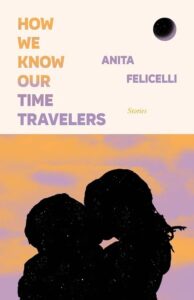

Anita Felicelli on Crafting a Collection of Existential Speculative Short Stories

Jane Ciabattari Talks to the Author of "How We Know Our Time Travelers"

Anita Felicelli’s new story collection opens with a tsunami bearing down on a drought-stricken California coast, with two friends ready to party despite the incoming danger. “On the night of the big wave, we ignore the warnings blowing up our phones and stay on the beach. It’s Violet’s idea, of course it is. Whether we’re smoking weed at midnight in the yellow sour grass by the gas station or drinking Kahlua and ice cream shakes on the clock or skimming money off the top of the cash register at work, it’s always Violet’s idea to break rules.”

“Until the Seas Rise” is a brilliant opening to a set of speculative stories distinguished by surreal experiences, emotional disconnection, external disruption, and a steady stream of time-traveling paradoxes. Our email conversation took place during an atmospheric river that brought more than a foot of rain to Northern California. This, after a summer of record heat. A reminder that, as in How We Know Our Time Travelers, the reality of the universe sets the stage for the imagination to do its work.

*

Jane Ciabattari: How did the pandemic and ensuing years of turmoil affect your life, your work, the writing and launch of this new story collection?

Anita Felicelli: My life was upended entirely with the pandemic, when it began in 2020. I’m on immunosuppressants, so I became particularly isolated from those outside my immediate family for two years in order to avoid contracting Covid-19. At that time, I had been working around seventy hours a week for many clients, and I struggled to get the same amount of work done while parenting three small children around the clock. The stress exacerbated certain medical conditions—I collapsed and had to be hospitalized that May, and the despair only continued with wildfires that fall and the run up to the election of 2020. It felt like we were living through a kind of apocalypse, end times—or that I was at the end of everything, anyway, and my feeling of being obliterated led to the stories “Steam Tunnels,” “Assembly Line,” “Mother, My Monster,” “Amrita,” “A Minor Disturbance.”

There’s so much we’re unable to see about each other, and about the world, and in that space of not seeing…there’s the potential for anything to happen.

When Biden won, however, I thought we might not have to watch the world die so rapidly. I set the collection aside in favor of finishing a family saga about memory and technology and starting another novel. But four years later, the launch of How We Know Our Time Travelers finds me in a much different, more even-keel place, despite the state of the world; starting last spring I began to work set hours as an editor, and since I’m not in survival mode currently, I now take only select freelance clients and projects for the weekends.

JC: When did this collection begin to take form? How long did it take to complete? What was your inspiration?

AF: In retrospect, I’ve always been writing fiction about time and reality—both of those themes show up in my work time and again, because I’m so conscious of how one bends the other. For the first quarter of my life, time felt stretchy, like a bag I could stuff more into. In line with many other parents, however, once I had children, I felt differently—we seemed to be hurtling through time so fast I could barely breathe. How could I prolong my time with them? I became interested in anything that could alter and slow my perception of time to be here now.

As for inspiration, sometimes my writing responds to my earlier writing. I have a kind of contrarian risk-taking tendency where my mind seems to be in a constant argument with itself: Ok, you’ve already done that, now can you do the opposite? In 2019, I wrote the straightforward story “The Encroachment of Waking Life,” an unabashed time travel story to a dystopian future by means of an external technology (a plane). But in 2020, as if arguing against that more obvious form of time travel, I wrote the title story of this collection, in which time travel is always happening internally, organically, within one’s own mind. We’re constantly being carried back by sense impressions, similarities, our mind’s quirks.

Once I noticed my time-reality obsession in several stories I’d been writing, I began styling the collection around that. The collection took around four years from writing “Until the Seas Rise” to WTAW Press’s editing and publication of the manuscript to complete.

JC: What was the evolutionary path of your title story?

AF: A number of my stories grow out of altered neurological sensations that started in 2018 or 2019. One was a heightened, almost overpowering sensation of déjà vu that can randomly attach to situations even when there is little to prompt it. Fascinated by those alterations to my experience of living in my body, I found myself conjuring a story about what would happen if another version of myself, the visual artist I’d been back in my younger years, had been allowed to get old and experienced this sensation but treated it as a real thing, believed the cause was time travel. Once the story sufficiently articulated itself to me that winter, I typed it up in one go; it felt like the unnamed narrator’s voice used my body as a medium.

JC: Which was the first story you wrote? The last?

AF: Looking through my emails, I realize that an old version of “The Night the Movers Came”—weird flash fiction exclusively focused on a hallucination and not the reality that surrounded the woman having it—was written in fall 2014. I had forgotten. However, the first story I remember writing in its entirety, was “Until the Seas Rise,” which came to me when I was walking around alone on the beach as the sun set over the ocean at a Tin House winter workshop in Newport, Oregon, and thinking about Davenport Beach in the Bay Area where we’d gone for senior cut day in high school.

