Angela Flournoy on Writing a Polyphonic Novel of Black Female Friendship

Jane Ciabattari Talks to the Author of “The Wilderness”

Angela Flournoy follows her highly honored first novel, The Turner House (2016), with an illuminating polyphonic exploration of the glorious heights and darkest lows of friendships among four women. Her powerful, intimate story spans nearly two decades, from 2008-2027, and incorporates locations from Paris to Harlem to Inglewood. Her intricately detailed scenes embed the reader in the interior and exterior lives of her narrators, evoking a continuous flow of life as they’re living it. Her craft is superb. The dialogue feels authentic. The scenes contain surprises at every turn. There’s something magical about Flournoy’s ability to immerse readers in the universe she has created.

What inspired The Wilderness, this new novel about friendship and Black womanhood? I asked Flournoy. “Ten years ago, when I began thinking about this novel, I was thirty years old, and at the time I lived in New York and spent every moment I could with my girlfriends, who I’d known since freshman year of college,” she explained. “I began to think about—and to worry about—how these friendships might shift as we got older. My mother, who died in 2020, also had a few very close friends, who she’d known for decades, people I grew up calling my aunties. I always admired their relationships. They were the backbone of each other’s lives in this way that felt radical, and worth contemplating in fiction.”

*

Jane Ciabattari: How did you arrive at the title?

Angela Flournoy: Contemporary adult life—not young adult life, but the stretch that plants us in middle age—is akin to a wilderness. Mysterious, with no one clear path, and the need to find your footing as you go.

JC: In a recent Instagram post you write about how you and several junior high school girlfriends had “very big dreams that we took very seriously,” and how you recently asked them to read your audiobook for The Wilderness (and they said yes). How have longtime female friendships like this shaped your life? How have you stayed in touch?

AF: Those two friends, the actor Aja Naomi King, and the actor and writer Ashley Nicole Black, were important to me because we did not go to a school with a large number of Black students, and we often found ourselves the only three in the artistic spaces we gravitated toward—on the dance team, doing theatre, etc. In the years since they have felt like fellow travelers for me, and though we didn’t go to the same universities or always live in the same cities, we rooted for each other and celebrated each other’s victories. Social media makes some of these things easier, of course. Having people in your life who knew different iterations of you is a useful reminder that you never stop having the ability to change or grow.

I wanted this to be a millennial coming-into-middle-age story, and built my characters accordingly.

JC: Your narrative, with its shifting of points of view among four longtime friends, allows for intimacy and drama as well as betrayals and loss as Desiree, Nakia, Monique and January (with Desiree’s estranged sister Danielle mostly on the sidelines) each tell their stories. How did you go about building these characters?

AF: Every character I write begins with a choice—to do something or to refrain from doing something, say—and after the first choice, subsequent decisions must be made, thereby creating someone who feels real on the page. The initial choices for characters in The Wilderness had to do with my various preoccupations at the time, whether it was the rise of “influencer” as a valid career path, or the difficulty of separating from a good-on-paper man. I wanted this to be a millennial coming-into-middle-age story, and built my characters accordingly.

JC: In your opening scene, in 2008, Desiree is with her grandfather Nolan, who had been in Paris while serving during World War II, and has selected an end-of-life option in Switzerland. She accompanies him while he has his last swing through neighborhoods he knows, mostly in the fifth and sixth arrondissements. Does this melancholy trip echo a life experience of your own? Was there travel involved?

AF: I have been interested in the history of African diasporic people in Paris since I took a study abroad course in college nearly twenty years ago called Paris Noir. It was led by Syracuse professor Dr. Janis Mayes, a Diaspora Literatures scholar. In the years since, an excellent walking tour by the same name has cropped up, created by Kévi Donat, and the Centre Pompidou put on a multifaceted “Paris Noir” exhibit this past spring. I’ve traveled to Paris a good amount in the years since that course, and I remain interested in what kind of freedom past generations of Black Americans felt in the city, particularly American GI’s who found themselves there after living under Jim Crow back home.

JC: In a post for Jami Attenberg’s 1000Words this past summer, you mention having a baby and being isolated during COVID, a time in which you “spent the next two years meeting with the same four people, day in and day out, to write fiction alongside each other at a café in Los Angeles.” How have writing friendships like this and others helped shape your work on this novel?

AF: The writers I referred to are Jade Chang, whose novel What a Time to Be Alive comes out this fall, Aja Gabel, whose novel Lightbreakers also comes out this fall, Jean Chen Ho and Xuan Juliana Wang. The best thing, in hindsight, about writing alongside these women was that we did not talk in detail about our works in progress. We all just had a desire to make progress on our second books. Our friendships were deepened by our commitment to the work and to all of the things we learned we had in common outside of being writers. I’m sure making these new connections while working on The Wilderness helped me think deeper about why people become friends in the first place.

JC: “A work of cinema, like a novel, is a collage,” you note in a New York Times profile of director Barry Jenkins. “The finished product is a result of hundreds of moments of cut and paste.” Your conception of this novel is beautiful in its detail. Was the process of writing it like a collage?

