An Expat’s Homebase: How the Iconic Village Voice Bookshop in Paris Launched Lit Mags

Odile Hellier Reflects on the Work of John Strand, Kathy Acker, Ricardo Mosner, and More

As I was working on my project of an Anglo-American bookstore in 1981, I never anticipated the sudden arrival of so many young Americans in Paris, coinciding with the future opening of the Village Voice, and so a stroke of luck for us. Yet there was nothing surprising in this new influx of expatriates from the US. Reminiscing about his youth in 1930s Paris and his joint reading with Hemingway at Beach’s Shakespeare and Company (1937), the English poet Stephen Spender remarked at his Village Voice reading in 1988 that the new wave of Americans had the same economic basis as the massive immigration of the Lost Generation.

In both cases, they could live in Paris on a “far traveling dollar.” Barely worth four francs in 1979, the dollar value rose to ten francs in 1983, given France’s inflationary economy. Sheer happiness for our fledgling bookshop, as it meant more American customers and a larger audience for our readings!

On the other hand, importing books from the States cost more than anticipated, cutting into our inventory resources. Fortunately, the attractiveness of our café steadily brought in the necessary funds to continue to import a wide range of American titles, the distinctive feature of our bookstore.

I first became aware of the growing number of Anglophone expatriates in and around Paris through the discovery of the English-language Paris Passion, a large-format magazine with eye-catching covers. It primarily targeted American expats, providing them with precious information on French ways of life and culture, and, by a happy coincidence, the first issue we carried featured an article called “French Intellectuals and the Left Bank.”

Started in 1980 by Robert Sarner, a young entrepreneurial Toronto journalist, Paris Passion was the forerunner of a flurry of small American literary magazines that popped up in Paris, following the great tradition of the glorious 1920s. Alongside various poetry booklets, literary magazines appeared in the winter of 1984 and ’85, among them Paris Exiles, Frank: An International Journal of Contemporary Writing & Art, and Sphinx: Women’s International Literary Review.

Each was launched at the Village Voice, creating a continuing dialogue between contributors and their readers, coming mostly from the community of American transplants.

Each was launched at the Village Voice, creating a continuing dialogue between contributors and their readers, coming mostly from the community of American transplants.

–Odile Hellier

*

John Strand

The founder of Paris Exiles, John Strand, a young American playwright, clarified its title in his first editorial note, writing that “exile has many shades of meaning of which political exile is only the most visible…exile could be self-imposed, spiritual and artistic.” Whether physical or emotional, the feeling of exile is an experience common to people living away from their familiar environment. This complex theme led Strand to conceive his review as an open forum wherein writers and artists from all countries could meet and exchange their works.

Consistent with his mission, on January 25, 1985, he launched the first issue of Paris Exiles at the Village Voice, along with three emblematic young authors of the eighties: the American iconoclast Kathy Acker, the Soviet dissident Eduard Limonov, and the ’68 French “New Philosopher” Bernard-Henri Lévy.

Kathy Acker cut a dashing figure, sporting her punk haircut, ear piercings, and tattoos on her muscular arms. She looked like an intrepid tomboy, but New York literary circles considered her to be the heir to William Burroughs. Like Burroughs, she was a subversive writer ready to break all taboos and an adept of his Dadaist technique of the “cut-up.”

Acker read an excerpt from her work-in-progress Don Quixote, Which Was a Dream, a conversation between a dog called Nixon and its bitch, Mrs. Nixon. Herein she ignored the politically correct and turned her invective against American politics and its purveyors into the most extravagantly tall stories. The piece was later performed at the American Center, which closed in 1994 after fifty years of showcasing the French-American avant-garde arts.

Another one of Acker’s novels, My Death My Life by Pier Paolo Pasolini, was staged at the Théâtre de la Bastille by the American playwright and stage director Richard Foreman who, at one of Kathy’s readings, described her to us as “the wildest writer going….Originality. Sheer voice. Guts.”

Eduard Limonov, a Soviet dissident, was another writer who loved to provoke a scandal. Like Acker, Limonov was a hellion, even calling himself “the Russian punk.” Taking advantage of the timid stirrings of the perestroika, in 1974 he moved to New York, the long dreamed-of destination of Russian youth. Disenchanted with “the New World,” he then lived in Paris from 1980 to 1991, enjoying fame and a pleasant lifestyle provided by the sale of his books in the US and France.

