The first time I met Marine for French lessons, she asked me to read a few pages from Le Petit Prince so she could get a sense of my accent and pronunciation. The second time we met, we discussed the vocabulary I’d need should I ever find myself at a foot fetish party—which, incidentally, she had attended the night before. It was on a Wednesday in January, and we were at a coffee shop on Lorimer Street, in Williamsburg.

I was wearing an old sweatshirt and jeans; she was in a fake fur, leather pants, and stilettos that were so high I could only imagine them getting caught in a subway grate, or stepping on someone’s neck. I had arrived a few minutes early for our lesson, and had laid out before me all the tools and flourishes that I thought would make me seem to Marine like a very serious French student: a fresh notebook and a pen; a yellow Larousse dictionary that I would never, ever open. When she rolled in five minutes later, it was in a cloud of smoke, perfume, and mild exasperation. It was one o’clock in the afternoon.

“Wow,” I said, “you really dressed up.”

“Oh, I didn’t go home last night,” she told me, and then smiled sort of quizzically, like it was weird that I had.

It was an insane response—of course I had gone home last night—but it also worked, because a moment later I felt crushingly lame. There’s an explanation for this: Marine is originally from Nice, but spent quite a bit of her twenties in Paris. And like most Parisian women, she has an uncanny ability to make you feel as though you’re about as interesting as a puddle of mud, even when the thing you’ve done is entirely rational and logical, like sleeping in your own bed on a Tuesday night.

I looked down at myself and suddenly noticed how frumpy my jeans were, and how my sweatshirt had a dime-sized coffee stain on it. Desperate to recover, I asked what had kept her out so late.

Crossing her legs, Marine waved her hand in front of her face. “Nothing,” she said. “A foot fetish party.”

I wasn’t sure if I’d misunderstood her—my French was rusty—and so I asked if she could repeat herself. She did, this time adding a bit more detail, and saying the words slowly and clearly, like any good teacher would.

“There were a bunch of men in suits,” she said. “And they took turns licking my toes. It was silly—they looked ridiculous—but they paid me two hundred fifty bucks.”

Now I was genuinely curious. I asked her if this was something she did often.

Marine looked at me like I was crazy. “Absolutely not. A friend invited me.” Then she added, by way of explanation: “She’s Russian.”

I nodded—the way Marine explained it, the whole thing made perfect sense—and then glanced looked down at the notes I’d been taking throughout our conversation.

“Lécher,” I said. “That means ‘to lick’?”

“That’s right!” Marine smiled—she was proud—but then frowned, slightly. “But it’s less ah and more ay.”

“So, like layshay,” I said, trying to mirror the shape of her mouth.

“Perfect!” Her eyes lit up and, buttoning her fur coat, she stood. “Now why don’t you practice that a few more times while I go have a cigarette.”

*

I began studying French in high school. To graduate, we were required to study a language, and because I thought it would be too pointless to learn Latin and too pragmatic to learn Spanish, I landed on French. There was also, I suppose, an element of timing involved in this decision: it was the 90s, and I was gay, which is another way of saying that I had spent a large portion of my childhood obsessing over the musical Les Misérables. Motivations aside, French had quickly become my favorite subject. The teacher—her name was Madame M.—was brass and haughty, and the classroom’s walls were covered with pictures of the Eiffel Tower and chic teenagers eating baguettes. Beyond that, there was something transformative about hearing myself say new, foreign words.

Languages are modes of communication, yes, but they’re also systems of organization and sense-making; they reflect the ethos of a culture, along with its own unique logic. To this end, learning to speak a new language requires that you also learn a new way to be. As a fourteen-year-old who was grappling with my own sexuality—as a child who was often teased for being too flouncy, too excitable, too gay—these brief glimpses of metamorphosis promised a sort of salvation. In Madame M.’s class, I could disappear into conjugations and indirect pronouns and the rough beauty of guttural r’s. I could, in other words, become someone else.

Languages are modes of communication, yes, but they’re also systems of organization and sense-making; they reflect the ethos of a culture, along with its own unique logic.I kept up with my studies through graduation, and then into college, where I declared French as a minor and spent a semester studying abroad in Paris. I will not bore you with the excruciating details of those four months—this is, after all, an essay about Marine. I came back wearing a black, velvet blazer, is all you really need to know. In the decade that followed, however, I slowly—and then very quickly—fell out of practice. Jobs got in the way, along with life, and boyfriends, too; soon, the only time I spoke French was to give directions to foreign tourists, looking for the subway in New York.