The last story I wrote was “A Minor Disturbance,” which is about a religious mother who comes to believe that an unseen squatter has taken up residence in her house’s spare bedroom. It was drafted as a kind of a supernatural locked room or poltergeist story, shortly before the 2020 election, a time when I was afraid that other Americans would vote us into a dictatorship. Perhaps, I was subconsciously allegorizing what was my greatest fear in October 2020—that the president would never voluntarily exit the White House, would just stay and stay. This only occurs to me now, in retrospect, answering this question—I don’t intend to write allegories, but they seem to happen. Thanks for prompting me to think about that, Jane.

JC: How did you decide the order of the stories? How long did that take?

AF: I rearranged the stories multiple times over the course of four years, but my editor suggested the final order in the book that you see now. There were certain subtle elements I wanted to play with when ordering the stories. For instance, I wanted to start somewhere in a dystopic future but move to a less harrowing past—I wanted us to travel backward to a moment of hope. The first apocalyptic story, “Until the Seas Rise” is set at one outer point in the future, and glimpses of that devastated landscape recur throughout the book. But the end of the world—as the collection envisions—it is not always an external event. In certain stories, it emerges in an inner landscape, as in “The Night the Movers Came,” narrated by an old woman; the last story takes readers way back into her days as a woman in her twenties at the start of her career. Similarly, once I first wrote the titular characters in one of the later stories, “The Fog Catchers,” it felt like they should have an increasing presence from start to finish in the collection, and I seeded that in revisions.

JC: “The Fog Catchers” is narrated from the point of view of Viduna, a crafty woman at a beachside resort on the Central Coast of California who encounters a group of people filling bottles with fog to sell, and meets Dariush, a man she sees as a potential lover, a potential mark. After he is murdered (she wonders if she did it while in a Klonopin haze) she is “filled with longing for another timeline.” What was the seed for this story?

AF: I’m fascinated by con artists, not so much with the specifics of their crimes, but their skills and tactics of persuasion—it probably grows out my interest in performance and method acting and how realities are made. In my first collection, Love Songs for a Lost Continent, I’d written the story of Leda, a young female hitchhiker, something of a shapeshifter, who learns the art of a con from a seasoned grifter, a man. For years after, I longed to counter that story about a protege with another about one about a hardhearted femme fatale, someone to whom it would be more difficult for me to relate—Viduna. I feel freest when I write characters drastically different from myself.

I wrote “The Fog Catchers” after a trip to Big Sur, where it happened to be foggy, and I realized that at night, wandering around the cliffs on the coast, it can be as sinister there as it is in urban areas, even if the atmosphere is different. The wilderness offers the possibility of evacuating your real self, a possibility that is conducive to making stories. There’s so much we’re unable to see about each other, and about the world, and in that space of not seeing, of being in fog, there’s the potential for anything to happen. I love Golden Age noir films where the spotlight is not merely on a detective but on a perpetrator, like Jacques Tourneur’s Out of the Past.

JC: In this collection you present the end of the world as we know it as if offhandedly, through time machines, holograms of dead families, the clay boy a woman sculpts to fill a vacuum in her life who animates for a brief time, the Monster that burrows into a mother’s brain, triggering “a sleep roll of fatigue, a fog tolling into every lit recess of Mother’s mind, turning it dark,” a woman writing a friend from a psychiatric facility to describe the elixir of immortality she is working on. What feeds this vision of a universe soaked in what novelist Joshua Mohr calls “existential dystopia”?

AF: For someone who has lived a little less than half of a century, I suffer what feels like an inordinate amount with a medical condition, and new symptoms that began around 2018. Mortality began stepping on my neck in every decision I made; it took years for that to become a clarifying force, but I was in the thick of mourning the loss of myself, while writing this book. No doubt, it’s living intensely inside this particular, multiply divergent and hampered body that most sustains my feeling that meaning is not born from empirical reality, or realistic perspectives, but inside the self and limitless possibilities of imagination.

My vision is fed by a high-low postmodernist sensibility born of growing up absorbing folklore, comic books, sci fi, quest narratives, horror novels, detective novels, in addition to a slew of realistic nineteenth-early twentieth-century novels, mostly British, continental philosophy, and French symbolist/surrealist poetry. I was a very open reader from the start, susceptible to abandoning myself entirely to an array of discordant stories, and still am, much to my chagrin. But it was rare for me to go all in for the stories that fall in the middle of a conventionally conceived high-low art spectrum.

I studied continental philosophy in college, alongside art and British literature. The philosopher Søren Kierkegaard wrote about existential anxiety, not as a species of fear, but as a dizziness of freedom and infinite possibility that was necessary for creative work. In a world where meaning isn’t imposed from outside authorities like God or the government, but from something we conjure from within, we rely on ourselves to make meaning. I think it’s my anxiety in that existentialist sense of a vertigo of potential choices, that tinges the universe of this book.