That same evening of January 25, 1985, Limonov read passages from It’s Me, Eddie (1976) and His Butler’s Story (1981), comical stories based on his picaresque adventures in New York. Looking like a scraggy tomcat with piercing eyes magnified by thick-rimmed glasses, Limonov, the Soviet “refusenik,” had become the pet writer of the Western publishing world.

In the excerpt he chose, the language he used to describe his trysts with Jewish girls was shocking, but strangely enough, did not seem to offend our American audience, so accustomed to the rule of the politically correct back home. In this first month of 1985, the world celebration of Orwell’s classic 1984 was still in the air, a reminder of the propagandist language that continued to prevail in the Soviet Union. The dissident Limonov seemed to embody the aspirations of a whole country to free speech, and his audience gracefully tolerated the extravagant writer’s repeated verbal excesses.

Following these two mavericks, Bernard-Henri Lévy appeared somewhat aloof, certainly not the forthcoming personality we were used to seeing on our TV screens. He was the star of the “Nouveaux Philosophes,” that circle of young, fervent philosophers in vogue in the 1980s who, engaged in a critical reflection on totalitarianism, broke away from the tenets of the Marxist-Leninist as well as Maoist currents of the 1970s.

With his distinctive white shirt casually opened on his chest, Lévy read an excerpt from his first novel, Le diable en tête, translated into English in Paris Exiles. It described Jerusalem, a city close to his heart, appearing here as “the very symbol epitomizing the cosmopolitan city…the only city that preserves in its very stone the impalpable foundation of its origin.”

An eloquent and passionate man in his opinions and ongoing struggle for human rights, he actually spoke very little, seemingly out of place as he addressed an audience not fully aware of his aura in France.

Ricardo Mosner

“To present, as we do, the painters alongside the poets is simply to acknowledge a truth of our time, that the written word is no longer and will never again be superior to the image.” These words of the editor of Paris Exiles were a reference to the other vocation of the review which was to promote the visual arts. Designed by graphic artist Scott Minick, its second issue featured pen and ink drawings by Ricardo Mosner, an Argentine artist exiled in Paris.

On the afternoon of its launch, July 17, 1985, a young man entered the bookshop carrying a large roll of canvas under his arm and a huge bag of paints. He introduced himself as Ricardo Mosner, the artist who was to work on a painting during the event. It was a big surprise to me, but used to the unexpected, I fetched the tacks he needed to stretch his canvas on the one empty wall of the room upstairs where the readings took place. I was a little bit nervous, wondering how Ricardo would be able to paint anything at all, squeezed as he would be between the wall and an anticipated big crowd.

As the place had quickly filled up, a woman yelled out in a high-pitched voice: “An intimate audience, indeed; an inch closer, it would have been adultery,” triggering peals of laughter. Her protest was apparently a Dorothy Parker witticism. This new issue of Paris Exiles introduced the French writer Pierre Guyotat to American readers. He was the author of A Tomb for Five Hundred Thousand Soldiers, a grueling piece denouncing the French army’s acts of torture during the Algerian War which, for a time, had been censored in France.

Pierre Joris, eminent poet and translator, told us of the difficulties he had encountered while translating an extract for Paris Exiles. As the language and syntax were so strange, it read like a dialect. It was a difficult, time-consuming job, and literary magazines were “great devourers of time,” Joris lamented. On the other hand, his “was a work of love,” he admitted, “but also a huge drain on your own creative energy since the time you spend on the magazine you don’t spend on your own work.”

In the meantime, precariously perched on a ladder, Mosner had been splashing colors onto his canvas for an hour and a half; his action painting” performance stopped the minute the reading ended, revealing figures in motion, drinking to life, as celebrated in a tango, all of them reeling under a brandished knife. It was a street art mural on canvas, bursting with energy, movement, and vibrancy.

Named by the artist Serie Tremenda, the title called to mind both “tremendous” enjoyment of life, and “tremors,” perhaps a metaphor for a country known for its vitality, but recently shattered by violent political repression. Hanging over the staircase that connected the two open floors, this work became the silent witness of all our readings and the guardian angel of the bookstore, opening its wings to the world.

Carol Pratl

The first issue of Sphinx: Women’s International Literary Review was launched at the Village Voice on December 7, 1984, the brainchild of Carol Pratl, a young American poet who had moved from Chicago to Paris in the late 1970s, by now speaking fluent French. Though described as a “women’s review,” “Sphinx had no feminist vocation,” Pratl explained that evening. “It was meant to publish male writers and artists beyond the stereotypes found in standard women’s publications.”

