Anatomy of a Lifelong Friendship

Ariel Delgado Dixon on What It Means to Find a True Best Friend

One recent winter night, I was careening down a patchy farm lane, behind the wheel of a 16-year-old John Deere buggy reinforced with duct tape and elbow grease. I’d shut away the cows, my last chore. My eyes and nose leaked as I raced into the freezing wind back to the barn, dreaming of a hot shower, a hot meal, the lull of soft sheets. That was when the buggy began to blink. Its bright yellow eyes fluttered, the engine coughed, and after a few jolting yards more, succumbed in the wild dark near the back pastures.

The law of the farm is fixing things, but you can never stay ahead of what is broken. If you can act preemptively, instead of reactively, you are enjoying a fleeting spate of good luck.

I pumped the choke and wiggled the battery wires, eyeballed the gas in the tank. All my usual tricks were proving useless. My time as a dairy farmhand has taught me much, including when to bring in the big guns. So, I fished my cellphone from the front zip of my coveralls and dusted hayseeds from the speaker. I knew who to call, who I always call.

Because K. always knows what to do.

To K., rules are insulting suggestions. To know her is to love her—and to fear her a little, too.

K. is my best friend. She is also a cow whisperer, pastry chef, renegade, and brawler.

We met in high school, where she was known for a raucous laugh and her inability to maintain our prep school dress code, she of the unabashed cleavage. To K., rules are insulting suggestions. To know her is to love her—and to fear her a little, too.

We did not run in the same circles. I was uptight, sequestered, on a nodding basis with some popular kids, but not among them. K. and I have different versions of our first encounter. She says we met in a freshman year Spanish class, when I ratted her out for cheating on a pop quiz. Though I was certainly a goody two-shoes, I maintain that I was not a narc.

My version occurs later, in junior year, when K. sits behind me in our underachievers’ math class. One day, she taps me on the shoulder and offers me 20 dollars to write an essay for her. When I waffle, she offers 40. I tell her I need to think about it, and go home that night to fret a while before declining her offer the next day. When I do, she laughs right in my face. How could I pass up such an easy gig? Ironically, I will go on to write many papers for K., free of charge, but right then I am not ready to see past the veil of law and order that has kept my world neat.

One afternoon soon after, as I wheel my station wagon out of the school lot, I spot K. pacing in front of the student center, face hidden by the hood of her black puffer coat. During this era, she sports a constant cat-eye, bleach-blonde hair, hoop earrings. She’s unmissable, and for whatever reason I stop and ask if she needs a ride.

This is where it begins. A friendship marked by many firsts in quick succession

This is where it begins. A friendship marked by many firsts in quick succession. Strutting down Nassau Street in Princeton, we split a cigarette and I cough egregiously at my first ever inhale, as K. laughs like a maniac. In a barren park near school, we hollow out a menthol cigarette, repack it with weed and tobacco and I blink stupidly through my first high. We take the train into New York to score fake I.D.s and crisscross Manhattan to find our connect. Before the last train home, we sprint to the nearest bar and shove our way to the rail, request two shots of Grey Goose like we know what we’re doing, fresh I.D.s in hand like tickets to be torn. The bartender charges us $40 and doesn’t even ask to see them.

I’m headed to lunch one Thursday when my English teacher asks me to stay behind. A fellow teacher has joined us, a sign this is Official Business, and together they address the changes they’ve witnessed in recent months. The activities that interested me, where I’d positioned myself front and center—the politics of the student newspaper, the melodrama of the literary magazine—have lost their luster, and it shows. I’m writing on my own time more than ever, flush with new sensations and a horizon that’s split open into limitless stimuli. But they can’t know that, or, they don’t ask. Instead, my teacher nearly sheds a tear as she alludes to the ill influence she fears I’ve fallen under.

My face is red, but my defiant streak has blossomed in recent months. I lift my chin and make specific what she is hinting at.

I ask, Is this about K.?

While my teacher pontificates, a presence moves into view at the door, in the square of glass through which the roiling hallway can be glimpsed. It’s K. She gives me a purposeful look then lifts two middle fingers, pumps them in the air. The window is behind the heads of the two teachers trying to serve me a lesson. No one can see her but me. How could I explain it?

