, finally, is not whether pain has a voice or appearance: the question is whether those people who insist that it does not are interested in what pain has to say, and whose bodies are doing the talking. Jean-Jacques Rousseau, who believed that “commiseration must be so much the more energetic, the more intimately the animal” part of human nature, theorized that a lack of response to those in pain is a characteristic unique to philosophers. “It is philosophy,” he writes in A Dis course Upon the Origin and the Foundation of Equality, “that destroys [a person’s] communications with other men; it is in consequence of her dictates that he mutters to himself at the sight of another in distress, ‘You may perish for aught I care, nothing can hurt me.’ Nothing less than those evils, which threaten the whole species, can disturb the calm sleep of the philosopher.”

On the Internet, pain is a series of bulletin board posts about hermeneutics and time.

____________________________________

Excerpted from The Undying by Anne Boyer. Published by Farrar, Straus and Giroux, September 17th 2019. Copyright © 2019 by Anne Boyer. All right reserved.