Anna Solomon on Overcoming Her Inner Editor While Writing

"The trouble is, my editor self knows a lot more than she used to."

This first appeared in Lit Hub’s Craft of Writing newsletter—sign up here.

When I teach, I talk with my students about gaining control. I mean control over the choices we make as fiction writers: an understanding of the effect one word or structure or rhythm makes over another; the ability to manipulate our readers through mastery of our craft.

But lately, words like mastery and control feel suspect, even dangerous, when it comes to writing — or to much of anything, really. On every level, this time we’re living through has forced me to face how little I know, how flimsy my supposed plans are, and how weak my capacity to predict let alone influence just about… anything.

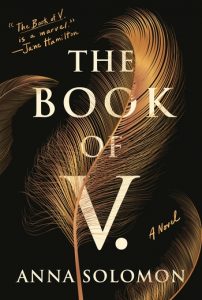

I’ve set aside three novels in the past year, when my third book, The Book of V., was published. Each time, I blamed something different. First, a thematic dilemma: what does this story idea have to do with reality anymore? Next, a logistical one: why bother outlining a novel if I might never again have a quiet moment in which to write it? Then, the more existential: why bother?

My guess is that nearly every writer asked some version of these questions in the past year. What I’m realizing, though, as we emerge from acute crisis, is that there’s a far more useful question, a question of craft, that I’ve really been coming up against each time I’ve abandoned a book. Which is this: now that I’ve written three novels, I’m able more quickly to identify the problems in a given work-in-progress, whether of plot or character or time or structure. But does that ability — that mastery, that control — actually serve me as I write?

To be clear, I’m talking here about first draft writing, the writing I’ve come to think of, unoriginally, as drafting. Drafting works for me because it calls up a physical task, a sketch, a work in pencil; it calls on my creator self, as opposed to my editor self. It’s impossible to come up with a better image than the evil censor mice Anne Lamott puts in a jar and shoots, so I won’t try. The mice are what I want to keep away as I draft.

The trouble is, my editor self knows a lot more than she used to. My creator self is humming along in a scene in which one woman is helping another woman deliver a baby on a kitchen floor, and my editor busts in. Shouldn’t this scene be summarized, after the fact? Why are you writing it from her point of view? Is it even necessary, plot-wise? My god, why are you going into a full page of backstory here? You may think you’re heightening the suspense through delay but really you’re just deflating the scene, shoving the reader out of it. Don’t you know better than that?

I do know better. But that doesn’t necessarily help, for two reasons.

First, even the most impressive knowledge of craft doesn’t make a writer a fortune-teller. The structures I’ve studied, the techniques I’ve applied, the experiments in point-of-view I’ve undertaken… none have met my new characters, not to mention the writer I am now. For The Book of V., I rewrote one chapter at least 20 times, from scratch, before realizing its only value was to convey a single, if critical, piece of information and that I could combine it with another currently pointless chapter and create one totally necessary scene that forced my characters into the dramatic convergence the book turned out to need. Sure, it would have been nice to rewrite those chapters fewer times. But that kind of discovery can’t be replaced by mastery. The only way to get there is to write.

Second, when an attitude of mastery enters the writing process too early, it can be paralyzing. See my creator-interrupting editor above. See, also above, my three abandoned novels. Those stories may have been ill-conceived — but I may also have given up too soon, allowing problems I would not even have recognized earlier in my writing life to overwhelm me, rather than trusting that I would solve them in later drafts.

Trust came easily when I wrote my first novel. I knew so little that it was my only option.

How to regain that trust? In a way, I think the same global chaos that turned my life and productivity upside down has also pointed the way, in that it’s forced me to cede control. I fought hard. But I’m glad I lost. I’ve learned something no book or teacher could teach me: that my life and my work require not only discipline and technique but vulnerability. I’m finally — I think — committed to the book I’m writing now. Not only have I shaken off my editor self, I’ve shaken up core elements of my process, too. For instance, I’m currently writing various chapters without knowing where or in what order they’ll appear in the book, a method (or lack thereof?) that may sound mundane to another writer but that to me felt at first like a kind of sacrilege. A former student astutely pointed out that this may help me further trick the editor into staying away; if she can’t even see a structure, how can she try to fix it?

I often feel afraid. But I’m writing in a fluid, alive way for the first time in over a year. And along with trusting the work, I’m working to trust that my editor self will be there when I need her. I’m proud of how hard she’s worked to learn what she knows. She’ll tear this thing to pieces when it’s time. For now, I pretend to know nothing, and write.

*

Read more on taking risks in writing:

Amy Jo Burns on writing in a new genre.

Maria Mutch on letting go of a plan.

Hannah Seidlitz on Jayson Greene and writing about grief.

Ysabelle Cheung on narrative and fragmentation.

*

4 Books That Capture a Spirit of Risk-Taking

RECOMMENDED BY ANNA SOLOMON

Min Jin Lee, Pachinko

Edward P. Jones, The Known World

Marilyn French, The Women’s Room

Elizabeth Graver, The End of the Point

__________________________________

The Book of V. is available via Henry Holt & Company.

Anna Solomon

Anna Solomon is the author of The Book of V., Leaving Lucy Pear and The Little Bride and a two-time winner of the Pushcart Prize. Her short fiction and essays have appeared in publications including The New York Times Magazine, One Story, Ploughshares, Slate, and more. Coeditor with Eleanor Henderson of Labor Day: True Birth Stories by Today’s Best Women Writers, Solomon was born and raised in Gloucester, Massachusetts, and lives in Brooklyn with her husband and two children.