None of this necessarily bothered me until the summer of 2015, when I traveled to Rome to visit a childhood friend of mine who had moved there on a whim. At that point, she had lived there illegally for nearly three years, which was enough time for her to find a lover named Marco, learn how to dodge the authorities, and become fluent in Italian. I stayed there for nearly a week, and what I remember most about my visit was the mixture of both awe and envy I felt whenever I heard her argue with a taxi driver, or a waiter, or Marco. Here she was, a stoner from California suddenly transforming into Sophia Loren! On one of my last days there, as I listened to her launch into a tirade of perfectly articulated expletives in the middle of the Piazza Navona, I made a decision: I would find a way to study French again, as soon as I returned to New York.

The problem was that I didn’t know where to look. There were plenty of options—if there’s one thing the French are good at, it’s finding ways to export a sense of lingual superiority—but I also knew that having a good teacher was crucial. While I was studying abroad, I took a medieval art history class from a small Czech woman, and to this day there are certain words in French, particularly those that relate in some way to the construction of gothic cathedrals, that I still pronounce as if I were born in Prague.

Eventually, I decided on a continuing education class that was offered through NYU, where I myself teach. The choice, while logistically and economically sound (I got a discount on tuition because of my association with the university) nevertheless turned out to be a mistake: All of the other students in the class were older women from the Upper West Side. This in itself wasn’t a problem—if you know one thing about me, it’s that older women from the Upper West Side is very much my jam.

Rather, the problem was the instructor: a handsome French man in his late forties over whose attention the older women fiercely competed. Every day they’d come in with stories of a new show they’d seen at Lincoln Center, or a talk they had attended at the Alliance Française. They’d bat their eyes at him and say things like séduisante and sensuelle—words that any sane person might use to describe a massage, or fellatio, instead of a lecture on Sartre—and the instructor would bat his eyes right back.

Meanwhile, whenever I tried to join the conversation, they’d look at me like I was standing between them and lunch. The class lasted six weeks, or maybe eight, though by the end of it I essentially just stopped going. No one wanted me there—the instructor could never remember my name—which, frankly, I understood: a cock block is a cock block, no matter the language you use to describe it.

*

A few months later, I met Marine, and while it’s sort of impossible to paint a picture of her, I’ll do my best to try. To start: She’s in her early thirties. She’s pretty, in that way where if you get close enough you know she’s going to smell a little bit like cigarette smoke, and until she broke it, she rode a little kickboard scooter around town. She’s a surprisingly talented painter, and before she became a language tutor she was a graphic designer and a VJ—a job that, as she describes it, involved making psychedelic videos for music festivals in the Portuguese countryside.

There are certain things about her that are Very French—she refuses to teach more than three lessons a day because life is meant to be lived—and certain things, like her disdain for bureaucracy, that are not. She has two black cats named Faust and Lucifer who she walks around Bushwick on long blue leashes. She believes in chakras, meditation, crystals, and hypnosis; she is also—and on this she swears—occasionally visited by ghosts.

I found her on Craigslist, which as everyone knows is where you go to find cheap bookshelves, bad apartments, and language partners, and after sending a few emails back and forth we arranged a time to meet at that coffee shop on Lorimer Street. I can’t remember if I decided that she would become my regular teacher after our initial meeting, or if it took a lesson on foot fetish vocabulary to seal the deal, but it’s been seven years since then and we’re still meeting once—and sometimes, if I’m lucky, twice—a week.

It feels strange now to refer to her as my “teacher,” because the truth is I’ve come to look at Marine as more of a friend. Over the years together, we have weathered cheating boyfriends, divorces, and green card interviews, which is to say nothing of pandemics and cataclysmic politics. She’s given me pointers on how to train my dog (Marine has a thing with animals), and I’ve coached her on how to dump a few toxic friends. We’ve shared recipes, beers, and cigarettes; we’ve both seen each other cry.

In other words, while we may not swoon over Sartre, we do discuss the messy, complicated business of our lives. And the fluidity of those conversations—the humor, frustration, and occasional argument—have allowed for something that has been absent from my previous studies: not a surrender to French, but rather a merging with it. If as a closeted teenager I found places to hide within the language, now it allows me to express parts of myself I didn’t know were there.

I credit Marine. For all of her eccentricities, the fact is she’s the best French teacher that I’ve ever had. She’s shown me that, in order to speak a language, you have to learn how to let it inhabit you, and, in turn, how to inhabit it. I want to be clear about something here: when I say inhabit, I mean it physically, but also psychologically, and emotionally. When I speak French, I feel the words fill my mouth, forcing my lips forward and my tongue toward the back of my throat; at the same time, I also feel it unlock parts of my brain. Suddenly, there is a new vocabulary with which I am able to describe my world—words that fit my thoughts better than anything I can say in English. There are new verb tenses with which I can explore pockets of time that, before I knew French, I never realized were there.