AF: The process of writing anything, whether it is an essay or a novel, is like collaging for me. I don’t necessarily start at the beginning; I go wherever feels interesting and urgent, and I move things around until the work makes an intellectual and emotional sense to me, until it has the right movement.

JC: What made you decide to juggle timelines between 2008 to 2027, and to place some scenes out of chronological order for great dramatic effect? How did you manage this complex “threading all of the needles on a structural level, on an emotional and intellectual level”? Did you map it out?

AF: I don’t think about story chronologically; that’s just not how my brain works. I think about emotional beats, and reader payoff, sure, but mostly I think about the best shape for the central concerns of the work. How can the shape of the novel best mimic the feeling of growing into middle age, how can it best reflect what it felt like to have been present for the last 20 years of American life? Of growing closer to certain friends at certain times, and drifting away from others? I asked myself these questions again and again over the years it took to write The Wilderness, and my answer was a prismatic approach. We see each point of view character when we need to see them, at a moment that is important for their trajectory. I’ve heard a few people talk about the book as a kind of novel-in-stories, but as much as each chapter might have satisfying movement on its own, you can’t get a full sense of the thing until you read the whole. That is what makes a novel a novel.

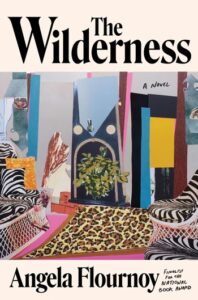

JC: Your cover is a collage by Mickalene Thomas, “Interior: Zebra with Two Chairs and Funky Fur, 2013.” She is the photographer/collagist/painter and “genius with craft” you profiled for the New York Times. How does this work mirror the inner world of The Wilderness?

As much as each chapter might have satisfying movement on its own, you can’t get a full sense of the thing until you read the whole. That is what makes a novel a novel.

AF: In the research process for that profile I had the pleasure of trying to hunt down a picture of every work that Thomas had produced up to that point (2021). Thomas’s interior paintings and collages are less well-known compared to her beautiful, monumental portraits, but they always intrigued me. They invite the viewer into a space that feels intimate yet made for company (they are living rooms, after all), for being together and relaxing. That aspect alone felt apt for The Wilderness, but there’s also the particularities of how the spaces are decorated, and the layering of styles, textures, and time periods as suggested by the collage effect itself.

JC: How have works of visual art, films, other books influenced you during the writing of The Wilderness?

AF: I am a proud maximalist when it comes to things that might add depth to a character’s world, so there is music—from early-aughts club bangers to Bach—literature, film, and TV aplenty in The Wilderness. While writing, I read the Black women writers whose words appear as epigraphs in the book: June Jordan, Toni Cade Bambara, Toni Morrison, Gayl Jones, Audre Lorde, and Wanda Coleman. Some art that stuck with me include the Jack Whitten retrospective at the Hamburger Banhof museum in Berlin, a Beverly Buchanan exhibit at the Brooklyn Museum, Betye Saar exhibits at both LACMA and MoMA, and an exhibit of Matisse’s bronze sculptures at Kunsthaus Zürich.

JC: You capture so many cultural moments in each section of The Wilderness. What sort of research was involved in developing the details, including specifics about your settings, including Harlem, Inglewood, Central Park, Meridian Hill, Montparnesse?

AF: If I wasn’t a writer I’d be a baker, and if I wasn’t a baker I’d maybe be an urban planner. I love cities, and I love learning about the history of their neighborhoods, transportation systems and public spaces. I was fortunate to have a fellowship at the Cullman Center for Writers and Scholars at the New York Public Library when I first started working on this book in 2016, which means I had access to the Maps Division of the Bryant Park location of NYPL. That was immensely useful. I’ve also lived near all of the locations you mention, if only for a few months for some of them, which helped when rendering them in fiction.

JC: Did you have your speculative ending in mind from the beginning (no spoiler here)? How did it evolve?

AF: From the outset I wanted to project into the near-future, to give myself space to think about where our world might be headed. It took longer than I anticipated when I began in 2016 to complete the novel, which means the book ends only a few years beyond our present moment, but the ending I imagined way back then, which had seemed like such a wild departure, became more and more plausible as the years passed by.

JC: What are you working on now/next?

AF: I am finishing up a memoir about motherhood, grief and—unsurprisingly—the history of the places that made me who I am.

__________________________________

The Wilderness by Angela Flournoy is available from Mariner Books, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers.

Jane Ciabattari

Jane Ciabattari, author of the short story collection Stealing the Fire, is a former National Book Critics Circle president (and current NBCC vice president/events), and a member of the Writers Grotto. Her reviews, interviews and cultural criticism have appeared in NPR, BBC Culture, the New York Times Book Review, the Guardian, Bookforum, Paris Review, the Washington Post, Boston Globe, and the Los Angeles Times, among other publications.