With regard to what I said about my own suffering—when you look at human history more broadly, the entire amount of suffering humans have experienced is mindboggling. Wars, invasions, totalitarianism, plague, death, trauma, madness, and more death. And yet, here we are, continuing to face emotionally challenging problems, but we are able to choose, even if only slantwise, what our experiences mean to us and make art, write stories. The word “utopia” comes from the Greek for “no place,” and “dystopia” means “bad no place” which seems about right for the present and future where I set these stories. But even in a dystopian story, there are possibilities; As a writer, we can think about how constrained a character is by the government or physical conditions or community and group behavior as part of creating bold, complex characters.

I think it’s my anxiety in that existentialist sense of a vertigo of potential choices, that tinges the universe of this book.

JC: How are you able to balance your writing life with your life as a book critic, editor of Alta Journal’s California Book Club, former board member (and fiction chair) of the National Book Critics Circle?

AF: When you set it out directly like that, I have no idea—sounds like someone else. But I used to have two herding dogs, and they would get so bored, they’d start chewing on whatever was available, even their paws. They needed the constant mental stimulation of hard work. They needed puzzles to solve and humans or other animals to herd—maybe I take after them.

Many of the people I’ve admired and modeled my writing life after, seem to have moved fluidly between multiple roles involving books: Toni Morrison, Virginia Woolf, D.H. Lawrence, Francine Prose, Jean-Paul Sartre, Susan Sontag. I’m so grateful to have the opportunity to edit and commission other writers’ work and to write book criticism of books that interest me and to have been fiction chair on the NBCC board. But I feel severely off if I focus exclusively on other people’s work, but don’t also make time for getting into the flow of my own fiction, and that influences the care with which I carve out my time exactly to try to perform up to snuff in each of these roles at the right time. I was a litigator for nearly a decade during my formative 20s and trained to bill work—done with harrowing, burning perfectionism—in 6 minute increments; I’m a person who still lives at that level with any form of work always, so even though I last lived that life 14 years ago and there is less pressure on me now—since I’m employed in a very different field and meet other sorts of people—keeping a log of hours of work for which clients could be charged made me particularly attentive to what work takes priority when.

In the end though, the ability to do all this in middle age is mostly the result of two outrageously fortunate things—I have a writer husband with whom I have parity in parenting, and I chose to live six minutes from my solid, generous parents, who enjoy time with their grandchildren and are sympathetic to both my lifelong writerly ambition and the severity of my medical conditions, even though it wasn’t a place conducive to literary community for my husband and me.

JC: Are there short story writers/short stories that influence your work? Or other writers? Do you have a favorite short story collection?

AF: Robert Coover’s experimental short story “Going for a Beer” is an important story for me. Its sentences capture a certain feeling of time rushing forward without our consent or full cognizance and the feeling that our free will is more diminished than we realize. Other influential stories: Charles Yu’s “Standard Loneliness Package” and Rebecca Lee’s “Slatland,” which were also part of Ben Marcus’s incredible anthology New American Stories. Some full collections I love include Laura van den Berg’s I Hold a Wolf by the Ears and Helen Oyeyemi’s What Is Not Yours Is Not Yours. But the authors who most influenced How We Know Our Time Travelers specifically are Anna Kavan, Adolfo Bioy Casares, Marie Ndiaye, Yoko Ogawa, and Julio Cortazar. I did not realize the extent to which Casares’s brilliant novella, Invention of Morel, had burrowed into my subconscious, until after I was done with the collection—I acknowledge the debt via epigraph.

Maybe it sounds quaint, but the collection with which I have the most profound relationship, the one I want someone to read me on my deathbed, is Eleanor Farjeon’s charming and magical children’s collection, The Little Bookroom, which is illustrated by Edward Ardizzonne and dates back to 1955. In terms of influence, there’s a story in there, “Love Birds” that I carry around with me psychologically.

JC: What are you working on now/next?

AF: I’ve been working on a literary surveillance novel. It’s kept me deeply involved since election week 2020, but I can also feel myself reacting against the paranoid creative headspace I had to stay in to finish, and once I send the rewrite to my agent this weekend, I get to start working more seriously on a bildungsroman, perhaps also a love story, set in what feels now like a different country of its own—1980s-1990s Bay Area.

__________________________________

How We Know Our Time Travelers by Anita Felicelli is available from WTAW Press.

Jane Ciabattari

Jane Ciabattari, author of the short story collection Stealing the Fire, is a former National Book Critics Circle president (and current NBCC vice president/events), and a member of the Writers Grotto. Her reviews, interviews and cultural criticism have appeared in NPR, BBC Culture, the New York Times Book Review, the Guardian, Bookforum, Paris Review, the Washington Post, Boston Globe, and the Los Angeles Times, among other publications.