In not knowing what I’m doing, I know exactly what I’m doing.

I wait for my teachers to finish their pitch. Then, I go to my friend.

K. is waiting for me, surrounded by doting stoner boys always vying for her attention.

When she sees me, she says, Where the fuck were you?

*

There is a side of K. I catch flashes of sometimes—when she’s angry with her boyfriend, or pissed at her mom. A raw, combustible temper. Sometimes a despair, too. That vital magnetism of hers shrinks. Her spikes go dull. She has experienced much tragedy in her short life, and no amount of vivacious revolt can camouflage it.

Before we became friends, she served two stints at behavioral rehabilitative centers for adolescents, part of the Troubled Teen Industry, or TTI. Wayward youths are stolen away in the night to wilderness treks meant to set them straight, isolate them from the mighty forces of Risky Behavior. Or, they are taken to specialty campuses that range in severity, from the fenced-in compounds of a detention center, to a private estate where group therapy goes hand-in-hand with physics class. Ranks are rampant with abuses, invasions of privacy, reprogramming. A theater in which one must live and relive their worst mistakes and traumas, en route to a finale of healing—a cure you can buy, month by month, totaling in the thousands.

These days, the danger of these institutions is better understood. Online communities have sprouted up, wherein survivors compare notes from stretches at the same facilities, or grievances about predatory counselors. Many survivors experience PTSD, and celebrities like Paris Hilton have come forward to share their experiences. Still, TTI institutions proliferate under ever-shifting names and entities that dodge accountability. Their fuel is abundant: parents often acting in good faith, who feel powerless to correct the dangerous course their children have set upon.

*

A year after high school graduation, K. got into deep trouble and went for another stint at a TTI institution, this time remaining there for almost two years. Communication was strictly limited, but I did receive one email from her, forwarded through her mother.

Hey dude, K. wrote. Like a postcard from summer camp, but I knew she wasn’t lakeside somewhere, learning to bead.

I was in Los Angeles for college. I’d been daring enough to venture cross-country for school, but now I was homesick and lost. I kept searching for a friend like K., who could lead me where I was too afraid to go solo—but there was no one like her. I had to learn for myself.

When K. finally came back to town, somehow the time that passed was of little consequence. We reconvened at our usual spot, on the side-porch of her mom’s place in Jersey.

K. had moved on to another brand of cigarette. She had a million stories from exile.

In one, a girl in her wilderness group known for faking seizures puts on an episode so convincing she accidentally sends herself tumbling down into a ditch. In another, K. makes camp on an embankment that floods overnight, and when she wakes, she is afloat inside her tent, preening in warm, summer water. Once, she almost runs away, making it as far as the road before she reconsiders, returning herself to containment.

Eighteen years later, K. and I have returned to each other again. I see her almost every day. She works on an organic dairy farm in Jersey, driving tractors, birthing calves, milking behemoth land mammals who largely adore her. She is wise, unrelenting, and unafraid of heavy machinery and animal fluid.

Last year, I started working with her. As always, she is unbothered by my questions and hesitancy. If I’m startled by a cow ready to kick, K. offers to step in. When we cross an electrified fenceline, she puts her boot down on the tensile and waits for me to cross first.

*

After I call K. for reinforcements, she comes rumbling up the lane in a Kubota tractor and we hitch the busted buggy to it with an old ratchet strap. It’s my job to sit in the buggy towed behind her, steering blindly as the mechanical innards of the tractor churn a yard from my face. Brake too suddenly, and the ratchet snap will slacken, then pull taut, ricocheting me toward the unrelenting gears. I must trust my own hand on the wheel.

On the last curve, K. turns back to check on me, her headlamp swinging like a bulls-eye lens. I can’t hear her over the roar of machinery, but I trust where we are going. I give her a thumbs-up, and nod inside her beam of light.

______________________________________________

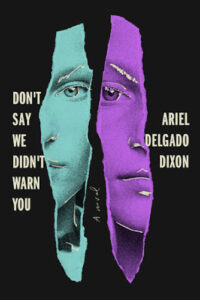

Don’t Say We Didn’t Warn You is available from Random House.

Ariel Delgado Dixon

Ariel Delgado Dixon was born and raised in Trenton, New Jersey. Don't Say We Didn't Warn You is her first novel.