The fluidity of our conversations have allowed for something that has been absent from my previous studies: not a surrender to French, but rather a merging with it.The sensation is not dissimilar to the one that I’ve come to associate with writing fiction, a practice that often feels like wandering into an unknown country without a reliable translator. Finding your way around a novel requires not that muscle through the sentences with a language you already know, but rather that you finesse your way to a new one. It requires you to imagine a character into a clarity so perfect that you lose sight of where you stop and she begins. Walking down the street, you find that one step is yours, and the next, hers; you stop by a bodega to grab a coffee, and when you speak you half-expect to hear her voice. She fills you with her needs and desires, until—like realizing you suddenly understand the subjonctif—one day they become your own.

To this end, I look at writing fiction as an act of suspended lunacy, and I suppose I could say the same thing about learning French. Both require that you have the capacity not only to understand a multitude of voices, but come to speak them too. This prospect feels especially insane when you consider the peculiar era in which we’re living. At a moment that demands reduction—when we’re told the self is expressed by hot takes and hashtags—learning a language, like the best fiction, requires the patience to expand one’s consciousness. This process is grueling, and by necessity slow; it requires time, and the constant frustration of being confronted by the unknown. Its rewards, though, are priceless: a new way of seeing, hearing, and thinking, along with—at least in my case—the opportunity to take a Parisian cab driver up on his offer to smoke a little weed in the summer of 2019.

I had gone there, to Paris, to research a novel I was writing. I spent most of my days bumming around, doing the things one does when one pretends to be doing research for a novel in Paris—eating four thousand croissants, trying on jaunty scarves, that sort of thing. In the evenings, I would meet friends of mine for dinner. They were Parisians, mostly, but toward the end of my trip I linked up with a handful of New Yorkers who happened to be in town.

On one of these nights, dinner turned into after-dinner drinks, which turned into the always misguided let’s-go-to-a-club-on-the-other-side-of-town. We hailed a taxi, and as my three friends squished into the back seat, I took the spot next to the driver. He was an older gentleman in a wool cap and given how long the trip was, (the club was basically in Belgium), we had plenty of time to talk. I heard about his daughter and the man she was going to marry, along with some lovely descriptions of the town where the driver was raised, which if I’m remembering correctly was up in Normandy. Then, as we crossed over to the Left Bank, the conversation lulled a bit, and when it finally picked up again, he asked me if I’d be interested in buying some weed.

“Like, marijuana?” I said.

The man nodded, then opened the console that divided our two seats. In it, I saw a bag of tidily rolled joints. I thought for a moment, and then because I had drunk at least a bottle of wine and two gin and tonics and was in a mental state in which buying drugs from a Parisian cab driver I had just met made perfect, complete sense, I turned to consult my friends in English. To precisely no one’s surprise, they shared my enthusiasm for the decision.

So, I told the driver that we were in, and as we cruised by the Gare d’Austerlitz we politely haggled over a price, eventually settling on something we both felt reasonable by the time we pulled up to the club. My friends tumbled out of the back seat, and as I watched them sway in the silky Paris night, I reached for my wallet. I counted out bills into two piles on my knees—one for the cab fare, and one for the weed—and after handing them to the driver, he set two joints in the palm of my hand. Behind me, I could hear my friends calling my name, along with the nighttime sounds of the city—the cars and the sirens, the crack of distant laughter.

I turned to get out of the taxi, and as I did, the driver set his hand on my shoulder to stop me.

“Yes?” I asked, worried that I had forgotten something.

“Your French,” he said, and smiled.

“What about it?”

The man shrugged, and gave my shoulder a gentle pat.

“It’s just very good.”

Outside, my friends continued to call my name; we had more drinks to drink, and joints to smoke, and decisions that, in the morning, we would tell ourselves we never should have made. Soon enough, I knew, I would join them. For now, though, I thanked the driver, heartily shaking his hand before he drove away. I watched him for a bit, the cab’s tail lights blurring together until eventually they bled into the rest of the night.

Then, I reached for my phone and called Marine.

_____________________________________________________________

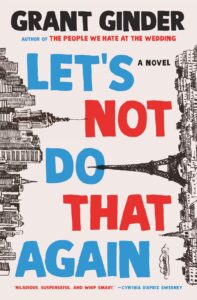

Grant Ginder’s Let’s Not Do That Again is available now via Henry Holt.