An Inside Look at Judith Jones’ First Notes for Julia Child

From the Language of Cooking to Troubles with the Omelette

In May 1960, when Knopf accepted the manuscript for what became Julia Child’s Mastering the Art of French Cooking, Judith Jones—both a respected editor and an avid cook—helped shape the book’s organization and language.

Judith’s editing of the first section of her manuscript was a 19-page document titled “NOTES ON PART I OF FRENCH COOKBOOK.” In preparing it, she likely followed the publishing house’s practice. She first addressed technical matters and then turned to general issues involving style. She went beyond simply making corrections to giving their rationale, enabling her author to understand why a change was needed. For example, Judith cautioned against the use of the impersonal “one” and urged that Julia change it to the more familiar “you.” In Judith’s judgment, “one” was both “mannered” and sounds as though it were a translation from the French “on.” She gave Julia an added reason for the suggested change that likely hit home: “you attract the reader more by addressing him or her directly.”

In working through the manuscript, Judith focused on language, raising issues large and small. Recognizing this cookbook’s innovation was its teaching of French culinary methods, she suggested an important word change: The initial recipe offering instruction for a cooking procedure needed in all cases to be renamed “the master recipe.” Judith preferred that term because it suggested that it is not only important “but the one that establishes a standard.”

As editor, Judith offered directions for making the text more precise. She insisted on page references regarding procedures previously discussed, suggested format changes, and offered language to ensure that the author remain tactful and respectful to readers. But Judith Jones also brought to this book her own advanced culinary knowledge, her love of French food, and her experience as a dedicated home cook in the United States. She retained, as well, her own clear memory of the directions needed by someone just learning to make her way around a kitchen. She used this personal knowledge and experience to call for meaningful changes and additions to the text.

Upon receiving Judith’s “Notes,” Julia must have taken a deep breath before setting to work on its many suggestions.

In various ways, she sought to ensure the future book’s careful consideration in dealing with inexperienced readers. For example, she twice suggested that Julia adopt the word “novice” as a polite way of referring to them. In many cases it seemed like Judith was putting herself in the position of “novice,” imagining herself as a cook working with a recipe for the first time. For example, in dealing with a sauce recipe, she wrote in regard to the pan being used, Julia needed to add “then empty and dry it quickly.” At another point, when encountering tomatoes in a list of ingredients, Judith wrote that Julia needed to state that the tomatoes were to be “skinned or peeled.”

The novices on Judith’s staff at Knopf aided her suggestions: their ignorance of the meaning of herb bouquet led Judith to suggest instead its ingredients—laurel, parsley, and thyme. Judith explained, “cooks are forgetful and I think we should give them this small help here.”

Judith’s knowledge of cooking tools came into play. Copper pots were coming into American use, and that required attention to their potential toxicity. If the lining intended to keep poison from the copper from leaching into food was faulty, Judith wrote, how could one know the danger point? Was it “when the copper begins to show through?”

Later in the report Judith requested Julia discuss plastic bowls as good substitutes for copper ones, as the latter could be expensive and difficult to find. Judith brought Avis into the discussion as she remembered learning from her that Julia had reported that she “had found the American plastic bowl almost as efficient as the French copper one.”

In one of her most interesting comments, Judith wrote a “confession” regarding Julia’s rolled omelette recipe. She had spent much of a Sunday morning “trying to perfect your technique. I even practiced with dried beans outside on the terrace, and managed to use up a whole box of them before I could turn them over in a single group.” Turning to eggs, she failed completely, as her two-egg omelette came out looking like a “fritter.” She wondered if Julia should even offer this omelette method for she did not want the book to “scare beginners.” It should instead “lead the reader by the hand, showing them that even the most difficult is not impossible.” She would ask Bill Koshland, whom she regarded as a good home cook, to give the recipe a try. If he had the same experience with its difficulty, she would suggest Julia add an easier method.

Judith then gave her own method of making an omelette. Although Julia might judge it “a poor tough thing,” Judith liked it because its result was “deliciously soft and tender,” as well as “certainly easier for the novice.” The end result became two omelette recipes in the cookbook, both the relatively easy one to make and the more complicated rolled one. The latter got special care, with four drawings demonstrating its difficult maneuvers.

An issue that would clearly require much work to resolve involved the different measurements used in French and American recipes. Julia and Simca had decided to translate French weight measures into American cups. Judith realized that while this worked in many cases, in dealing with fish, the amounts needed to be in pounds and ounces. Moreover when the ingredient was potatoes, neither would work, because Americans counted potatoes by their quantity.