Even if she looked like an elf with her braided blond hair right out of Longfellow’s tale of Rapunzel, Carol was a ball of fire, a dynamo who organized literary events and wrote poetry as well as articles on contemporary dance. A student of Russian at the Sorbonne, she attended the lectures of Andrei Sinyavsky, an author censored in Russia and living then in exile in France.

Later on, taking advantage of Gorbachev’s perestroika, Carol made several trips to Moscow and Saint Petersburg (then Leningrad). There, she befriended artists involved in the avant-garde theater movement started in the 1960s as well as dancers, former students of Isadora Duncan, the American choreographer who had revolutionized the art of dance at the turn of the twentieth century. Duncan’s choreographed works continued to be performed underground by her adepts throughout the worst years of the Soviet period.

During her Moscow stays, Carol gathered new information about Duncan’s life and dance creations in the Soviet Union in the 1920s, inspiring her to write a book on Isadora Duncan along with her grandniece, Dorée Duncan. At the same time, acquainted with many writers in the Soviet Union, she embarked on the bold project of gathering female writers together from America, France, and the Soviet Union.

The First International Women’s Conference took place in Paris from January 30 to February 3, 1989, with about forty female writers from these countries. This landmark event included roundtable debates, public appearances, and readings in various venues, including the Village Voice Bookshop. However, as the Canadian writer Nancy Huston observed, these three groups of writers— American, French, and Soviet—voiced very different approaches to feminism and women’s literature, leaving the prospect of a future International Women Writers Forum rather bleak.

David Applefield

David Applefield left his native Boston for Paris in 1984 with the first issue of his newly born literary journal Frank: An International Journal of Contemporary Writing & Art in his suitcase. His was a warm, outgoing personality as he was curious about people and open to innovative ideas.

A cosmopolitan at heart, and feeling at home in his adopted city, he was asked in an interview what it meant to be an expatriate living in our city. David replied: “Krakow, Kiev, Perth, New Jersey, Montreuil, Cotonou, Tripoli. I like street corners in fifty nations, and I have friends in Istanbul, Bamako, Amherst, and feel equally comfortable in a café in Dakar, Paris, or Boston.” For him, Paris was the place where these four corners converged and the starting point for new cosmopolitan adventures.

Given the international vocation of Frank, a special section in each issue, called “Foreign Dossier,” was dedicated to a chosen country’s cultures and literatures. A few examples are “The Philippines” (1987), “Pakistani Writing” (1988), “Contemporary Chinese Poetry” (1990), and “Anglophone Writing in Paris Today! Updating the Myth.”

In the summer of 1985, Applefield launched the fourth issue of his magazine, dedicated to Edouard Roditi, the highly respected senior member of the Anglophone community in Paris, at the Village Voice. He introduced him to us as the author of art essays, adding that Roditi was fluent in more than eight languages. Of Turkish Sephardic Jewish origin, Roditi was raised in France, educated in England and the United States, and “could boast of an address book containing 613 entries—like the Talmud,” he said with a big smile.

Applefield had also invited the French poet Alain Bosquet to participate in this homage. The two men met in Berlin in 1948 at the start of the Cold War. Bosquet was part of the Allied Control Commissions while Roditi was working as a translator at the Nuremberg trials. Yet it was their love of literature that cemented their friendship.

On July 4, 1985, he introduced his friend Roditi as “a self-appointed ambassador of every possible culture to every other possible culture.” Invited to recall an event that had marked his life, Roditi spoke of a particular moment in London in the 1930s. He had just turned twenty and was writing surrealist poetry, but the political and social context created by the Great Depression of 1929 was a matter of concern to him.

He happened to befriend a certain Eric Blair: they were both enamored by literature and had a shared empathy for the down-and-outs. “We would take walks,” Roditi reminisced,

and I remember a particular night at Trafalgar Square: homeless men were gathered together sleeping outside in the cold. Sometime later, I happened to read a book by a George Orwell, A Clergyman’s Daughter, and, stunned, I realized that one of its scenes was precisely the one my friend and I had witnessed together. Eric Blair was none other than George Orwell.

Another great admirer and close acquaintance of Roditi was Michael Neal, our dear associate at the Village Voice and a “bibliomaniac.” He passionately read and reread Orwell, his hero. At Roditi’s death, Michael was entrusted with this friend’s papers and memoirs.

Jim Haynes

Handshake Editions was a title that fully reflected the personality of its editor—friendly, open, and a most popular figure in the American expat community in Paris. Jim’s background included the cultural and sexual revolution of the 1960s in Edinburgh, where he owned the Paperback Bookshop and staged avant-garde plays at his famous Traverse Theatre.

On November 23, 2005, Haynes arrived at the bookshop with his Scottish friend, John Calder, the main publisher of Beckett in Britain, to share memories of the prestigious writers they had invited to participate in the first Edinburgh International Writers’ Conference back in 1962. Over the following fifty years, they attended the annual Edinburgh Festival, still organizing literary events, never missing a single season.

Haynes came from the wide-open spaces of North and South America and had lived in many other countries, never actually stepping out of the sixties. He taught Media and Sexual Politics at the University of Vincennes, an offshoot of the 1968 student protest movement.

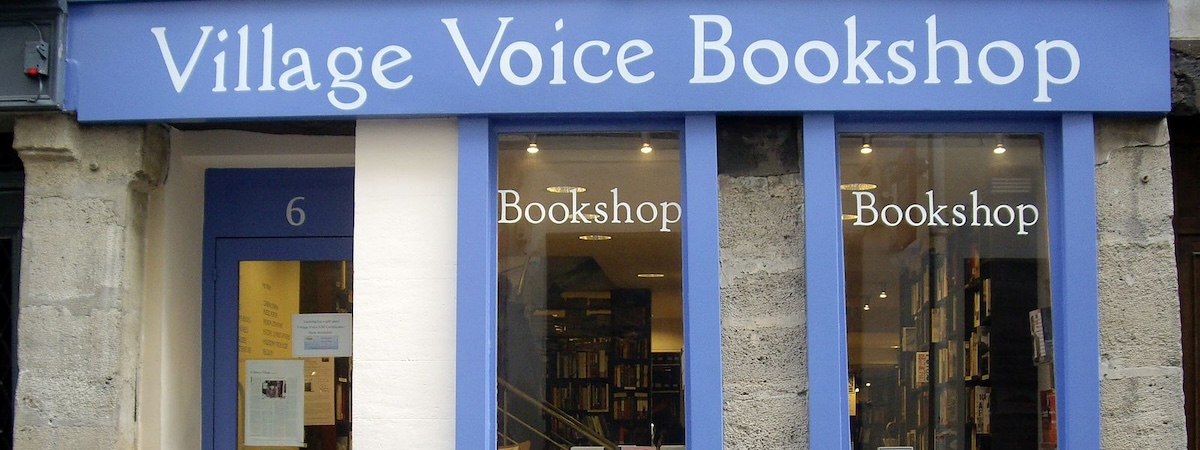

Hearing about the Village Voice Bookshop, a name redolent of the turbulent New York scene, he appeared at the door one day and offered his help. Soon, the store became one of his favorite spots to hobnob with his friends from around the world—all writers and artists—a blessing for an emerging bookstore.

His catalogue of Handshake Editions, a small kitchen-table literary publication, as he called it, listed forty titles that resonated with the free spirit of the time: Workers of the World, Unite and Stop Working (Jim Haynes), Weird Fucks (Lynne Tillman), and In Praise of Henry: A Homage to Henry Miller (Jim Haynes). However, what sparked Jim’s ongoing popularity in the American community here and just about everywhere were his traditional Sunday dinners in his fourteenth arrondissement atelier, once Henry Miller’s neighborhood.

This venue was a beehive of comings and goings: artistic activities with video screenings, photo shows, and a real base in Paris for people to meet, exchange views, cook, and share meals. The two-story studio was often too small and too crowded, so the patio with its colorful flowerbeds and shady trees soon became the perfect Left Bank setting for a budding romance.

Sunday dinners “Chez Jim” have been featured in dozens of international articles, and his aptly named autobiography, Thanks for Coming, is a who’s who of the guests who at one time or another attended his weekly “happenings” over the years: John Lennon, Yoko Ono, Germaine Greer, Mick Jagger, and other stars. What a time we had!

______________________________

Village Voices: A Memoir of the Village Voices Bookshop, Paris, 1982-2012 by Odile Hellier is available via Seven Stories Press.

Odile Hellier

Odile Hellier was born in the South of France during World War II and raised in the two different regions of Lorraine, near the German border still haunted by past wars, and Brittany fronting the Atlantic Ocean. After advanced studies in Russian language and literature she taught in high school for two years, she decided to broaden her scope and work in world organizations. During the fall of 1968, Hellier enrolled in a professional school in Paris that trained translators and interpreters in international relations. Hellier is the founder and owner of the Village Voice Bookshop—a hub of Anglophone literary life and culture that operated in the heart of Saint-Germain-des-Prés in Paris for over thirty years. Village Voices is Hellier’s archival project and personal memoir.