Judith took care with the illustrations. In one case, she felt there needed to be an additional drawing to go with the recipe for “molded French Pancakes,” as she found the “directions a bit hard to visualize.” She also pointed out that the photo illustrating a particular recipe showed an oval dessert spoon, not the round soup spoon described in the text. No detail was too small to attract Judith’s notice and, if need be, to correct.

As Judith finished the fish chapter, she realized it was lacking a full discussion of mussels. While there was a recipe for moules marinières, the manuscript presented it only as a garnish. Judith wrote, “a fish chapter without a mussels recipe in a French cookbook seems inadequate.” This led Julia and Simca to return to their records to find mussels recipes and develop them for the book; by August 24, Julia put that mutual effort in the mail.

The poultry section of the book raised a number of important issues.

Significant were the different standards of doneness in the U.S. and France. After testing, Judith found the method in the manuscript left the chicken “by American standards . . . slightly underdone.” Julia needed to warn readers of this, as their thermometers would not go as high as they normally did in roasting. After going over Julia’s chicken directions in detail and requesting slight changes, Judith returned to the doneness issue to ask the question, “Is ‘ten to twenty minutes roasting’ really enough?”

Desiring to keep the future book French, Judith rejected Julia’s deletion of a sentence about the French not washing their chicken. Asking for it to be restored, she revealed her interest in conveying its connections to life in France. “Frankly, I like this kind of note because the whole book is so full of the way French do things and I think this kind of detail adds a special flavor.”

As Judith ended her report, she returned to some larger matters, including giving instruction early in the book on clarifying butter, degreasing, and preparing stock in advance from poultry scraps. She closed with the previously expressed need to alter the ingredient amounts or number of portions, because as written, the dishes will not “satisfy American appetites.”

As a polite editor, Judith had framed all her corrections as suggestions.

At moments, Judith’s own likes and dislikes peer out of her “Notes.” Sausages had been one of Judith’s announced interests, and when she turned to recipes that included them, she both commented on the different kinds and asked Julia to specify which one was to be used. Judith held a clear distaste for commercial potato chips. Thus when she saw the term mentioned as a food accompaniment, she feared readers might think of “the American packaged kind, heaven forbid.” At that point, Julia needed to give a cross reference to the recipe for homemade ones.

The single instance when Judith criticized Julia in a direct way was on noting Julia’s negative reference to competing recipes for the “average coq au vin.” Seeing this as an “advertisement for your own book,” Judith asked Julia to delete it. She informed Julia that Knopf would play this part when its staff created the book’s promotional material. The press was working on ways to demonstrate that the instruction in Julia’s book was necessary “to use effectively the other cookbooks readers may have already on their shelves.” Judith also attempted to temper Julia’s exuberance by requesting that she avoid throughout the word “happy,” perhaps using “delicious” for a substitute.

One element in Judith’s report led to extended conflict with Simca. Judith asked Julia to specify, when mentioned in the text, some of the good orange liqueurs available in American stores. Julia’s compliance caused Simca to fight against this insertion. Members of her family were still in the Benedictine business, the liqueur created by her grandfather, and they would be angry at seeing brand names of competing liqueurs in her book. Ultimately, Simca saw the names excised.

Upon receiving Judith’s “Notes,” Julia must have taken a deep breath before setting to work on its many suggestions. One thing is clear from the markings on her copy—Julia recognized the knowledge and skill that Judith brought to her reading of the manuscript. As a polite editor, Judith had framed all her corrections as suggestions. This led Julia to put check marks in the left margin as reminders that she had made the changes Judith sought or had in other ways resolved the issue. Only twice did Julia not make a check, but on both occasions this was because the changes she made were in a manner somewhat different from her editor’s suggestions.

__________________________________

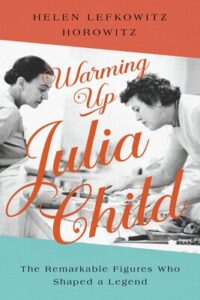

Adapted from Warming Up Julia Child: The Remarkable Figures Who Shaped a Legend by Helen Lefkowitz Horowitz, published by Pegasus Books.

Helen Lefkowitz Horowitz

Helen Lefkowitz Horowitz, Sydenham Clark Parsons Professor of American History and American Studies, emerita, Smith College, is a historian whose work has focused on the cultural history of the U.S. and on culturally important biographical subjects. Honors include the 2003 citation for her book Rereading Sex (Knopf, 2002) as one of three finalists for the Pulitzer Prize in History and the Merle Curti Award given by the Organization of American Historians for the best book in American social or intellectual history. In 2011 she (in conjunction with Patricia Hills) won the W.E. Fischelis Book Award of the Victorian Society of America for John Singer Sargent: Portraits in Praise of Women. Helen is also a well-known emerita professor at Smith College. The college’s large alumnae are unusually loyal to their alma mater, as was Julia Child during her lifetime.